Publishing as truthtelling

As I write this, I learn of the massacre of the Fausto family in Himamaylan, Negros Occidental.

On June 14, a farmer couple and their children, aged 15 and 11, were gunned down in their sleep by the 94th IB of the AFP. The mother was a member of a peasant organization fighting for the rights of farmers. Reports say that the family had previously endured at least two incidents of illegal search and seizure; in March, the father was tortured and interrogated by the military and forced to admit to being a member of the NPA.

The AFP later claimed that the Faustos were killed by the NPA in retaliation for being government assets, a claim refuted by the victims’ relatives.

Among the many statements of outrage and condemnation of the massacre is a poem by Luchie Maranan, a cultural worker based in Baguio. The last stanza goes:

Tahimik ang paligid

Ng munting libingang iyon.

Akala nila’y

Tatahimik ang ibang palayang

Sumisibol ang pagtutol.

It was quiet

Around that tiny grave.

They thought it will be silent

In other rice fields where

Dissent grows.

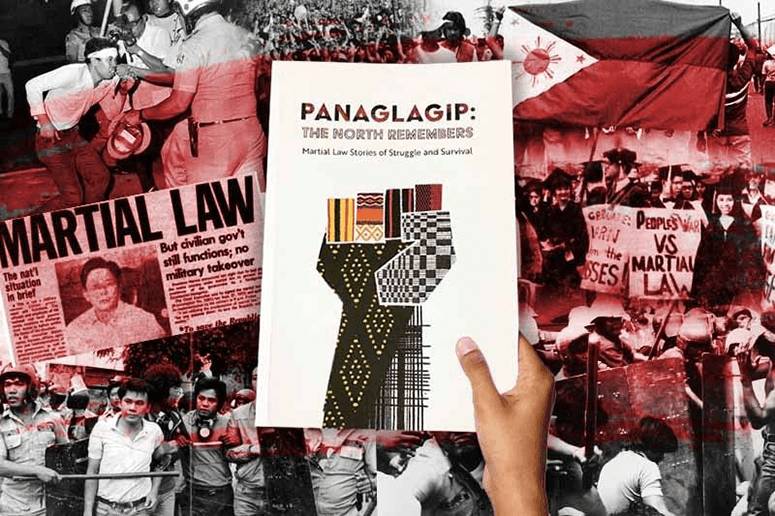

Luchie is co-editor of Gantala Press’ latest book, Panaglagip: The North Remembers (2023), an anthology of personal essays by former political prisoners in Cordillera and Ilocos during Martial Law.

Gantala Press was formed in 2015 as a women’s press. For better or for worse, we thrived in the time of Rodrigo Duterte’s shoot-them-in-the-vagina misogyny, the Marawi Siege, his war against the poor, the all-of-nation approach to counterinsurgency, and the Rice Liberalization Law. In a way, we were forced to reckon with all of this terror through our art, our publishing work. Our luck was in meeting women from the people’s movement who have since kept us grounded in the newfound, important task of advancing genuine liberation, not only of women but of the Filipino people.

Through the years, we have come to realize that ultimately, Filipino women confront the same issues that the majority of Filipinos do. On top of these issues is the question of land: farmers, fisherfolk, and indigenous peoples are red-tagged, harassed, imprisoned, and killed so that land can be grabbed, sequestered, or converted for the interests of multinational corporations.

“Our luck was in meeting women from the people’s movement who have since kept us grounded in the newfound, important task of advancing genuine liberation, not only of women but of the Filipino people.”

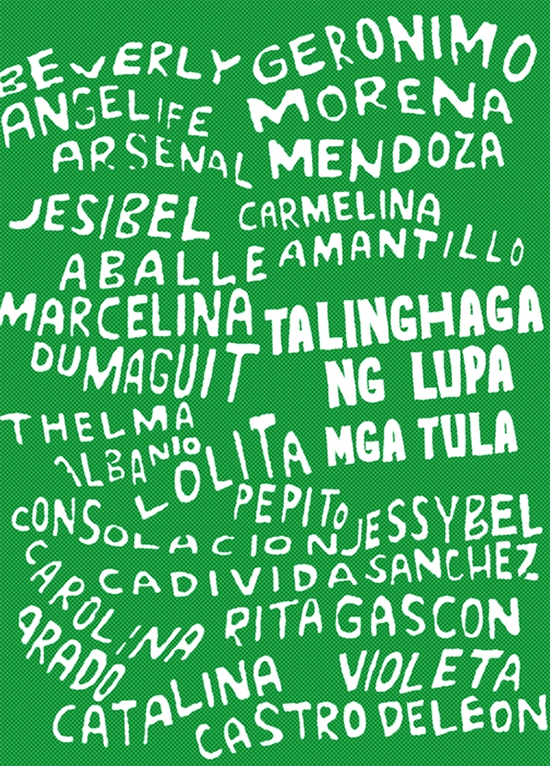

Since we have been publishing works by women, especially women from marginalized sectors, exposing the land problem has naturally become central to our work. In 2019, Gantala Press and the Amihan National Federation of Peasant Women published the poetry chapbook Talinghaga ng Lupa to commemorate International Rural Women’s Day. In “Iloy nga Baganihan,” Christine Joy Capaducio of Amihan-Panay tells of the militarization that ravages the countryside. This includes AFP soldiers stealing chickens and carabaos, entering houses and taking money and jewelry, and forcing farmers to surrender as “rebels.” Government soldiers “should be protecting our homes / but instead, they create chaos / you will be killed if you complain,” go some of the lines written in the vernacular.

State forces not only commit murder but also slander. Peasant leaders asserting their rights are often falsely accused of being insurgents, with the NPA also being wrongfully labeled as “terrorist.” Farmers are shot in their sleep and then maliciously reported by the AFP as killed in an “encounter.”

The Himamaylan Massacre is an extreme form of state attack on the people – a terrorist attack – that has been happening since the Filipinos began fighting for national sovereignty. During US imperialism, the right to till the land became fundamental in the people’s struggle. Imperialism is also the force behind development aggression that intensified during Martial Law. In Northern Luzon, as Joanna Cariño chronicles in Panaglagip, “Marcos crony Herminio Disini was awarded 200,000 hectares of communal forests in Abra as a logging and paper pulp concession. Four mega-dams were to be built along the Chico river as the flagship energy project of the dictator in response to the global oil crisis. … A major issue in Cagayan Valley … was the acquisition of Hacienda San Antonio and Santa Isabel by crony Danding Cojuangco in order to set up his ANCA corporation. This would have displaced the tenants who were expecting to finally own the land after the expiration of the colonial royal grant to Tabacalera.”

“In this war, truth-telling and evidence-based information serve to counter the enemy’s blatant lies.”

These state attacks sparked the growth of a popular anti-imperialist movement along with an agrarian struggle that persists to this day. A civil war has been going on for decades. A revolution is being waged.

In this war, truth-telling and evidence-based information serve to counter the enemy’s blatant lies. And women have taken on this task, faithfully documenting state oppression as well as the people’s resistance. We see this in the books that we painstakingly and painfully endeavor to publish. We see it in Sa Aking Henerasyon, the collected poetry of Kerima Lorena Tariman who was also martyred in Negros as a people’s soldier. We see it in Binhi ng Paglaya, the prose and poetry of peasant women organizer Amanda Socorro Lacaba Echanis, one of the hundreds of political prisoners in the country who refuse to be silenced.

In women’s writings we see the revolution that is happening in the countryside. And as a Filipino women’s press, it is our privilege and commitment to help plant the seeds in the unquiet fields.