The Fab Four and the Philippine Blues

Having heard more versions of the Beatles’ Manila SNAFU over the years than viewpoints in Rashomon, my sympathies keep shifting: was it the Fab Four’s fault they didn’t get the invitation to visit First Lady Imelda Marcos at Malacañang in July 1966, or was it band manager Brian Epstein’s high-handed dismissal of said invite? Was it overkill when the press went from largely fawning fascination with the Liverpool lads when they arrived here, to pillorying them in follow-up pieces? Was it an overzealous Imelda supporter from the north who orchestrated the NAIA Domestic Airport encounter that most likely led the Beatles to stop touring forever just months later?

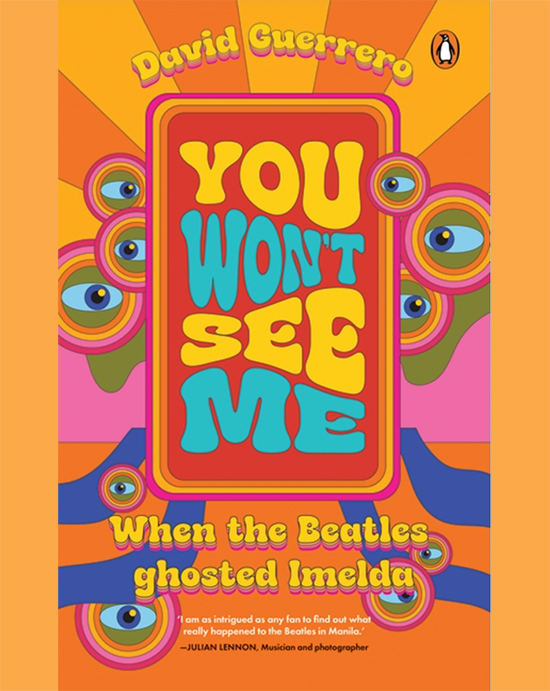

All of this is tackled, once again, in the Penguin book You Won’t See Me: When the Beatles Ghosted Imelda by David Guerrero, a Manila-based writer with an advertising background who coined the DOT tagline “It’s more fun in the Philippines” and also made a BBC World Service documentary called When the Beatles Didn’t Meet Imelda.

The Beatles remain hot property. Several projects are in the pipeline, including an indie film about the Beatles-in-Manila incident, as well as Peter Jackson’s remastered version of the Beatles Anthology documentary for Disney+, which is where I first encountered the Beatles’ personal takes on the whole thing. (Spoiler: They didn’t blame the Filipinos, but did have a very unpleasant experience and vowed to never return.)

Public perception over time has turned the Philippines into the “last straw” that ended the Beatles’ touring days, which is about as accurate as saying Yoko Ono “broke up” the band. Rashomon again: you have to look at all the angles.

Guerrero marshals a lot of on-the-ground evidence, from media interviews and newspaper clippings, to an intriguing group of young Filipino sisters who “stanned” the band when they were staying in Manila Hotel, and even sped in a taxi to follow them to the airport, after sensing that the Fab Four were about to face peril.

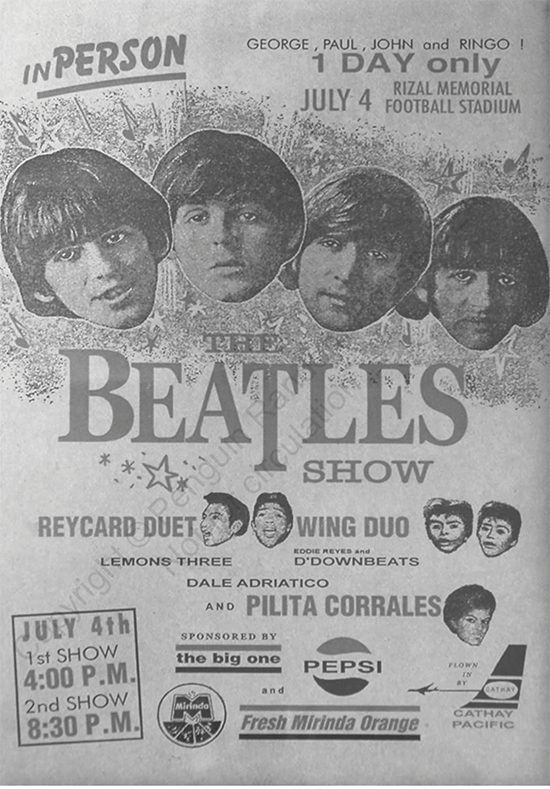

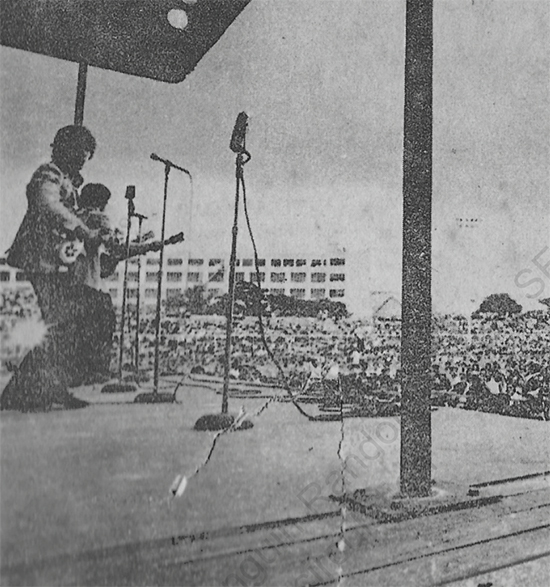

They did. The Beatles, who had concluded two hugely attended concerts on the afternoon and evening of July 4, 1966 at Rizal Stadium, suddenly found themselves personae non gratae after news reports blamed them for ignoring a Palace invite from Imelda; TV stations showed clips of empty chairs where the Beatles were supposed to be, along with a discontented First Lady and sad faces of children “disappointed” by the no-show. That image, reports Guerrero, is how the Beatles themselves learned of the coming storm, watching their TV sets in their hotel rooms.

It all could have been so different. Yet the band had earlier indicated their refusal to attend parties and state visits while on tour after some violent incidents—in one, a woman at a Texas socialite party came at Ringo with scissors, intent on getting locks of his hair. It’s understandable they didn’t want to mix state function with their stated function, which was to fly into countries, sing “Yeah, yeah, yeah” for 30 minutes, crash at a hotel, then fly out again for the next tour stop.

We must remember that the world was changing. Musicians and young people in general were offering opinions on political and philosophical matters, and the Beatles were no different. So there was the inevitable backlash that began as the press and critics began to ask: When will the Beatles bubble burst?

In modern parlance: they now had haters.

In Manila, the backlash came as the press took issue with their smart-alecky responses at a presscon, such as when a reporter asked what they would be recording next. John’s snarky answer: “The Philippine Blues.” How prescient.

The Beatles, as we’ve learned, were hied off from that presscon to a waiting yacht, an arrangement they knew nothing about (tour itineraries weren’t their thing) and set adrift off Manila Bay for the evening before the concert. At a certain point, they balked at the mosquitoes and seasickness and Epstein had them taken to the Manila Hotel instead.

There is something in this story that speaks of the over-exhaustion any visitor to a foreign country might feel when bombarded with kindness or attention. The band seemed to manage their situation from within a bubble, possibly constructed by Epstein, that allowed them to think that matters would always be kept at a distance, or fixed, if they just chilled out a while.

Guerrero delves into whose fault all of this was, and the blame seems to shift between tour manager Vic Lewis, Epstein and local promoters. There are several B-movie side characters who get special mention, like Manila International Airport manager Willy Jurado, who supposedly ordered the escalators and air-conditioning turned off just as the Beatles entered the terminal, toting their own bags. (Jurado was personally offended by the British band’s snubbing of his province-mate, Imelda.)

Guerrero notes that social media and YouTube have allowed certain nasty narratives to persist, even as other Rashomon perspectives get buried in the mix. There’s the damning quote from Ringo in the Beatles Anthology documentary, when speaking of the tour decades later: “I hated the Philippines.” But this should be measured next to his more reflective comments on the visit to a Filipino journalist: “We have nothing against Filipinos, it’s just a couple people in the government.” Yet, which version gets played more on YouTube?

It seems like 20/20 hindsight to suggest anyone at the time really knew how this SNAFU would play out. As I wrote before, it was a case of “Beatlemania rubbing against Marcosmania.” Emphasis on “mania.” And the band was caught in the middle.

Guerrero argues that people here never firmly turn down invites, so their non-response was “tantamount to tacit agreement”—because, you know, Philippine culture. To which I’d answer, sure, people do have a hard time saying “no” here. But they rarely get roughed up at the Manila airport because of it.

One thing is clear, though: “The events in Manila had crystallized their fears and discomfort of the touring life, and now, the band was of one opinion: they weren’t going to tour anymore.” Sayang. But no loss of devotion from actual Beatle fans, like the teen Ponce sisters, Betty, Chato and Vicky, who staked out the Fab Four at Manila Hotel, and got to hang out with the band for their efforts. Now, almost 60 years later, they offer their wishes for peace (“We’re still as loyal as we were when you first came to the Philippines” and “we hope you consider coming back to Manila”), and the invites to the surviving Beatles are still out there, waiting for a reply.

* * *

To order the book, visit: https://www.penguin.sg/book/you-wont-see-me/