The Riddle of the Braille

"Braille for the Seeing” is a mischievous little show. Imagine a photography exhibition that boycotts most of our beloved assumptions about photography. It eschews representation for residue. The documentary, the descriptive, and the diaristic—all nostalgia-laden—are here either abandoned or offset by the deadpan cleverness of conceptual games.

The group show with 13 artists opened last Nov. 7 at the Bulwagang Roberto Chabet in the Cultural Center of the Philippines complex. Teo Esguerra and Gerome Soriano, the initiators of the project, envisioned the show as a counterpoint to digitalization. Photography may lend itself too easily to virtual screens but here, Soriano writes, it “evolves into different sculptural, physical, and material forms” that invite multi-sensory engagement.

These gestures are defined by a risky curiosity, but they also display a bookish grasp of photography discourse and the medium’s vernacular uses. There is a nod to the social gravitas imbued in the class picture, the family portrait, the street photograph, and the still life — but you’d expect all this seriousness to be undone at any moment by a joke and a wink.

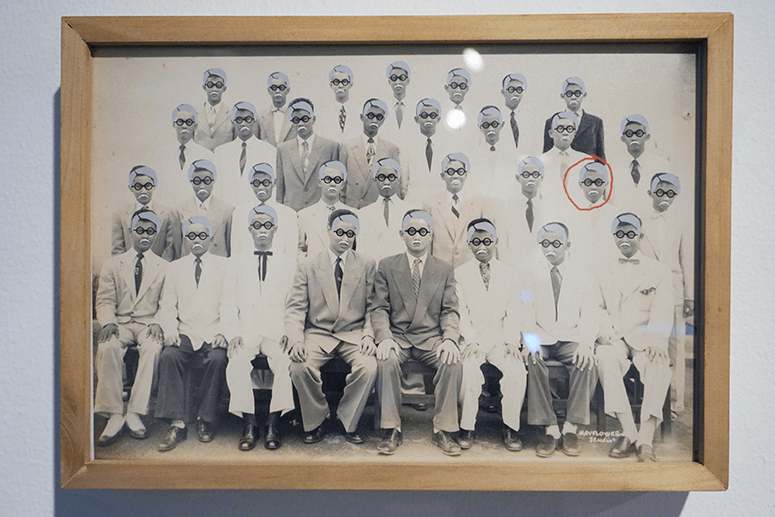

While the installation of the works is straightforward enough, I can’t help but sense that hidden here and there are aliases, jabs, and secrets. On one side of the room is a graying class picture; on the other side is the same photo with glasses and mustache scribbled over faces. The artist is Angel Flores, who is not an actual artist but a fictitious expat character made up by Roberto Chabet. Having been the most insistent enabler of conceptual thinking in these shores, Chabet was a mentor to a number of artists here and the same man from which this gallery gets its name. Frustratingly, however, this curious piece of history is delivered like an inside joke, because of the exhibition’s strange refusal to contextualize the ruse behind the alias.

With its haphazard references and cryptic homages, conceptual art may have something in common with photography as we know it. On the surface, they seem deceptively frank, but when we can’t pick up on the references, this familiarity becomes the very source of its opacity.

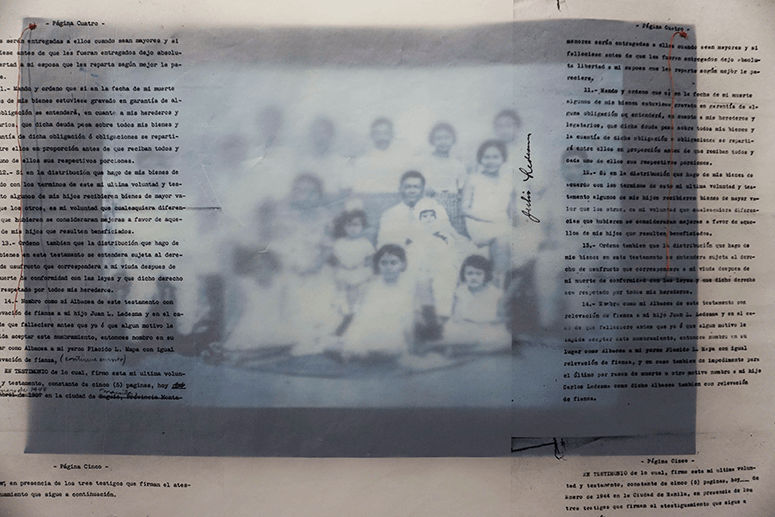

Angela Silva’s piece “Hacienda La Fortuna” manages this tense and delicate dynamic. Cyanotype prints of family photographs hang behind vellum paper, on which is printed two versions of a legal document written in Spanish. There is a reticence to the piece that thwarts total revelation. When I speak with Silva, she tells me that the articles relay the origins of her mother’s dynastic family; the document is a will drafted by the patriarch. Photography, as social rite and instrument for memorial, is charged with fact and intimacy. But as I peer through vellum and a foreign language, property becomes newly inscrutable and fragile, prone to reckless handling.

If Silva’s text is impassive, Gary-Ross Pastrana’s “Fieldnotes 1-10” rambles on and thinks out loud. He ruminates on silver, gelatin, light, exposure, and slightly burning someone’s skin. It’s one of the most amusing pieces in the exhibition. His musings stop us from seeing Rhaz Oriente’s blurred irises as a preoccupation with pure form, but a conceptualist’s fascination with riddles and process.

Touch and contact, the indexical quality of photography, is reconstituted in Poklong Anading’s interactive work. We drag our finger on a screen to uncover — what are they? Painted nails? A set of other index fingers?

These gestures carry a childlike earnestness and mischief. Reading Pastrana’s notes is like watching a child take apart a toy to see what essence could be found among the flayed and glinting parts.

But perhaps the trick and the magic is in putting it back together.

- Poklong Anading’s Untitled (Dwelling). Photo by Alvin Zafra.png)

Touch and contact, the indexical quality of photography, is reconstituted in Poklong Anading’s interactive work. We drag our finger on a screen to uncover—what are they? Painted nails? A set of other index fingers?

Soriano’s tiled mirrors, defiantly kitschy on a hanging cardboard contraption, show our reflection in fragments and multiples—a wildly dizzying, Instagrammable portrait.

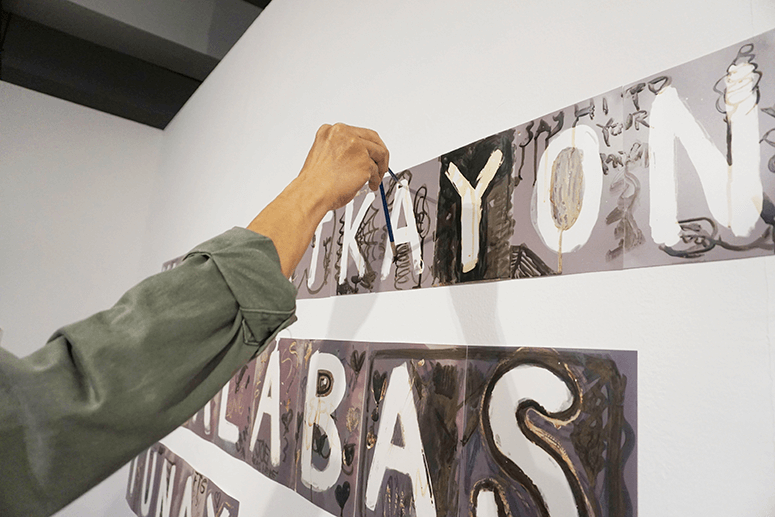

These works recruit the viewer as fellow image-maker and the idea is pushed to its snapping point with Esguerra’s interactive work. In “Permanence,” the artist “strips down the darkroom printing process to its bare minimum.” The audience takes up the brush and applies chemicals on wall-mounted photo paper. There’s something in the gesture that feels illicit and democratic, like writing on public walls, but the resulting work can’t seem to achieve conceptual coherence. There is a joining of idiosyncrasy and commentary, which then appears a little too forced. Photography is stripped down, taken apart, but it struggles to remake itself into a compelling whole.

“Braille for the Seeing,” as a whole, wants to re-imagine photography by flaying its parts. Here is the index, the residue, the trace, gathered through a video, an album or, as in Jan Sunday’s “Flag of Our Mothers,” a beautiful jagged print on flowing satin. The parts do come together but, cut off from larger wholes, at times the pieces seem too immersed in their own internal monologue to have the energy to sustain a spirited conversation with the others. Perhaps this speaks to the curation and how it might benefit from including more than one work from the artists’ oeuvre.

At best, though, the exhibition is a nudge to shift our ways of sensing. We expect high resolution, but Stephanie Syjuco gives us an elaborate approximation. We expect a clear image, but what we get is a finger on top of another finger.

* * *

“Braille for the Seeing” is on view until Dec. 10 at the Bulwagang Roberto Chabet, 3F Tanghalang Ignacio Gimenez, in the CCP Complex.