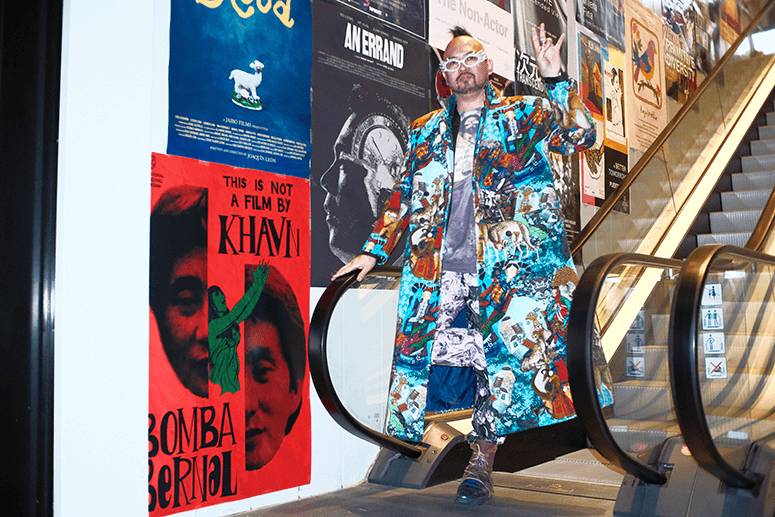

At Rotterdam, Khavn resurrects the spirit of Ishmael Bernal the critic

“It feels like somewhere in the liminal sweet spot between a reunion of ghosts and a lab for generating new cousins,” says Khavn about returning to the 2025 International Film Festival Rotterdam, where he screened his latest film Bomba Bernal.

This was after last year’s Rotterdam entry Makbetamaximus: Theater of Destruction, an unhinged reimagining of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, and after the screening of Bomba Bernal’s extremely rough monochromatic silent cut during the nonstop concert of his band, The Brockas, at the Jihlava International Film Festival in October 2022.

“This unofficial Philippine barangay in Holland has been the supernatural childbirth center for 50-something of my films (beginning) 20 years ago with The Family That Eats Soil (2005) and B-movies,” he continues.

Like its title warrants, Bomba Bernal functions as the Filipino avant-garde director’s ode to Ishmael Bernal, among the country’s National Artists for cinema, and his formative critique of bomba, a Filipino film genre known for relying on superfluous use of softcore and hardcore pornography. The bomba cinema was at its peak in the late 1960s and is gaining resurgence through a constant supply of erotic, haphazard titles from local streaming platform Vivamax.

Bernal’s essays on the genre—which served as the film’s main text, alongside the synopsis of the first yet lost bomba film Uhaw—are collected in a book aptly titled Bomba, published by Everything’s Fine as part of its series, Required Readings. Divided into sections, the 69-minute motion picture truncates, reconfigures, and regurgitates these essays, including a fictitious interview with a bomba star, spiked with Furan Guillermo’s propulsive editing and sound design, to forge a material that operates as part film essay, part archival work, part historical saga, and part critique mining an essential period in Philippine cinema. Past this, a clone of Bernal’s voice is featured in the movie, alongside Khavn and producer Achinette Villamor.

The Filipino filmmaker discusses his foray into bomba cinema, artificial intelligence, and his latest film ‘Bomba Bernal.’

For the film’s visual paraphernalia, Khavn chiefly repurposed the private archive of Daniel Palisa, a frequent collaborator who worked on the prosthetics and special effects of several of his films, the likes of Balangiga: Howling Wilderness, Ang Napakaigsing Buhay ng Alipato, and Makamisa: Phantasm of Revenge. “During the pandemic, he shared with me his bombastic hard drive and the rest is history,” he says.

Hence the torrent of images, colored or otherwise: a body caressing another suffused with heat, sweat and smoke; horses onscreen suggesting sexual urge; a topless woman making her way through a mud paddy; the incessant use of extreme close-ups; a naked body suddenly turning into a corpse; sex by the beach, in the woods, in a nightclub, in bed; and all sorts of voyeuristic gaze.

Here, Khavn discusses his foray into bomba cinema, artificial intelligence, and Bernal the critic. The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

YOUNG STAR: After working on National Anarchist: Lino Brocka, did you feel like making Bomba Bernal was only fitting? I read these films as a diptych, if not spiritually linked.

KHAVN: After Brocka, I really wanted to shake the ghost of his contemporary, Bernal. (That’s also why the third album of The Brockas was titled Manila By Night (2023); and there's Bernal Scotch, the English single from our 4th album Masaker about Bernal’s lost film Scotch on the Rocks to Remember, Black Coffee to Forget.)

Of course, I didn’t want to repeat myself by (not so) simply reworking footage from Bernal’s filmography. I wanted to do something else, which was to use Bernal’s film writing specifically on the bomba genre as the main thread and Frankenstein the footage from existing bomba flicks.

Everything is linked. It’s more akin to the delicious toxic longganisa than to any other mystical sausage. You cut off the navels and you forget that they were connected in the first place. The linker is what makes life delicious. My filmography is a polyptych. You can definitely include Nitrate: To the Ghosts of the 75 Lost Philippine Silent Films (1912-1933)—which also premiered in Rotterdam 2023—in the mix.

The screenplay is chiefly based on Ishmael Bernal’s seminal essays on bomba films. Can you say that the writing is easier this time around, since there is an existing text?

I’m easy as Monday morning. Life is what you see it. The actual writing of words is just one aspect of filmmaking. You can even do away with it and still come up with a great film. Aside from Bernal’s text, I also used the synopsis of the first bomba film Uhaw, which unfortunately is lost. (The poster for Bomba Bernal by our 16-year-old daughter Charlie Sage is also inspired by the Uhaw poster.)

The Filipino audience is fairly familiar with Bernal the filmmaker, but what is it with Bernal the critic that you think deserves closer attention and interrogation?

The filmmaker-critic combo is not common in the Philippines. I would have loved to read the autobiographies of Lino Brocka, Manuel Conde, et al but unfortunately these are all imaginary.

Bernal plays the narrator in the film. How were you able to simulate his voice? Did artificial intelligence have to do with it? This might sound cheeky, but do you consider AI as art?

We resurrected Bernal’s voice through AI voice cloning. AI is another tool for artmaking, like paint and a brush, like the piano and the drums, like the camera and your phone. It’s what the artist does with it that makes it art. I originally wanted to find a voice talent to mimic Bernal’s voice but I couldn’t find the right one. Thank God the technology caught up with the project.

One thing that really stands out in the film is the sound work. How did you go about it with sound designer Furan Guillermo?

It’s inspired by the AM radio reporters where the music abruptly cuts when the DJ is talking and instantly comes back as soon as he stops talking. In the same audio planet as a rotating door in Hotel Godard. Needless to say, Furan’s editing and sound work deserve an Urian Grammy.

How would you locate Bomba Bernal in your work as arguably the father of Filipino digital filmmaking, as well as your recent foray into celluloid and silent movies, like in Makamisa: Phantasm of Revenge (2024), National Anarchist: Lino Brocka (2023), and Nitrate: To the Ghosts of the 75 Lost Philippine Silent Films (1912-1933) (2023)? Where does this fixation for the latter stem from?

Almost everything is digital now. The celluloid-digital debate has been moot for some time. Cinema is cinema. My love for film history beginning with the silents has led me to this sexy realm of found footage. Ang hindi lumingon sa pinanggalingan ay hindi makararating sa paroroonan. Or will suffer from a stiff neck.

Like in National Anarchist: Lino Brocka, you also wrote an original song for this film called Bomba Burlesk. What was that process like? Could we expect more songs like this from your future films?

After the found instrumental music of Pinoy Funk, Pinoy Surf, and Pinoy Cha-cha courtesy of the late Nestor Vera-Cruz of Yesteryear Music Gallery, I wanted a fun vocal track at the end credits. The first verse of the song Bomba Burlesk (“Divina Valencia, Stella Suarez, nagbuburles”) is actually an existing parody of A Hard Day’s Night from the time The Beatles had a concert in the Rizal Memorial Football Stadium circa 1966. Then I developed it into a full song last month. I’ve been writing songs for my films since the late ’90s. Check out Ruined Heart, Katurog Na, Alipato, and the album This Is Not A Film By Khavn on Spotify. Music is film, but that’s another essay.

Are there any great Filipino directors that you’re still hoping to make a film about?

No. Still have to focus on our seven-and-a-half feature films in post-production limbo.