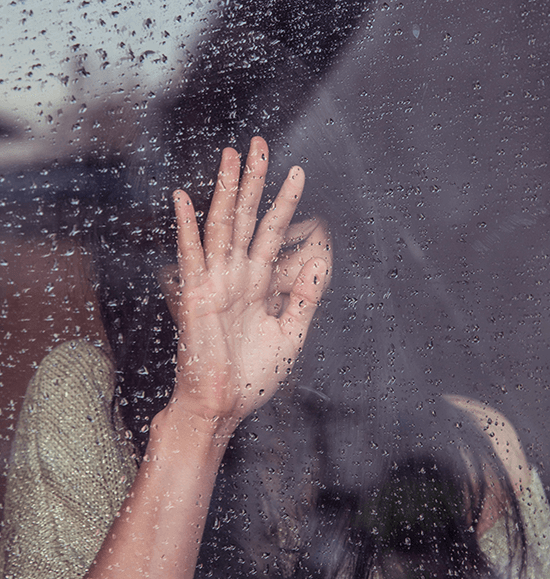

Sick with sadness: Living in the moment of the sad girl

The Sad Girl is the embodiment of all things grunge. In books, she is the beautiful young girl whose heartbreak defines her, a character to be saved by the male protagonist. In films, she is the girl with electric blue hair and a mysterious sadness that others itch to unravel. Online, she posts crying selfies and screams along to “This is me trying,” “Favorite crime,” and all her favorite melancholic music.

She is moody, she is raw, and she is everywhere. It’s clear that we are living in the era of the Sad Girl.

To many, Sad Girl-ism is aimless angst, directed at no particular person or phenomenon. It is merely the desire to be perceived as unique or different. In examining how it glorifies sadness, Rebecca Liu writes, “Soft grunge both beautified and subdued pain, making it consumable and even aspirational.”

Related to this is how the Sad Girl aesthetic glorifies mental illness or illicit substances, which are some of its common features. While discussions on mental health are important, the line is blurred when pop culture’s only idea of mental illness in women is embodied by a waif 20-something whose sadness appears one-dimensional.

After all, the Sad Girl, as Liu further states, “is pretty, white, cisgender, and tortured enough to be interesting but not enough to be repulsive.” In all its angst, Sad Girls in pop culture try desperately to be likable. Where are the plus-size sad girls, the sad girls of color, the sad girls whose burdens require confrontation?

To many, Sad Girl-ism is aimless angst, directed at no particular person or phenomenon. It is merely the desire to be perceived as unique or different.

And because of its popularity, people begin to opt into the aesthetic, spending copious amounts of money to emulate it despite not actually resonating with the Sad Girl. Feelings become embodied by singular objects and paraded on Instagram pages, from taking moody photos of one’s Mitski album to putting Phoebe Bridgers lyrics in one’s bio.

The Sad Girl, in essence, becomes commodified. She becomes a static character whose existence is a ploy to sell more albums or to spice up your Instagram feed.

Pop culture fans argue, however, that artists who get pushed into the Sad Girl aesthetic, such as Billie Eilish and Phoebe Bridgers, are not defined by their sadness. Mitski, another artist swept into the Sad Girl faction of pop, said in an interview, “The ‘sad girl’ thing was reductive and tired five, 10 years ago, and it still is today.”

The sadness of Billie Eilish, for example, is not glamorized or sexy, flipping the Sad Girl trope on its head. The trope is originally reliant on stereotypical narratives of femininity: delicate and socially acceptable because it is beautiful. Think of the damsel in distress, or the girl whose perfect makeup is accentuated by the picturesque mascara trailing down their cheeks. Eilish features a fully-covered body, spiders crawling along her face, and ink-black tears, destroying the beautiful image of the typical Sad Girl. She shows us what sadness looks like through her eyes, demonstrating that creating and seeing different expressions of sadness can be cathartic and make us feel less alone.

Popular media is beginning to break away from the Sad Girl aesthetic, portraying sad women as multi-faceted characters whose sadness is a small but integral part of their larger identity. In Only Murders in the Building, the character Mabel is portrayed as an equal co-host to the two other (male) main characters while she grapples with the loss of her best friend. In Fleabag, the titular character navigates through a similar loss, this time having to wrestle with feelings of guilt due to her perceived accountability in the traumatic event. She is a Sad Girl, but she is also funny, sarcastic, and multi-dimensional.

After all, a huge part of being a Sad Girl is being a girl. Sad Girl Theory, as coined by social media feminist Audrey Wollen, asserts that being a Sad Girl is a reclamation of feminist shame. It forces people to acknowledge that being a woman can be difficult and traumatic. Therefore, Sad Girls find catharsis in being open with their sorrow, screaming at the ceiling, and flinging their angst to the wind. There is a certain value to the openness of it all, destigmatizing the blubbery faces, the rash decisions, the emptiness. There is, also, an inherent value in the act itself — the catharsis of screaming and being.

While it is necessary to break away from the stereotypes of sadness, it is equally important to participate in an open discourse regarding how we navigate the depths of our depression. Maybe there is catharsis in seeing the parts of you that you are ashamed of — your sadness, your angst — reflected back to you in a way that is tangible, accessible, and beautiful.