Rizal: His loves, heartaches, heartbreaks

If there is any single Filipino hero who knew most keenly about love and heartbreak in our sad republic, that would be Jose Rizal.

In 1890, he was at his most desperate, in the fight of his life. He would receive news of his beloved Leonor Rivera’s impending arranged marriage to the English railroad engineer, Charles Kipping. It was the unhappy consequence of the girl’s mother intercepting Rizal’s letters for years. That particular news made Rizal break down in tears.

As the last bitter pill to swallow, the rent on the family’s vast Laguna farms—part of the Dominican estate—had been raised to outrageous levels by the friars, and Rizal had advised his father not to pay it. They had fought a long, bitter court battle and lost. The Rizals were thrown out of their family home, Francisco and Paciano sent into exile, while those who remained in Calamba faced persecution. As a result, Jose Rizal’s tenuous financial lifeline, a meager allowance that was always sent late, had vanished.

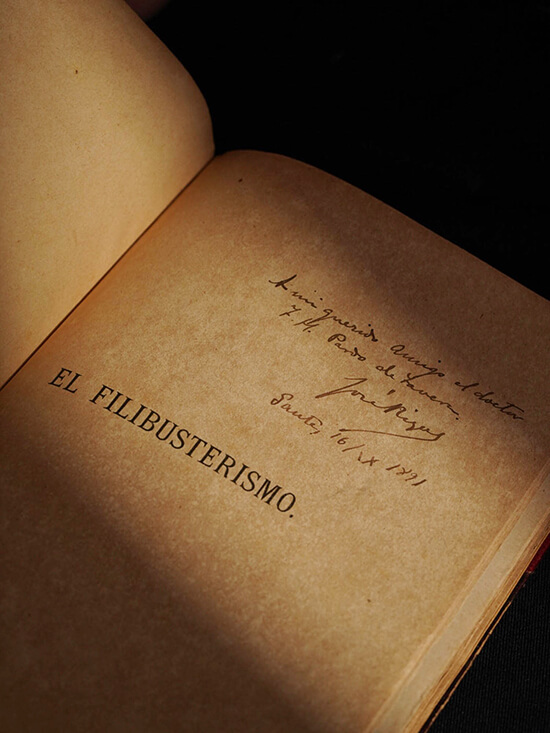

What would have been the casualty of this personal pain and tragedy was his second novel, the highly anticipated El Filibusterismo. But Rizal soldiered on. Too much was now at stake. He pawned the jewels given to him by his mother and faced starvation, surviving on a diet of weak tea and old biscuits. He moved into a cold room in a low-rent boarding house near the press in Ghent to save money by walking. He had even managed to persuade the Boekdrukkerij F. Meyer-Van Loo printers (at No. 60 Vlaanderenstraat in Ghent, Belgium) to agree to a “pay as you go” arrangement; still, the money had run out, and so had Rizal’s ideas that he even seriously considered giving up all hope and burning the manuscript.

The Fili was therefore produced against all odds, defying Rizal’s mental and financial hardships. Leonor Rivera would live on as the tragic Maria Clara who would fade away, imprisoned in a convent by sadness.

One of the first-ever copies off the press—a testament not only of his moral rigor but his desire to see the light of liberty shine in his country— has now appeared for the Leon Gallery Asian Cultural Council Auction, this Saturday, Feb 14. (In the kind of symmetry that the universe delights in finding: an auction that benefits Filipino artists and writers abroad has as one of its highlights, written by a Filipino who created it abroad for the liberation of his homeland.)

Signed and dedicated to his fellow ilustrado and brother in arms, Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera, it’s an important touchstone of our shared history —bringing together Rizal, the Enlightenment, the Philippine Revolution (which it helped inspire), and the First Philippine Republic, the first of its kind in all of Asia.

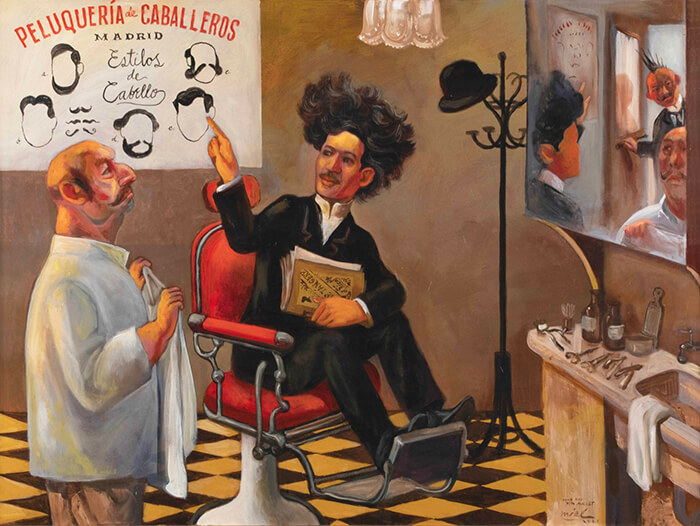

The Leon Gallery auction also threads the old and the new, the 19th-century and the contemporary: one wonderful painting by the sassy, mischievous Dengcoy Miel exudes that main character energy, with Rizal in a Madrid barber shop, wondering which haircut would suit his temperament. He is half-in and half-out of his seat but manages to clutch the original manuscript of the Noli Me Tangere. (Miel, like Rizal, is a Filipino working abroad as a top editorial cartoonist and brings his zany humor to The Straits Times of Singapore.)

Two other paintings also say something about ilustrado ex-pat pursuits; the first, by Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo, captures a woman in red crossing a stone bridge in the Bois de Boulogne, that Parisian park where the Duke and Duchess of Windsor would retire and where the Fondation Louis Vuitton museum rules today. The Bois has long been an escape and pleasure spot for French royalty and a beautiful retreat for the Manila expat crowd, who would often picnic among the trees. It’s an ethereal work, one of Hidalgo’s rare land-based paintings, of the Bois in the pale light of a winter sunrise, amid trees that have just lost their leaves.

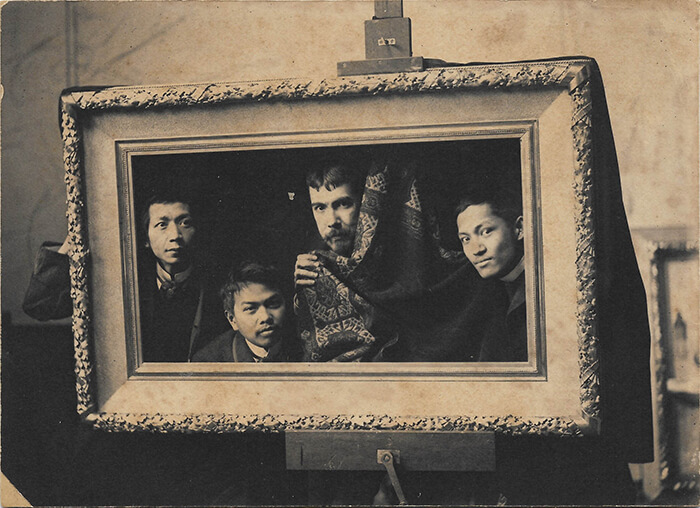

A second painting is by Juan Luna's protege, Gaston O’Farrell, who, by virtue of being descended from the wealthy Tuason family, lived in Paris and moved in the same exalted circles as the Pardo de Taveras and the Roxases. He would meet Luna when he was all of 13 and, since then, had the privilege of being mentored by him.

O’Farrell, in a later incarnation, would become the first Filipino franchise holder of Michelin Tires, the same company today celebrated for the restaurant guide it devised to encourage motorists to travel the European countryside, setting up a tiered system for where to eat on the road.

It was a stroke of genius to tie expensive rubber to luxe fine dining, but the ilustrados certainly knew a thing or two about the power of propaganda, whether in print or painting.

The O’Farrell work is a copy of a Juan Luna—the original now lost in the sands of time and war—depicting the very moment the Katipunan is betrayed by blabbermouth Teodoro Patiño to the Tondo parish priest, Mariano Gil. (No doubt Luna was painting from memory—he had been clapped into prison, and his accuser was probably none other than the noxious Padre Gil. (A second work based on Luna’s “Ecce Homo” from the same period is also in the sale. ) It’s a vivid reminder of the consequences that Luna and Jose Rizal would face for their actions, real or suspected, in the extreme.

If Luna’s “Sumbungan” may be classed as a first foray into a kind of social realism, then two outstanding works take it to full flower.

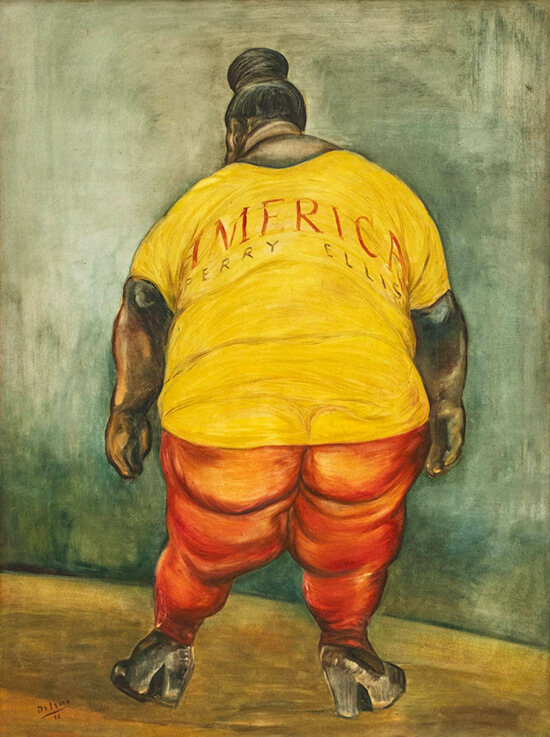

Danilo Dalena’s “America” (created a hundred years after Luna’s) is a satirical take on that country, ironically touted these days as the land of the free, not to mention of milk and honey. Best known for cataloging “the underbelly” of Metro Manila, Dalena brings his quicksilver (but always affectionate) wit to the betting halls of the now-lost Jai-Alai arena on Taft Avenue, the beer gardens of Cubao, the chaos of Quiapo, and even the city’s forlorn public toilets.

It is his first—and last—look at the United States and its people, the working drawings for an intended series having disappeared. A pity, since every inch of this superpower would have made delightful material for Dalena’s mischievous insights.

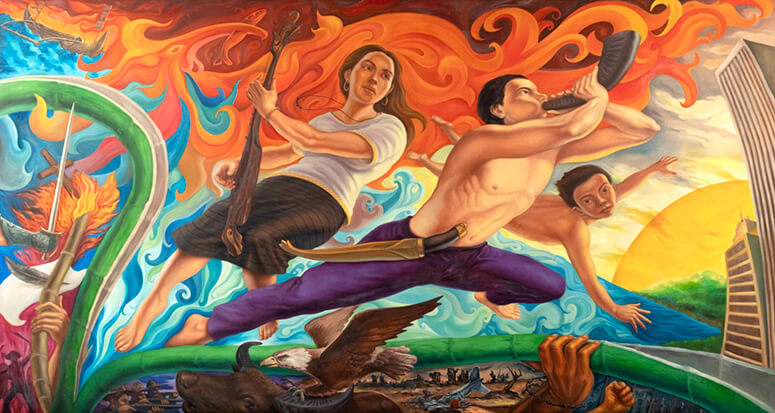

A mural-sized work by five different masters—Elmer Borlongan and Mark Justiniani, Karen Ocampo-Flores, Joy Mallari, and Federico Sievert —is a scene worthy of Botong Francisco. It features young Filipinos rising (kudyapi and tambuli in hand) above centuries of forgotten history. Titled “Paglaom, Padayom,” it depicts moving forward through the power of hope.

Rizal would come full circle with love—in painting the face of a lovely mestiza girl when he was just in his teens, he foretold another perfect love, a face reminiscent of the future Mrs. Rizal, Josephine Bracken. (From the collection of Rizal’s favorite sister Narcisa, it is also a highlight of the Leon Gallery sale.)

Expect to find even more star-crossed, moving works that cross generations at the heart of the forthcoming Feb. 14 auction.