Celebrating 1521! Mga sariling bayani: Lapulapu at Ikeng

’Twas on my way to the Mar del Plata Filmfest. We did a detour to the southern tip of Argentina. My wife Katrin and I were tracing that narrow Magellan Strait — a tight bottleneck that could make or break the first circumnavigation in 1521. The spice-seeking Spanish fleet, meandering through a treacherous labyrinth of narrow cliffs capped by glaciers…

‘Twas the translucent-blue tongues of the glaciers licking the salty sea… yes, at The End of the World. That’s what they call Tierra del Fuego, near Antarctica. It might as well be the edge of the flat earth — that was feared ferociously by the crew of Magellan’s expedition. Three wooden tall ships groping 38 days to find a passage to the bigger ocean — what would be named “El Pacifico.”

‘Twas a pinhole opening to the vast Pacific. So why did Magellan call it Land of Fire? Despite the name Tierra del Fuego, the memories of my pilgrimage through the strait are tinted with the cool blue of a cruise, not a hot, fiery orange of a spaceship launch.

Without the guidance of satellite signals, it was the indigenous GPS of Enrique, or Ikeng, Magellan’s slave, that determined the route. His Austronesian seafarers’ cosmology “knew” the way home. Like the homing instinct of E.T., he pointed out the way: which rocky curve to follow or which glacier tongue to avoid. Until they saw the sun setting on a tranquil sea. Enrique could now smell home.

Wow! Another 99 days they sailed the landless stretch of endless blue, before they reached the 7,000 islands of our archipelago. 1521 was long before maps showed the name “Filipinas.” Named after Felipe II, king of the insatiable empire coveting spices. (BTW, he died of syphilis. Parang it almost rhymes with Philippines, diba? Our karma from a colonial name, that’s another story.)

Flash forward to 2021

2021 is the Quincentennial when Magellan’s 1521 crossing of the Pacific is commemorated. Wow, 500 years ago, they sailed three months ever westward — following the sun. The wary crew whispered: “Amigo, when do we fall over the Niagara Falls of the Pacific?” They had run out of food and water — eating the last rats and cockroaches, drinking their own urine — yearning for the end of that endless voyage.

In 2021, I’m honoring, not Magellan, but the circumnavigation by Enrique, his obscure slave /valet/ interpreter. In my eyes, Ikeng was also the fleet’s cosmic guide — who showed the ships the way to the island of his mother tongue.

In 2021, I’m honoring, not Magellan, but the circumnavigation by Enrique, his obscure slave/valet/interpreter. In my eyes, Ikeng was also the fleet’s cosmic guide — who showed the ships the way to the island of his mother tongue. Most western historians choose to write off Ikeng as an uneducated primitivo. Que barbaridad! Eurocentric chauvinism talaga.

It was an Austrian writer who acknowledged the feat of our humble tropical sailor. In a 1937 biographical novel about Magellan, Stefan Zwieg points out the surprise when they arrived in our archipelago: “Enrique was chattering and laughing with the Cebu natives — in a language he had not heard for years, his mother tongue. For the first time in the history of this planet, a human — no matter how lowly his status — had circled the globe and returned to his native island…” Bravo, Enrique!

Today, Enrique’s feat has been framed by kapwa Pinoy artists: Reni Roxas wrote a lovely children’s book, First Around the Globe; Carla Pacis published a work for young readers titled Enrique El Negro; and an original play, Henry the Black, premieres this week in New York by playwright Luis Francia. Works on Ikeng from our POV!

National Artist F. Sionil Jose has paid tribute to Enrique in his novel Viajero — which surely embodies the wanderlust and survivor strengths of our own globetrotter.

And surely my late friend Yoyoy Villame must be belching out his immortal song 1521 with some new lyrics. Siguro bagong eyewitness account ni Enrique sa “Kadaugan ni Lapulapu sa Maktan island… tinepok si Ferdie Magellan, nung April 27 piptin handred twaynti-wan…”

Mabuhay, si Prof. Yoyoy! I’ve included a tribute to my peyborit history titser on the soundtrack of my Ikeng film BalikBayan#1.

All hands on board!! Hoist sail! Ready… camera… action!

Open-ended script; never-ending timetable

Most cineastes have a roadmap (aka the tight script) with a deadline. Others might start to shoot film with no dialogue lists, just distilled concepts, to be translated into celluloid images (a.k.a. the film treatment.)

In 1988 I had no winds in my sails. I decided to shelve the circumnavigation project. My sons were growing up. I didn’t want to sacrifice that bonus of tatay-hood on the altar of a film career. Yes, my priorities became clear: Kidlat Tahimik is a tatay-father and a filmmaker— in that order!

In 1979, it was with a scanty ocean-map that I started my film voyage. It was still the era of 16mm film or “celluloid spaghetti.” Hoy, mga millennials! Baka you don’t know what film is: Once-upon-a-time FYI, long strands of film were wound around a spool. If accidentally unspooled, they became a pile of shiny black noodles. We filmmakers had a pasta menu to choose from. We could shoot Rochester spaghetti (Kodak) or Munich nudeln (Agfa) or Tokyo ramen (Fujifilm.)

In 1988 I had no winds in my sails. I decided to shelve the circumnavigation project. My sons were growing up. I wanted to enjoy being barkada with our three boys. I didn’t want to sacrifice that bonus of tatay-hood on the altar of a film career. Yes, my priorities became clear: “Kidlat Tahimik is a tatay-father and a filmmaker— in that order!” So I put my Bolex 16mm camera in a box and stopped churning spaghetti.

Gusts of old-culture ghosts

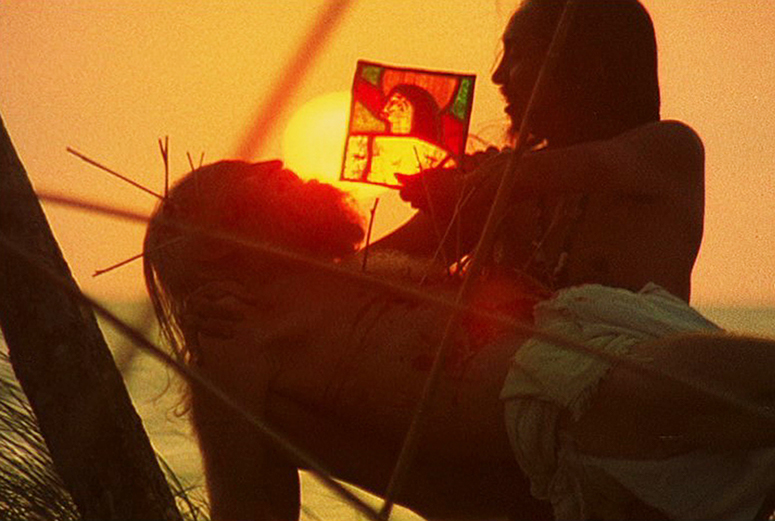

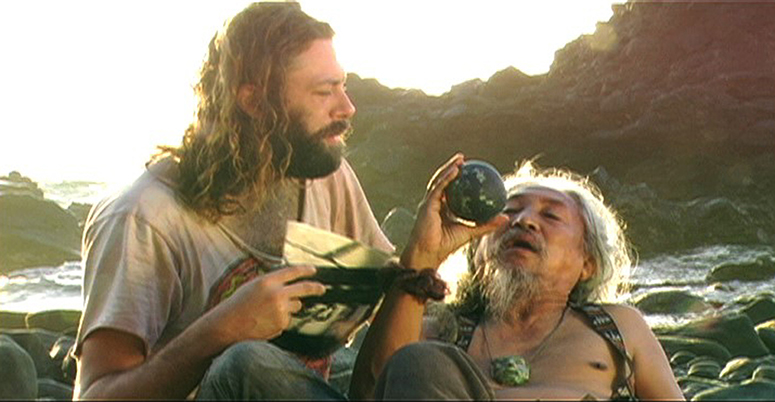

As an indie with no budget, I myself played the indio Enrique in my film. Kidlat Tahimik was the cheapest actor available. And yes, I was always on call for four decades. When I began my film, I depicted the survival instincts of Magellan’s slave coming from his Ifugao ancestors.

Originally the bahag was just a convenient wardrobe strategy. Donning my crimson G-string costume would visually juxtapose the underdeveloped slave Ikeng vs. the overdressed master Magellan. Adopting the indigenous loincloth made easier the job of the costume designer Katrin, my wife. She could focus on designing and sewing the more intricate clothes of European courtesans, from the indigenous weaves of Narda’s textiles in Baguio.

Our new-age movements in the late ‘70s included ethnic-look revivals, returning to our indigenous rituals, and digging out the wisdom of our Cordillera ancestors. This would bring my lenses to capture the waving red G-strings of the Ifugaos — our tribal survivors of those cultural storms Magellan introduced to our islands 500 years ago.

What kind of confused monsters did those kultur wars create within us? Our Pinoy identity is so halo-halo, as described by Chitang Nakpil Guerrero: “We Filipinos lived three centuries in a convent, plus 50 years in Hollywood.” Such displacements of our pre-colonial worldview deepened my curiosity.

Colonization by M.B.A.

It pushed my Bamboo Camera to research how my “over-education” resulted in M.B.A. contradictions — that is, McKinley’s Benevolent Assimilation policy in the early 1900s — when US president William McKinley shipped out 300 American teachers on the USS Thomas to Manila. Their M.B.A. public schools (the DNA of our DepEd today) rebooted our island culture. Dr. Renato Constantino simply calls it the “mis-education of the Filipino.”

Two decades of cultural immersion with my Ifugao mentor Lopes Nauyac in the village of Hapao would awaken me. It became clear how we were robbed of Enrique’s tribal assets by our public school system. This was enhanced by the seductive Trojan Horse of Hollywood. Movies became our informal educators, seducing our culture by the perfumed nightmare of benevolent assassination (sic).

Still windless in my sails, I was a castaway floating here and there. In Baguio it was great to be a hands-on papa with modern parenting experiments. In Ifugao, living the slow-mo life in the rice terraces catalyzed the deconstruction of my westernized mind.

The ancient harmony with nature of the Hapao villagers mirrored to me that growing up in our over-Americanized echo chamber (perfected during the M.B.A. era) has kept us Filipinos out-of-synch with Mother Earth. I had to confront my American Idol ecological demons. And hopefully emerge a greener soul?

Still windless in my sails, I was a castaway floating here and there. In Baguio it was great to be a hands-on papa with modern parenting experiments. In Ifugao, living the slow-mo life in the rice terraces catalyzed the deconstruction of my westernized mind.

While dancing to tribal gongs with my sons in our G-strings, I could occasionally pull out my videocam — to be father and filmmaker at the same time. The prolonged immersion of my sons in Hapao (who in the early ’80s had acted as kids in the film) allowed them to grow old enough in real life, for me to cast them as bearded sailors accompanying Enrique on the high seas.

Ikeng and his indigenous survival kit

For Magellan’s manservant, staying connected with his shamanic ancestors was his survival secret. Ikeng could be a loyal friend adapting to his master’s European-self and, by retaining his islander-self, he could be logistically useful, guiding the expedition home.

As a slave, he could pray with the ship’s chaplain. With the Catholic crew, outwardly he could do the sign of the cross. Closing his eyes, Ikeng would be visualizing innerly, to his ancient mountain gods, and could seek strength from the sea goddesses. On the ship deck he was chatting with the dolphins and whales for directions.

Spiritually balanced, the indigenous slave Enrique was the indio-genius survivor par excellence. It is no surprise he would endure the oppression of slave traders, and not cave in to the protocols of an imposed religion. He remained always connected with his ancestral wisdom.

Stamina-wise, he could tackle the rigors of a 99-day Pacific crossing. Above all, our cool Enrique could float above the violent norm of macho sailors — exacerbated by cabin fever from three years in circumnavigation. (Yes, not unlike the locked-downed people today in our coronavirus prisons.)

By being culturally grounded, he survived two oceans, and the cold curse of European winters on his tropical body, and the racism of foreign lands (long before the age of Brown Lives Matter...)

In the end he circled the globe, bringing home to his island after a long stint in Renaissance Europe his precious “Memories of Overdevelopment.” (Thanks to Luis Francia and apologies to our Cuban filmmaker amigos for juggling their film title.)

A new mantra to sail on

Like Ikeng, decades of drifting to find my film ending taught me to let go my Wharton-MBA diploma-dictated mantra, “Stay on track!” on the road to “success.”

With hindsight, filming a never-ending voyage became a “Straying on track” orientation. Bathala na! (Or as that cute guru Yoda said, “Trust the Force!”)

It allowed me to evolve into a seasoned sailor in the ocean of life. Finally I could take hold of my ship’s steering wheel — more confident in our indio-genius GPS. Perhaps this helped me negotiate daily swells and storms, towards a more tahimik being.

Letting nature spirits guide me to the finish line — scriptless navigation became my “Bathala Na” filmmaking modus operandi. This rendered an inner confidence that I could reach any shore — without a Google map, or an MBA diploma, or a corporate blueprint.

Was that the end result of my inner Magellanic journey?

‘Twas four decades of my filmic voyage to become a relaxed circumnavigator of life. Obsessive, I had been endlessly swimming toward that faraway success island — fighting family/social cross-currents, desperately seeking tailwinds for indie funding, zig-zagging the seas to avoid the whirlpools of colonial pasts.

Finally, the bonus in later life: free-floating to wherever karmic winds push my sails. Straying on track, to arrive at that far-off island — only to find out it has been always within myself. Ayan na. Nakarating rin.

Hoy, Kaibigan! You must first squeeze through your personal Tierra del Fuego. When you survive that baptism of fire, might you transcend that ocean of self-made turbulence — into the realm of the pacific.