Binondo through the eyes of its people

The heart of Binondo has always been its people. In this dense part of Manila, multiple generations of Filipino-Chinese have carved out homes and livelihoods. Its main thoroughfares are laden with long-standing teahouses, hawker-style stalls, and souvenir shops—mostly manned by those who have seen the district evolve over time.

There are those who see it as an experience of classic Manila, a captivating place rich with layers of history. There are some who see Bindondo as a cultural trend to ride on. But however fleeting one’s relationship with Binondo is, each plays an essential role in the district’s survival.

Young STAR talked to passersby, shop owners, vendors, and workers in the world’s oldest Chinatown to learn what Binondo means to them.

A gastronomic stop for the young

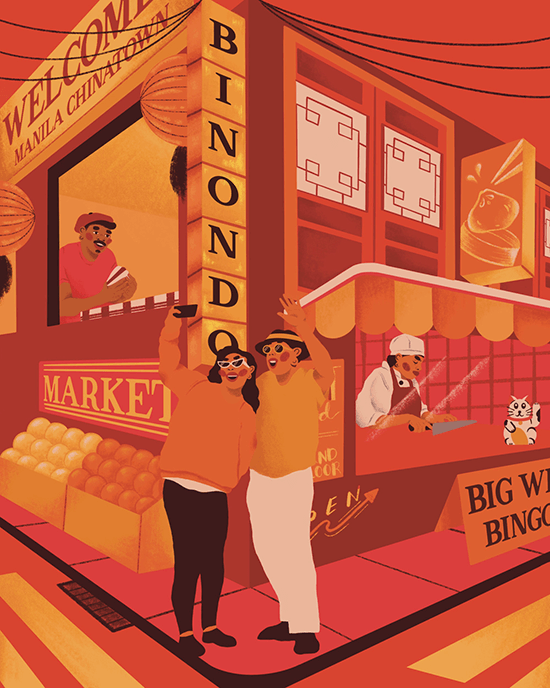

Binondo’s eclectic food scene is a commune of its own, where connections are traded in the form of dim sum, hand-pulled noodles, hopia, and clay pot rice. I found Lara and Charm taking photos in front of what’s considered to be the longest-standing fast food in Binondo. Its first floor is visibly filled with people chattering, a long stainless steel counter and worn-out menu boards behind them. Customers would go down the stairs to the fireman’s coffee shop every now and then.

The sprawling district of Binondo remains vibrant because of the people that make up its ecosystem.

“Nagkayayaan sa office; marami pala [kaming] may gusto mag-food trip dito,” Lara shared. “Meron napanood yung isa naming officemate na TikTok. Rating different food spots. ‘Yun ‘yung naging itinerary namin.”

A few weeks leading up to the country’s first lockdown, I remember planning to spend Chinese New Year at Ongpin, eager for cups of kiampong rice and the sight of locals welcoming the new year. Then precautionary measures had to be taken, and crowded places were no longer an option. While cooped up, I dreamt of steamy hakaw paired with their specialty rice, and the kikiam that my mom brings home as pasalubong, which she says is a Chinatown special. When restrictions loosened, my first agenda was to visit the same fast food place where I found Lara and Charm.

Families found outside home

Ian, who works as a waiter in a popular Chinese deli along the streets of Ongpin, has turned Brenda’s pushcart into his go-to merienda place. “Pa-lista lang, Ate Brenda,” and in exchange, he’d get instant coffee packs and noodles. Working in Binondo for half a decade already, Ian and Brenda have become a family forged and bound by the ins and outs of the district. You’ll see it in the way he’s propped and seated behind the modest pushcart while Brenda serves her customers in front.

“Okay dito sa Binondo. Marami kang makukuhang ideya. Makakaisip ka ng mga bagong diskarte,” says Ian. Being exposed to the district’s rich commerce, it’s easy to take cues from the Filipino-Chinese community’s business-inclined roots. Ian doesn’t see himself leaving Binondo anytime soon and takes pride in being part of a place that creates jobs, but admits, “Sumasabay lang din ako sa daloy kung saan okay.”

His fondest memory of Binondo is when streets are abuzz with people during holidays like Chinese New Year. While the number of people is not as much as Nazareno’s Traslacion, Ian likens it to the Mass procession, citing how it can be difficult to navigate through the kind of crowd Binondo attracts during peak season.

There are also establishments where the passage of time hasn’t been the kindest. But ultimately, all these have shaped Binondo as we know it.

Past its prime years

For Manang Digma, the peak of Binondo was in the early ’80s. Divisoria wasn’t as established as it is now, and people would flock to buy the freshest fruits from her two-lot store. Her shop had oranges and dragon fruits imported from abroad. Back then, her products were known to be rare finds, so it was easy to fill their cash registers to the brim.

She now laments how the district has changed. She recounts how it’s the smell of castañas in the air that brings her back to Chinatown’s prime years—how the streets were jam-packed and you could find bills or pieces of jewelry lying on the pavement because that’s how big of a crowd it used to pull in. She’s been here for 36 years, and now her kids have graduated and her store has been left behind by time.

“Pero kahit ganun, mas gusto ko pa rin dito. Dami mong nakikitang tao. Maraming pwede makausap. Masaya.” Digma says the pandemic gave her a taste of what it is to be away from Binondo, and while her sales have dwindled, she chooses to stay.

The sprawling district of Binondo remains vibrant because of the people that make up its ecosystem. Visitors flock for the district’s cultural experience, while teahouses and stalls—symbols of resilience even amidst economic restarts—thrive and remain reliant on patrons and the influx of tourists and passers-by. There are also establishments where the passage of time hasn’t been the kindest. But ultimately, all these have shaped Binondo as we know it.