Why are men so angry?

Masculinity is in crisis, or so our charismatic but slightly problematic titos and emotionally stunted fathers believe. They blame it on the decline of traditional values. According to them, men are disillusioned because we are no longer allowed to be aggressive, destructive, and socially dominating towards other genders—traits that stereotypically characterize patriarchal and conventional masculinity.

In front of the television or while scrolling through social media, they problematize this shift in gender expectations. They complain about women asserting boundaries, queer people taking up space, and other men rejecting the rigid standards of masculinity. For them, men taking care of themselves, wearing feminized clothes, and openly expressing their feelings are equivalent to a society that has gone haywire.

Unfortunately, no matter how toxic and harmful these views are, they can still radicalize men and younger boys, because we were socialized to see these perspectives as the natural order of things.

At a very young age, boys were taught to reject anything slightly associated with femininity, like our softness and vulnerability. Of course we can feel weak, sad, glad, and even scared, but we were taught to mask these feelings. Boys don’t cry, they told us. The only emotion that is socially acceptable is our anger and aggression. In fact, we were conditioned to view our willingness to be aggressive as a measurement of our manliness.

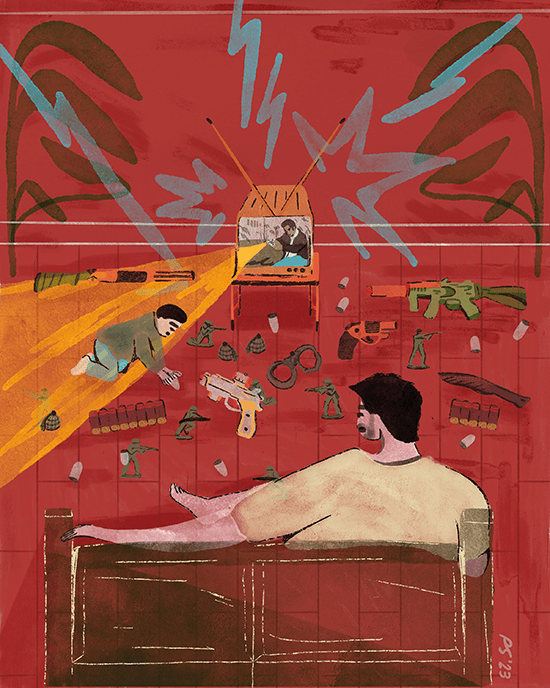

Growing up, the toys that were marketed towards us had violent undertones, such as toy guns, boxing gloves, and action figures. In our playgrounds, we show our intimacy to our friends by play-fighting or shooting them with drenched and hardened paper bullets, because “no homo, bro.”

Even the cartoons and animated shows we watched as little boys had characters that reinforced this socialization. Popeye, the chain-smoking sailor man, was one of the first to show us what it looks like to be a “man.” Sure, he encouraged us to eat our greens, but he also sent the message that to be a hero, we must always be ready to engage in physical fights instead of constructive discussions.

Idealizing this type of masculinity is also a recurrent theme in our media consumption. Walter White from Breaking Bad and the unnamed narrator in Fight Club found their saving grace from emasculation by becoming more in touch with their violence. Cardo Dalisay of FPJ’s Ang Probinsyano and Tanggol of FPJ’s Batang Quiapo exude the same type of masculinity and are celebrated for it. Even our superheroes like Captain Barbell, Spider-Man, and Captain America started as the nerdy everyman, but once they gained muscles and learned how to throw a punch, they became heroes.

Underlying these stories are messages of the inevitability of male violence, as if a man’s only path to self-actualization is through embracing our barbarity.

As a result, even though the overwhelming majority of men are not violent, we no longer flinch whenever we see them act out their rage. When a woman or queer person accuses a man of abusive behavior, there are still many of us whose first instinct is to blame the victims. We act as if men have no agency for their actions because they’re just being, well, men.

We were conditioned to view our willingness to be aggressive as a measurement of our manliness. This doesn’t have to be the case.

Ironically, these rigid ideas of manliness rest on extremely fragile and shaky constructs. For a set of standards characterized by strength, it easily crumbles under the weight of makeup, skincare products, and skirts. It’s so insecure that it’s obligatory and must be proven from time to time. “Real men” must be willing to dominate women and queer people, suppress all emotions except for anger, and put themselves in harm’s way. Failure to do so often results in ostracism.

Having been the kid who failed to play masculinized games, this ostracism dominated my life. Although, yes, I am queer and effeminate, I was still subjected to the same gender expectations as my heterosexual male peers. These are gauges that I failed to measure up to through the years, and it had me excluded and marginalized. But it was also my queerness that opened my eyes to the impossibility of achieving and maintaining this conventional notion of masculinity.

Through failing these tests of manliness, I saw how these gender norms can be so devastating. Men are more likely to disregard their health, abuse drugs and alcohol, partake in risk-taking activities that result in accidents, and take their own lives. In wanting to prove that they are masculine and that they belong, they naturalize, justify, and commit violence, like hazing, which has resulted in enough deaths.

It’s true that men benefit from patriarchy, but they are also literally dying because of it. Recognizing this, however, does not absolve them from the different gender-based hostilities they have perpetrated towards women and queer people; but to refuse to see how it has also victimized them through the years is misguided. It is a system that isolates them, and hinders them from forming and nurturing meaningful relationships. It promises them the world but alienates them from experiencing love.

This doesn’t have to be the case.

Masculinity is not inherently bad, but if we want men to be better, we have to recognize that masculinity can exist outside of patriarchy. Manliness doesn’t have to be a sacrifice of the integral components of our humanity, like our vulnerability, empathy, and compassion. It also doesn’t have to be in conflict with our gentleness, warmth, nurturance, and other stereotypically feminine traits.

We can celebrate masculinity without upholding patriarchy. One of the reasons why I love the art form of drag so much is because it lets us embrace our complexity. It lets us see our beauty outside of our heteronormative upbringings. It is a revolt against rigid gender norms, but it is also a love letter to our identities that don’t sit right with the alpha males of the world. It lets us be us, unadulterated and unapologetic.

The end of patriarchy, then, is not just the liberation of women and queer people. It is also the liberation of men from a system that forces them to see violence as an integral component of their masculine identity. The end of patriarchy is the beginning of a world where our fathers, brothers, and all the men we love, are allowed to show weakness but still be loved for it.