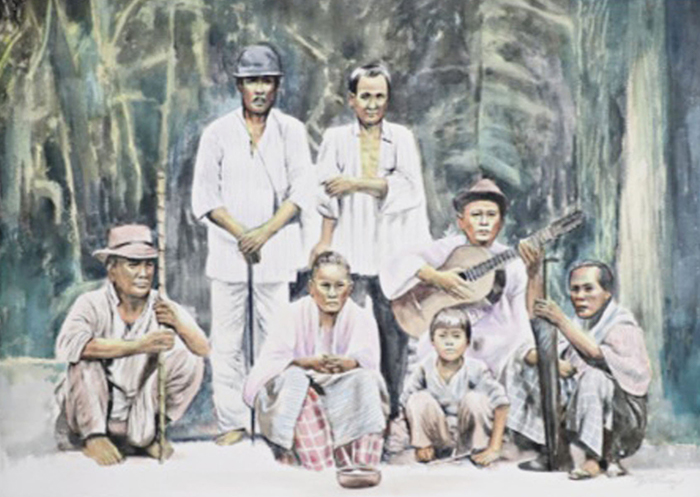

This is what history is—a story set in reality, with characters that lived among us

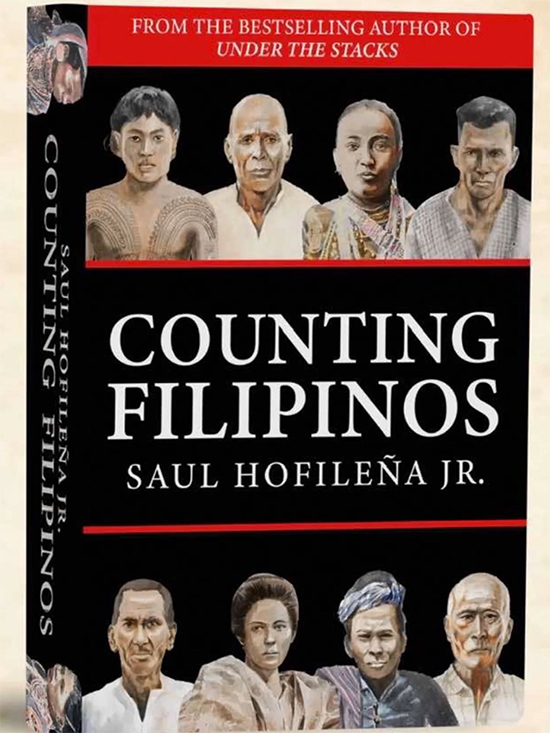

Attorney Saul Hofileña Jr.’s Counting Filipinos is a critical examination of how numbers and statistics hold a deeper meaning in shaping the understanding of Philippine history and identity. Instead of simply presenting numbers, this book dives deeper into the role of classifications and finds the narrative within the given statistics. A recurring theme was the fact that from people to supplies, everything was “counted” and through the author’s thoughtful analyses, it is emphasized that though tracking amounts is an effective record-keeping strategy, it does not accurately capture value.

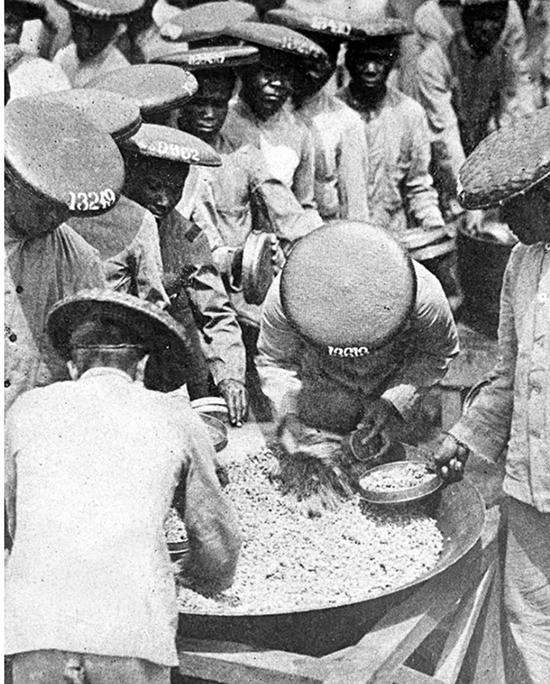

The book begins strong with the first chapter entitled “The Salt Seekers” which revolves around atrocities from the Japanese Occupation that are often overlooked or sanitized by modern curriculum. This chapter was graphic and did not shy away from the truth encouraging a courageous attitude for approaching historical text. With interviews weaved into the examination, it is also an example of handling personal stories with care. History was not always pretty, and to sugarcoat violence obstructs the view of the truth. Personally, this chapter was the heaviest but effectively set up how “counting” was going to be approached. After this start, the book does get lighter.

Through emphasizing the qualitative nature of what was being counted, Hofileña does not reject the usefulness of enumeration but instead encourages a more critical approach to it. A single percentage may never fully capture the lived experiences, struggles and resilience of Filipino communities. The book makes readers reflect on how easily numbers can simplify complex realities. Counting goes past its role as a quantitative method and is presented as a cultural and political act that reflects power struggle and agendas. To illustrate a quantitative method qualitatively was an arduous task that Hofileña succeeded in carrying out.

| Published by Popular Bookstore Xiao Chua/Facebook

Each chapter makes a case on how Filipinos were “counted,” categorized and represented and how this contributed to our history. Do not be misled by the book’s title because not every part of it focuses on actual counts and numbers. There are many chapters and sections which give thorough and genuine deep-dives on specific people, figures, etc. but also sections which support historical contexts and side stories that give readers a clearer picture of the topic. The author does not make use of footnotes and instead provides detailed endnotes in order to prevent his book from reading like a thesis. Without giving away too much, there were a few chapters that stood out to me because of how they approached known topics from a different angle or provided information I had not previously come across.

About halfway through the book, Chapter 15, entitled “The Strange Science of Dr. Sixto de Los Angeles,” weaves the named doctor’s life together with the practices of criminal anthropology and forensic science. This included Dr. Sixto’s theory of blood pressure being connected to murderous instincts. The chapter starts off with a photo of what are allegedly Andres Bonifacio‘s bones discovered by Guillermo Masangkay, accompanied by Dr. Sixto. From here, Hofileña connects this discovery with President Aguinaldo’s execution orders for Bonifacio to help readers place Doctor Sixto in the narrative of Philippine History. He goes further by discussing Dr. Sixto’s respect for anonymity and identity by using prisoner numbers to identify his subjects but also takes note of possible racist tendencies with how he considered and measured physical attributes for his study. It is in this chapter when Hofileña puts his challenge of “questioning the beloved” into practice. Whether this taints one’s legacy is up for readers to decide.

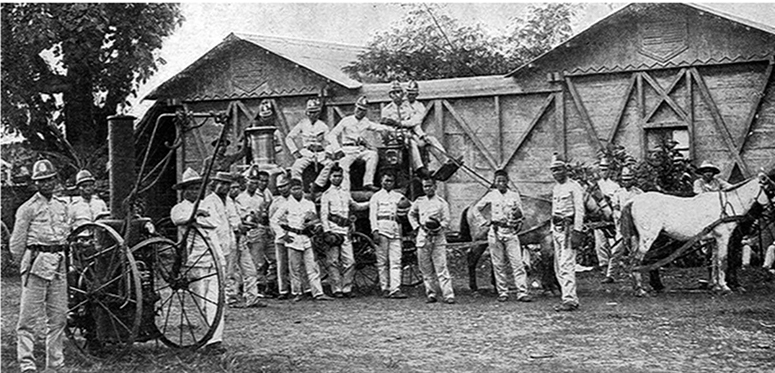

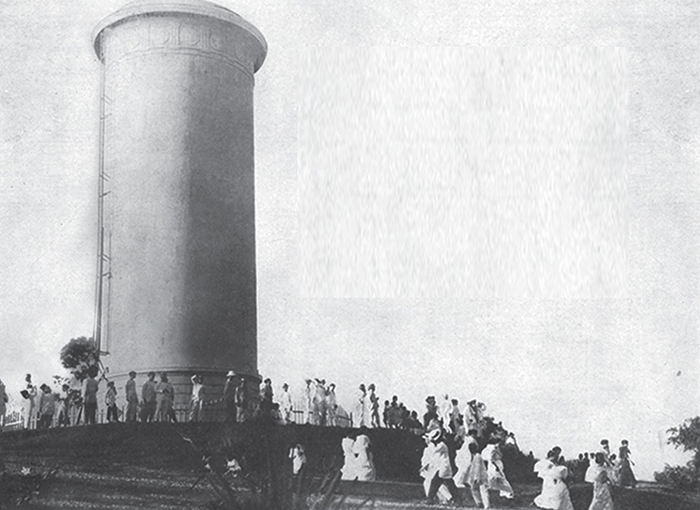

The next chapter, Chapter 16, is entitled “Smoke-Eaters and Firefighters” which highlighted how fire literally restructured places and through this, also reshaped culture. In the Philippines, we can consider fire an element that has landscaped history. This chapter chronicles the cycle of how fires would start and be subdued from the 1500s until modernization and the role of firemen in these tragic events. It also brings up specific fires including the many in Intramuros over the decades and Rajah Sulayman’s Manila. This chapter also highlights a story from a Jesuit missionary named Father Antonio Sedeño who was an architect and helped his area adapt to growing fire. However, it was included that none of the measures and stories mentioned were enough to save Andres Bonifacio’s house which still had his beloved books showing readers a more personal impact of fire.

Finally, a chapter entitled “Cuadricula, a Starting Point” which discusses the grid pattern for colonial towns. Cuadrícula is a grid pattern with a central square and connected streets which proved to be organized and efficient. To visualize, Intramuros is laid out in this style — it is just one example of this system which was also applied in many other countries. Though this layout may appear beneficial because of its straightforward nature, it may not have been designed for the benefit of its residents but instead for the maintenance of power. This chapter detailed the possible weaponization of urban planning and how these systems were used for keeping people in their place and for carrying out personal agendas. Like its title, this chapter is a starting point to discuss roads, bridges, and how Spain brought itself around the world for both commercial gain and spreading the Catholic faith.

A few subsections were also impactful including those regarding the fight for territories and sovereignty, and a sequence about Max Huber and how the Philippines was once entangled with the Dutch. The young adult or YA reading generation may also appreciate the section about “La Quinta” or conscription, which to me draws similarity with the concept of The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins. Though one is a work of fiction, and one a record of fact, the similarities in concept are a firm example that patterns like this recur across cultures and time periods.

I appreciate when history is told in an almost novelistic manner, like a story, instead of simply laid out in a timeline. At the end of the day, that is what history is—a story set in reality, with characters that lived among us. The author lets his passions and beliefs shine without tarnishing facts with personal bias. Hofileña does not dictate what the reader should think; instead, he raises thought-provoking questions that call for reflection. The book’s main strength was in how it deepened the meaning of numbers and gave them roles to play as part of a larger story. Numbers are usually treated as simple facts and records, but Hofileña reminds readers that each of these numbers stood for a decision. What needed to be counted? Who had to be included? Why? Outside of what each chapter outlines, this encourages the reader to question how and why information is gathered and presented. Though I am unsure of the author’s intention, Counting Filipinos is relevant to the present day. With our constant exposure of counts including previous COVID numbers, employment figures, rates and more in newsroom discussions, we forget the stories behind those numbers and the humans they represent.

Additionally, what makes the book engaging is how readers are encouraged to question everyday assumptions. Countable figures, population statistics and demographic data may usually be taken at face value and as simple facts. However, Hofileña reminds us that behind these numbers and data is a decision about what to count, who gets included, and how people can be classified. As a reader, this realization can make one more aware of how history is shaped not only by events but also by the ways information is gathered and presented.

Hofileña’s writing is analytical and clear, making complex ideas understandable without oversimplification. Although the subject matter involves statistics and history, he avoids overly technical language, making this suitable for students, professionals, and anyone with interest in Philippine history, sociology or political studies. He makes use of concrete examples to guide readers through layered ideas without spoon feeding them. Readers aren’t pushed to think what the author wants them to, but rather push themselves to form their own opinions, with an exception for the last chapter. For students of Philippine history, the book offers a refreshing complement to traditional texts by focusing on structures and systems rather than events alone.

Attorney Saul Hofileña Jr. invites his readers to open their minds and question the beloved and what one may be used to; to dig deeper into each story’s protagonist and see that these heroes can be both scrutinized and misread. Counting Filipinos is a thought-provoking read that will certainly deepen one’s appreciation of history. A good addition to any Philippine History collection. By revealing facts and figures that are often overlooked or sanitized in classrooms, readers are pushed to think critically and reflect how beyond amounts, numbers carry both value and stories, shaping national identity and social understanding. This book is a reminder that history does not only stand in monuments or live within prose but are also found in tables, forms, and census reports. Counting may never have been an innocent act of record-keeping but a system that influenced power structures that have trickled down to the present day. By giving further context to what has been counted, Hofileña Jr. invites readers to see Filipinos not just as numbers, but as people whose lives cannot be fully captured by statistics alone.

* * *

Counting Filipinos by Saul Hofileña Jr. is now available for purchase in Fully Booked.