On the other side of suicide prevention hotlines

Trigger warning: suicide, self-harm, and overdose.

It’s past midnight and Aisha, a few hours into her shift as a suicide prevention hotline responder, has just received her fourth call of the day. Immediately, she classified the service user as high risk—he was on the brink of doing the only thing he thought could end his pain: pill overdose, which could shut down his body in no time. She was all set and determined to help him get out of it, but just as she was digging into more details about his plan, the line got cut and another call came in right after.

“I was shaking, but I had to be strong and keep my voice calm for my other caller. She also needed someone to talk to,” she told PhilSTAR L!fe. Thankfully, it turned out to be one of her lucky days. “Once I had finished the other call, the previous caller called us back. He was still in so much pain and agony, but I sensed he had a spark of hope left. He knew there was help.”

“We were able to help him that day,” she recalled, heaving a sigh of relief. Mission accomplished. “But when the next caller came in, I had an intense feeling of tightness in my chest. It was still too heavy for me. I ended up passing the phone to my co-worker as I burst into tears.”

The new callers these few months are COVID patients that don’t feel normal.

Aisha is just one of the suicide hotline prevention responders who consider one call as one of their many battles for the day. As the pandemic continues to keep people cooped up in their homes, they get busier and busier.

In each unpredictable shift, they deal with different kinds of callers: some just want to talk, while others are minutes away from doing it. Their capacity to help is limited to the phone itself—this is because it’s not their job to diagnose nor treat anyone. Their main purpose is to stabilize a patient until they can refer them to another professional or hospital.

That being said, they are left with so many questions that are not always answered by the end of each call: “Did I do enough?” What’s going to happen to them after this chat?” “Will they really go to the hospital I referred them to?”

Being a hotline responder may look like routine work. It involves sitting at their desk and simply answering phone calls, right? But then, it’s not as easy as it seems. It’s a challenging profession that requires strength, resilience, and composure—things that they may lose, but would need to regain right after each emotional conversation.

Suicide prevention hotline calls, by the numbers

Hopeline Philippines has seen a significant increase in their calls since COVID-19 lockdown was imposed in different parts of the country in March last year. “From 800 to 1,400 calls a month, it went up by 300 to 320% during the pandemic and everybody started working overtime,” said Jeannie Goulbourn, the founder of the Natasha Goulbourn Foundation that started the 24/7 suicide prevention and crisis support helpline.

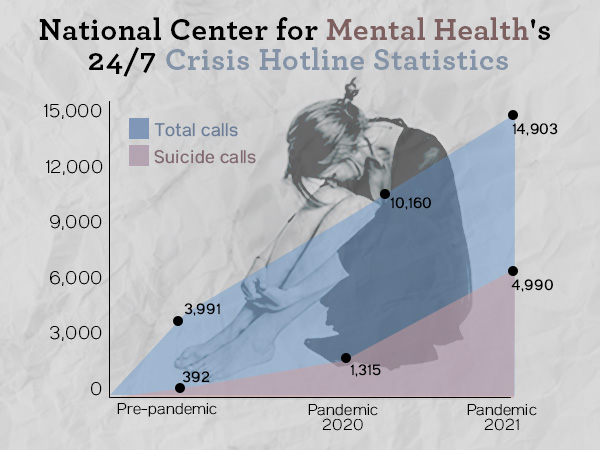

It’s the same for the National Center for Mental Health under the Department of Health: their numbers went up from 3,991 before the pandemic (May 2019-February 2020) to 10,160 during the pandemic in 2020 (March-December 2020) to 14,903 this year (January-September 2021).

Both Hopeline and NCMH’s callers come from different walks of life, with ages between 10 and 92 years old. “The young ones usually talk to us about feeling like a failure, inadequate to continue schooling because their parents cannot afford to get each one a laptop, computer, or a phone,” Goulbourn said, adding that seniors are likewise really high on the scale, who usually talk about loneliness and isolation during this time.

“The new callers these few months are COVID patients that don’t feel normal. ‘I had COVID, natatakot ako.’ There’s also the fear after getting COVID—that they might get it the second time,” she added.

The other common reasons for calling for both hotlines are anxiety and depressive symptoms, family problems, and relationship concerns. “There are some, and it even happened to some of my employees, who found out they’re gay during the lockdown,” revealed Goulbourn.

What comes with the task is intense pressure, but there's also the immeasurable joy of knowing you’re able to save a life just by being there for someone.

For a living, these modern-day heroes offer a shoulder for others to lean on and such a job can take its toll. Note that most of them are licensed psychologists, so they have an idea of what they signed up for. But while they have competitive salaries and certain benefits (like scholarships and courses), some still reach the point of burnout.

How do they deal with these inevitable low moments? “We do debriefing before and after every duty and let them meet with senior psychologists to keep their mental health in check,” said NCMH’s assistant program director Dr. Sharlene Ongoco.

“We also ask them what their usual difficulties are kasi ang hirap din dahil pag-uwi nila, nahihirapan din sila matulog. Iba-iba experiences nila per call eh,” she added.

For her part, Goulbourn said they try their best to take care of them, “so when they get worn out, we allow them to take a rest for three months, take a leave of absence for a year, or just leave and reapply.”

More than just a mental health issue

Hopeline and NCMH have around 12 and 32 responders, respectively—and that’s far from enough. “We have to understand that the crisis hotlines are catering to the whole Philippines: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao,” said Ongoco. They cannot do it alone. While their initiatives have been incredible, they would need a tremendous amount of support from the government so they can serve the Filipino people better.

Goulbourn suggested that a 24-hour service assessment clinic by the government and its local units could be of great help. “Come on! Wake up, mayors. Wake up!” she appealed. “They have to do something because a lot of our callers, maybe half of them, cannot afford a real psychiatric session that is about P2,500 an hour.”

As per the NGF founder, her trusted advisor said that there are not enough licensed clinical psychologists and psychiatrists for over 110 million people in the country. There’s also been a shortage of guidance counselors, according to the Department of Education, which students need now more than ever in the time of distance learning and stay-at-home orders.

The Mental Health Law was just approved in 2018 so it's like we’re still taking baby steps in this matter.

Even the NCMH under the DOH acknowledged that the Philippines is still lacking in terms of the mental health advocacy. “The Mental Health Law was just approved in 2018 so it's like we’re still taking baby steps in this matter,” said Ongoco. “Dumating naman yung pandemic, which is another thing to consider. Our plans really got hampered. We’re still trying to improve our referral systems especially in terms of this.”

While it’s possible, the process could take a while. “Hindi rin kasi siya basta-bastang directive. We have to train the barangays, the police, the LGUs on how to handle suicidal patients,” she said. This is quite understandable as clients have to be comfortable to open up to them first—rushing things could lead to more danger rather than successfully de-escalate crises.

For now, these hotline responders would have to wear multiple hats and do the best they can to fill the gaps. After knowing more about their job, I can’t help but ask Aisha: What makes you stay?

“Honestly, I can’t think of a better job than to help other people get back up. What comes with the task is intense pressure, but there's also the immeasurable joy of knowing you’re able to save a life just by being there for someone.”

She also brought up an added consolation. “Sometimes, the conversation would not end after just one phone call. We have regular callers and there are times they would know it’s me just by hearing my voice,” she continued. “Friendships. Human connection. Nothing compares to that.”

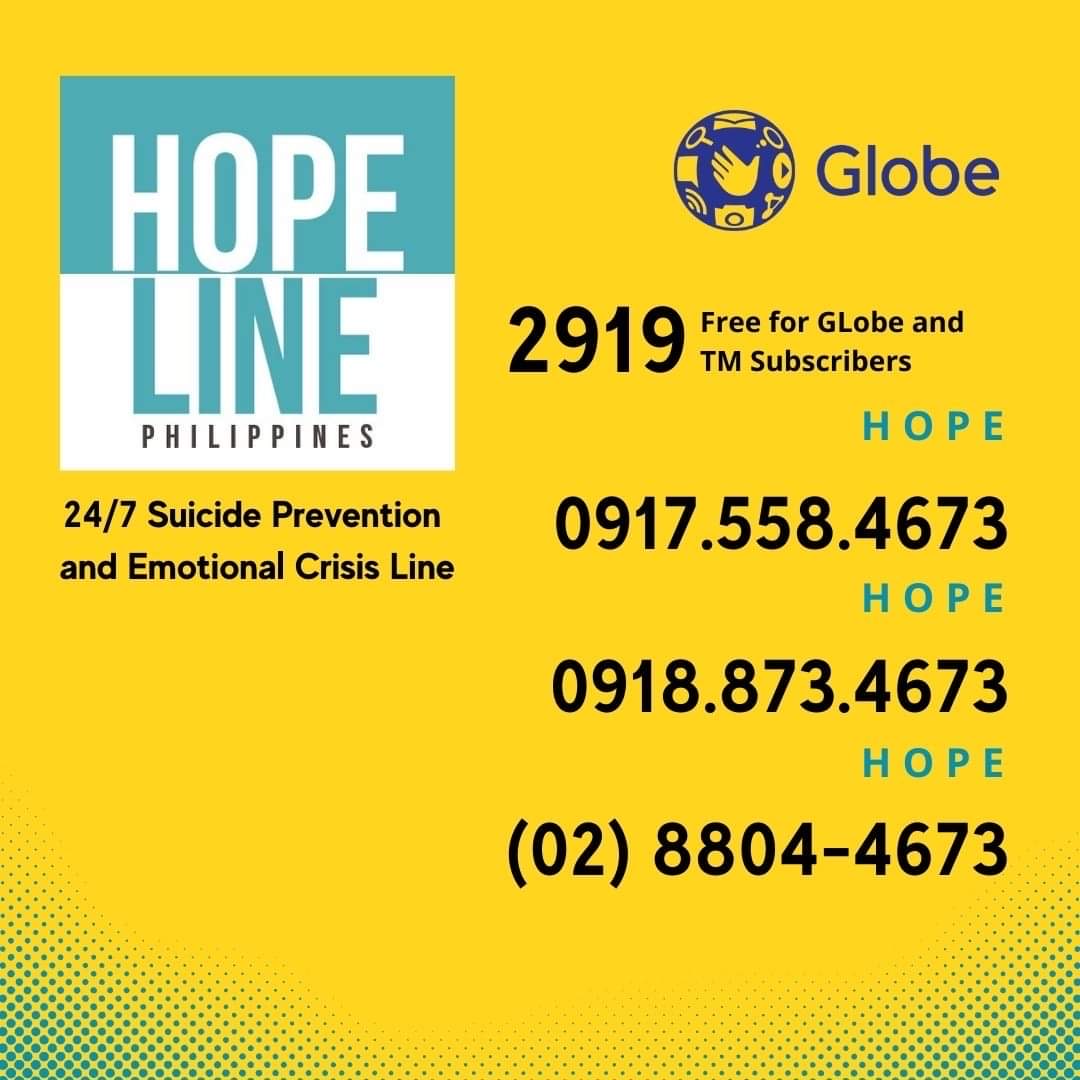

If you think you, your friend, or your family member may be considering self-harm or suicide, you may contact the numbers in the gallery below. You may also reach out to Hopeline Philippines, National Center for Mental Health, and In-Touch Philippines to support mental health initiatives in the country.