Elemental inquiries

Fire, water, wind, earth.

Corrosion may come from nature.

But corruption comes from man.

For Poklong Anading, a Manila-based artist who intermingles his interest in travel with the way nature permutates the human world (and vice versa), the diving world of Davao del Oro, where he originally took up his Lubi Art Residency Program, offered a plethora of new connections. Working with dive master Iñigo Taojo of Davao Gulf Divers and local marine biologists, Anading did dives to recover trash from the seabed (“Every dive is a cleanup dive”), but it also led him to “resurface” materials highlighting the interaction of man and nature in his show “lumalalim sa kababawan, lumulutang sa kalaliman (deep in the shadows, afloat in the depths),” now on view at Silverlens Gallery.

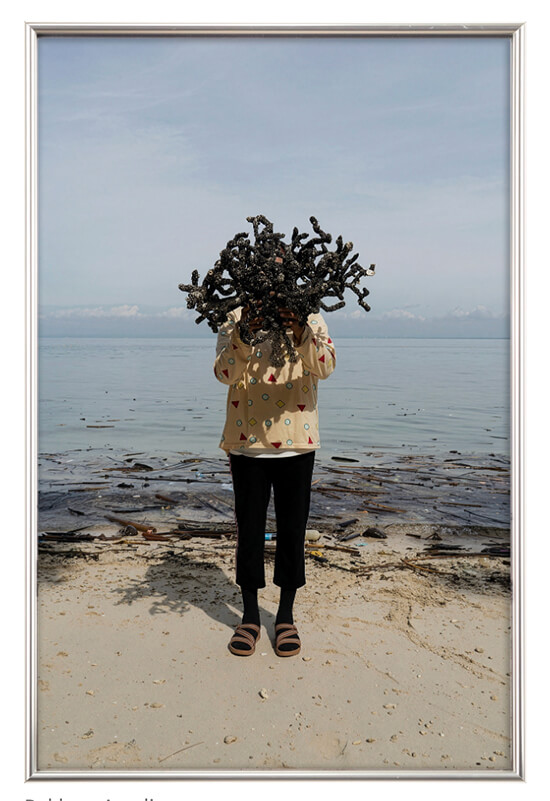

Anading started his creative journey as a photographer, but now adds found-object installations, such as the reimagined coral configurations and massive “ghost net” constructions taking up the bulk of the exhibit. His forays with divers and volunteers in Davao del Oro led to intertwining nature and discarded human debris, such as the wire-wound figures and barrier nets at the gallery entrance.

His work is partly a theoretical reflection on how we consume, and what consumes us, as well as an attempt to turn such debris into something that further lives on in the world. “Whenever I see something like plastic, I think of consumption, buying things. And I ask: who is responsible?” he says in a walkthrough. “When we put trash in a bin, it only stays there so long; it travels much more than us. It collapses into microplastic, with small amounts even entering our bodies.”

He points to a wall piece crafted from wire interwoven with flecks of plastic packaging: a “Fibonacci spiral” suggesting the whirling of nature in outward ripples. The floor-to-ceiling “ghost net” itself was recovered from a diving site: a huge net used to catch fish and later kept in place to keep floating garbage from washing onto shore, it became intertwined with algae and barnacles, almost like a sunken pirate ship threatening the local coral habitat. Nature and man had combined to create something monstrous. But also bearing signs of life. Anading “rescued” this abandoned net to transfer its purpose into art as a “synthetic coral,” also serving as an “homage” to the life forms it has disrupted.

He was at Silverlens for a talk staged by the gallery and the Wildlife Conservation Society, “Deep in the Shallows: Art and Ecology,” along with Kate Lim, country director of the Wildlife Conservation Society in the Philippines and part-time assistant professor at UP School of Archaeology; and Isola Tong, a transpinay artist-architect, researcher, creative organizer and educator who is currently an assistant professor in the Department of Art Studies, UP Diliman.

The talk wasn’t an ecological treatise, per se; rather an engagement from two other perspectives on what forms the basis of our relationship with nature.

Anading had this epiphany, seeing these vast coral walls intertwined with the ghost nets along with mandmade waste: “There’s a whole story you can see in this,” says the artist. “At the same time, it’s growing marine life, with small larvae, so it becomes a habitat for them as well. But they’re both lost, because it’s not stable. And corals are not really plants, they’re animals.” Like us. Trapped in some horrible Cronenberg morph with nature.

But that binary construction of the problem actually is the problem.

“I’m fascinated with the nets, how it’s tangled with the corals,” says Tong, who first did studies in the American southwest on how fire shapes our environment. “I use the framework of tranticology (viewing the world from a trans, non-binary perspective). It’s not about gender, it’s about the process of us being entangled with the ecosystem, how our bodies, as things, are effected by the environment.”

Tong says the piece shows how “private property was translated to the ocean, how non-human lives reacted to it, but weren’t able to form fully because they latched onto this fragile mesh, and now their bodies became part of this plastic mesh.”

“You are part of the system,” adds Anading. “What I noticed with these communities that are directly affected by these practices is that most of them don’t know how to swim. They don’t have time to do that. They are tied up with work.” They don’t have time to appreciate the beautiful surroundings, or see it as a leisure option. “It’s all trabaho.”

Those most threatened by waste are most disconnected from their own environment. No luxury of contemplating the issue of eco-consciousness.

Lim, who notes that 80 percent of our coral reefs right now in the Philippines are threatened by climate change and anthropogenic attacks, says the project with Silverlens at least takes the message to the community level.

“For me, it’s as simple as food,” says Lim. “Making the connection between people’s daily actions and their food source, which is the sea. (The fisherfolk) still earn on a daily basis. So the concept of ‘sustainability’ is far-fetched. They can really only think about today, on how to survive.

“What the ghost net symbolizes, it’s not art for art’s sake, it’s a good story to tell: a good mix of how conservation can cut across the communities, through the people who helped him put it together.”

Anading’s project did employ many local people in fishing areas to help meticulously wrap and construct his ghost net and other sculptures; so there’s a direct economic impact.

Will an exhibit at Silverlens actually change the practices at any level on the ground? That remains to be seen.

“We have to think outside of the box, do collaborations, art,” argues Lim. “Because we now have unpredictable nature patterns. We need to challenge ourselves to create something new.”

* * *

“Lumalalim sa kababawan, lumulutang sa kalaliman (deep in the shadows, afloat in the depths)” is now on view at Silverlens Gallery, 2263 Don Chino Roces Ave. Ext. Visit silverlensgalleries.com. Contact inquiry@silverlensgalleries.com.