A heritage of implicit complicity

Under an unbroken string of colonial experiences for nearly four centuries, there were always myriad chances of acceptance, cooperation, coordination, collaboration, or, when an ill wind turned a moral compass, complicity. Most Filipinos may be said to have often swung from one option to another, whether these involved either personal benefit or practical pretense, perhaps anchored on a patriotic decision to do right by one’s countrymen.

And when the colonial yoke was finally lifted, the irony grew strong with the transfer of power to a succession of questionable leaders that commanded loyalty in the name of hapless motivations.

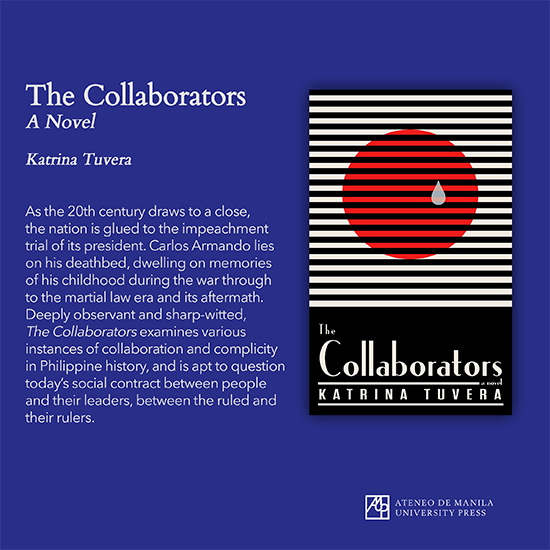

In her 196-page second novel, The Collaborators, Katrina Tuvera admirably explores these complex psychosocial ramifications with her fluid prose that ever rises from the simpler landscapes of familiar backgrounding.

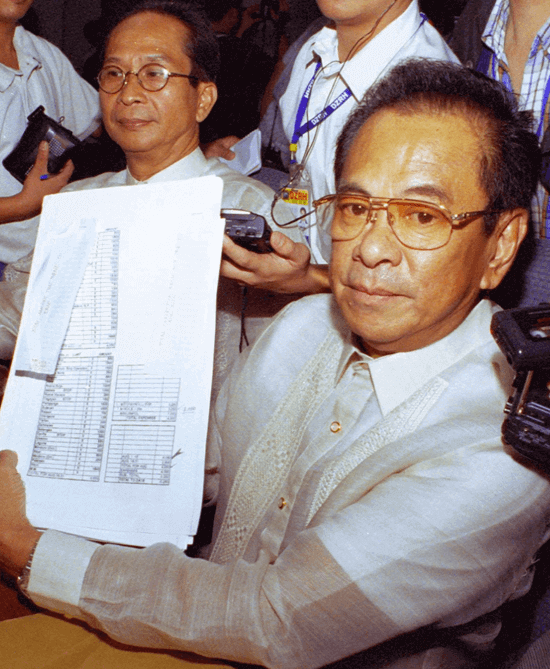

Contemporarily, the political matrix begins with Chavit Singson’s turnabout from then-President Erap Estrada’s inner circle, owing to suspicion that he was about to be rubbed out.

Fictional characters comment on the proceedings that lead to impeachment and EDSA Dos. But this score of characters are also paraded in constant flashbacks that take everyone to their original provenance—countryside settings far from but eventually serving as stepping stones to imperial Manila.

The flashbacks go all the way back to collaboration with the Americans and Japanese. While there was much hope that MacArthur would return, wealthy landowners palavered to mutual benefit with Japanese lieutenants. With liberation and so-called independence came The People’s Court. Thence bandits and Huks had running encounters with the PC, or Philippine Constabulary. Shades of transgression and guilt, or avowals of innocence, danced with allegations of treason—much as in a rigodon.

But when does complicity become treason, when a people kept inheriting the same arguments as to what distinguished the implicit from the explicit? All that might have been produced were volumes on situational ethics.

Throughout, Tuvera establishes the bonds of family and regional comfort zones that often suffered weakening on account of philosophical, ideological, psychological, and fundamental differences. Most were a function of character, of biases, of individual classification between the vanguard and the joiners. And let’s face it, financial considerations.

Generations underwent a skipping continuum of contretemps and challenges.

“Their elders called them martial law babies, children born under the spell that lasted twenty-one years, a tag that damned and dismissed a whole generation as forever infantile, programmed by the New Society. But even children could see from the corners of their eyes: White-washed walls that rose to mask the slums from a visiting Pope John Paul II, blurred pictures of a man in black shot to death on some stage, after he rushed at the First Lady with a machete. 'What do you know?' the elders would say. 'You’re too young, you’re a martial law baby.' But even children could wonder: If we were so ignorant, what to make of them, the adults, who think they know better?”

The expository voice proclaim thus, on such occasions when it’s allowed to take over. Otherwise, the judgments are rendered by a score of characters, some more fleeting than the others, albeit taking significant part in the patched narratives.

Of Erap’s comeuppance, minor characters weigh in on the mediagenic drama, until someone ends the section with his unspoken thoughts:

“A second EDSA. This time, Carlos restrains himself from replying. Whatever for, if the first was such a success.”

No contemporary leader escapes the conversation that relates to conventional wisdom, although here we might wish as an eavesdropping reader that the prescience extended farther into the future. Or that the writing of this intriguing novel hadn’t been executed prematurely.

“‘Politics is so teleserye. Take the VP. She only won because she looks like Nora Aunor. Down to the mole.’

“‘At least she is Nora with an Econ degree.’

“‘And these Ilocanos!’ scoffs the mother. ‘Making Bongbong governor! Watch out—they’ll be sending him to the Senate next.’”

The hometown of San Roque is a constant refrain in the flashbacks. It’s during his boyhood there that the central character Carlos undertakes long-lasting lessons from both his Bible-reading mother and his father, a teacher called Maestro who holds some moral sway among the town mates. It is also where Carlos often harks back in idyllic memory to his pleasant times with boyhood friends enjoying the nearby creek and forest. But these recollections are also rife with eyewitness instances of physical confrontation and violence, all manifesting man’s domination and betrayal of others.

It is in San Roque that the novel concludes with the ultimate flashback, soon after a decision made in his prime—despite his prevailing station of collaboration—reassures Carlos of his own ethical moorings.

The hopscotching narrative may occasionally confuse a reader, especially when a character whose final fate is already known to us reappears within an earlier timeframe.

I also find Renata, Carlos’ lifetime partner, difficult to empathize with, as in her maturity she appears to have gained inexplicable contrariness. Their daughter Brynn, who understandably prefers her father’s company, is similarly headstrong, so that her scenes with her mother always seem fraught with orneriness.

But at worst these quibbles are a minor distraction. Tuvera has expertly mapped out her intricate history of Filipinos’ engagements with dominating forces—both from without and within.

Katrina Tuvera has authored Testament and Other Stories (2002) and The Jupiter Effect (2006), her first novel. Her work has won a Carlos Palanca Memorial Award, the Philippines Graphic Award for Literature, and the National Book Award. The Collaborators was published early this year by the Bughaw imprint of Ateneo de Manila University Press.