Pretty privilege has always been real—but it doesn't have to be

My mom is the most beautiful woman in the world. I sound like I’m buttering her up before asking for a favor, but it’s always been the truth.

With her kind eyes, reassuring smile and fair skin, she is the type of person who quietly commands an attention that lingers with strangers long after they’ve crossed paths. This was evident in the steady stream of love letters she received as a teenager, or the endless praise she’d receive from acquaintances she’d run into in public.

When I was young, I often wondered if I could be on the receiving end of such treatment. I’m my dad’s carbon copy and while he’s good-looking, I thought his traditionally masculine features simply didn’t suit me.

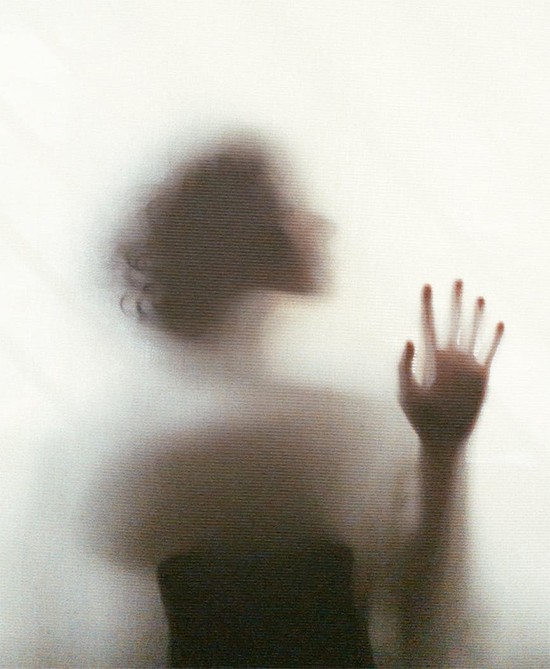

I would shut my eyes tight, mentally reconstructing my face until it looked more like my mom’s. She hated it when I wished to be anything other than myself, claiming with her signature wisdom that I was beautiful the way I was. But was that even possible?

With the dominant cultural landscape shaping our notions of beauty over the years, it seems we’ve unknowingly agreed on a singular definition of what it means to be pretty.

Everywhere I looked, from TV to Total Girl, it was mestiza celebrities with skinny frames and shampoo commercial-ready hair—basically my total opposite. Those who also failed to meet these arbitrary standards struggled to find representation in mainstream media and thus fell outside of what was considered beautiful.

I did everything I could to change that: perhaps just a few hours at the mercy of hair straighteners, a pair of colored contact lenses, and a little less chub at the hip would do the trick. But I would only ever be called “cute” or “charming,” compliments that seemed to be reserved for when there was literally nothing left to say.

And so I watched this so-called pretty privilege benefit those who had it in spades. I often tried to compensate for my lack in this department and earn attention in other ways. I was the star student, then the designated group leader, then later on the one with the most obscure taste in music or most coordinated Instagram feed. But no matter how many labels I made for myself, I wasn’t the type that people gravitated towards, despite little to no effort.

If someone is easy on the eyes, the enjoyment we derive from looking at them colors our perception of their other attributes. This bias makes us more likely to view them as intelligent, healthy, and socially capable, thus more worthy of our attention and support.

“Isn’t it unfair that I literally have to be all these different things for people to notice me, while other girls get praised for existing?” I once told my best friend during a routine chismisan session in the communal restroom. This earned me a resounding “Inggit lang yan, girl.” All succeeding attempts to air my grievances would be pegged as simple sourgraping: apparently, my accusations were grounded in jealousy rather than based on solid evidence.

It turns out pretty privilege has existed long before we knew what to call it. Modern psychology points to the “halo effect” as evidence: if someone is easy on the eyes, the enjoyment we derive from looking at them colors our perception of their other attributes. This bias makes us more likely to view them as intelligent, healthy, and socially capable, thus more worthy of our attention and support.

This treatment has historically (and sometimes unfairly) afforded the conventionally attractive with better job evaluations, longer romantic relationships, and even less severe sentences and jail time.

“There’s a cumulative effect at play, as well,” explains social psychologist Tonya Frevert. Those with pretty privilege “become more confident and have more positive beliefs and thus take more opportunities to demonstrate competence.” Given the advantages that come with being on the right side of the spectrum, it’s no wonder communities often celebrate those who undergo drastic glow-ups or weight losses, to the point where they’re put on a pedestal and perceived as a life peg.

But one thing my past self failed to take into consideration is that it’s not the conventionally attractive girl who is the enemy, but the patriarchal system that constructs these standards in the first place. The “pretty” one probably has it just as hard as the rest of us; she’s simply become easier to blame.

By collectively fixating on their looks alone, we often flatten such women into two-dimensional personalities and reduce their worth to the way they look. As a result, they often live with an unshakable fear that the privileges afforded to them will instantly be revoked if they exhibit even the slightest change.

People don’t like to admit such a phenomenon exists though: many remain in denial of its existence, even if it literally blew up as a TikTok trend earlier this year. After all, who wants to own up to perpetrating a culture that discriminates based on something as shallow as outer appearance? However, denying that it is an ongoing occurrence that hurts and harms everyone involved does no one any favors. Looks do matter… but they don’t have to.

Thankfully, society has made strides towards redefining beauty. We now see fat, dark-skinned, disabled women starring in western shows or strutting on international catwalks, shutting down the notion that perfection is embodied in a single stereotype.

However, this forces us to look inward and examine if we uphold the same value of diversity on this side of the world. Do our media outlets and brands truly advocate for the multiplicity of Filipina beauty, or do they simply give tokenistic support to show they’re keeping up with the times?

Besides this, we can further improve our progress by watching the emphasis we place on beauty. We shouldn’t applaud those with acne scars and hyperpigmentation for going out without makeup, or tell fat women wearing skimpy clothing that we admire their confidence. While well-intentioned, such comments imply that these normal physical attributes are flaws that should be hidden out of shame and gawked at when exposed. In reality, there is nothing brave about choosing to look and feel human in public spaces.

Such conversations may be tough to have but are crucial in pushing for more inclusive and realistic standards. As Gretchen Henderson, author of Ugliness: A Cultural History, says in an article for Girlboss: “We are living history, we are not only inheriting past perceptions but engaging with—or alternatively, ignoring or denying—them to co-create tomorrow’s future.”

We have the power to divorce a woman’s worth from her physical appearance and encourage this same behavior in the succeeding generations of girls. One day, our daughters will look at themselves in the mirror and truly like what they see, and can genuinely say the same about those around them. If that doesn’t look like a future worth working towards, then I don’t know what is.