Subtle art of fear: The evolution of feminism and horror

Women have always been monsters. Since the beginning of time, stories and illustrations of fear were simplified into the feminine form.

The Greeks portrayed the terrifying snake-woman, Medusa, to be the destroyer of man. Pandora, the first woman created by Haphaestus, god of the forge, shows that only chaos is brought from giving freedom to women. Interestingly enough, stories from the other side of the globe show that this trend is not exclusive to the West. Whispers of man in their tellings of Eastern horror stories almost always take the shape of a woman as well, many of which include Thailand’s disembodied demon woman Krasue, China’s Fox Spirit Huli Jing, or the famously known aswang from the Philippines.

During the beginning of mainstream horror in the 18th-century Gothic era, it was in between the lines of the era’s scary novels that embodied the true intentions of the literati and novelists—coincidentally men in male-dominated fields.

Whether it be a ghoul feeding on naughty children or a villainous temptress, the ill-tellings of female characters always inherited ideas of anger and disgust, perpetuating the outlook that the horror genre became a literary weapon against womanhood. Seen in Matthew Lewis’ The Monk or Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, the monstrous female trope became nothing more than a mocking symbol to the first wave of feminism, warning readers that powerful women would only generate chaos.

This oppression seemed to grow worse upon the evolution from literature to motion picture, promoting gothic imagination into the real world. In the history of Philippine cinema, the renowned film series Shake, Rattle, and Roll (1984) became a defining influence. It seemed to magnify traditional gender norms, featuring women falling under the control of either men or the supernatural. The portrayal of objectification and violence against women mirrored how the Philippines, as well as the rest of the world, viewed a woman’s agency in society.

The silver screen had taken this to a new level, showcasing what I would call “patriarchy’s paradox.” This alludes to the two typical character types seen in women in horror. On one hand, the over-raging villainous woman who seeks to bring chaos to society, and on the other, the supposedly kind-hearted and obedient women who condemn the ill behavior of other women, unknowingly contributing to a tradition of inequality and misogyny.

Despite the vastly dichotomic natures of these characters, there is always one fact that prevails: Women have no independent place in the world, fictional or real. The presence of 20th-century female characters was almost always depicted as derivatives of evil, whether that be the crazed or the snitch. The annoyingly enthusiastic or slobbish. The emotional or apathetic.

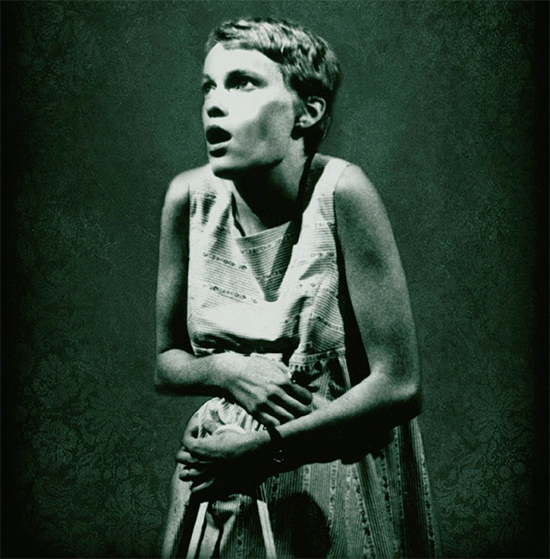

Simultaneously, however, a new wave of feminism caught on, and it was during this second wave that feminism fought fire with fire. Aiming to achieve equality for women in all areas of life, its primary advocacy was to demand autonomy and freedom for women. Films like Rosemary's Baby (1968) and The Stepford Wives (1975) brought unique approaches to raising awareness of social anxieties and political tensions between women and what is expected of them, especially in terms of reproductive autonomy. The horror genre, once known as a misogynistic device to oppress women, became an avenue to express independence to the female character, bringing forth freedom and representation into the narrative.

Now, women in this genre have been acclaimed for their refined and dynamic understanding of fear and panic. The curation of female characters in 21st-century horror films exhibits how lived experiences in patriarchal systems may generate more realistic and thrilling fears, honing the art of subtlety perfected from oppression.

Just like how the third wave of feminism aimed to fuse identity with womanhood, the eerie nature of 21st-century horror coincidentally followed suit. The expansion of a multidimensional character enlarged the scope of nuance in film, heightening the need for women from diverse backgrounds to portray the underlying connotations of terror and unease.

The existence of multidimensional characters in horror illustrates how the audience's deepest fears can be actualized onscreen, as if watching oneself lodged in the depths of a dystopian, bone-chilling reality.

Changing the definition of horror are films like Us, directed by the renowned Jordan Peele in 2019; Huesera: The Bone Woman by Michelle Garza Cervera in 2022; and most recently, The Ritual by David Midell in 2025. Each movie follows the same principle brought about by the newest wave of feminism, cracking the code for 21st-century horror filmmakers.

In Peele’s Us and Garza’s Huesera, the concept of a mother is destroyed, showcasing how the social symbols of comfort and love could just as easily be defaced, forcibly dismantling gender expectations through fright. Lupita Nyong'o and Natalia Solián’s evolutionary portrayals of womanhood in these films inspire a multifaceted approach to the role of women in horror, welcoming the strange monstrosities usually submerged in one’s subconscious. Midell’s The Ritual reinforces this point as it stages a horrific exorcism in a nunnery and foregoes the mainstream hero-priest trope.

This filmic wave has also shed new light on Filipino horror. For instance, ‘Wag Kang Lilingon by Jerry Lopez Sineneng and Quark Henares focuses on the trauma and resilience of the two main female protagonists as they maneuver through a system of social violence and betrayal. The film does not simply define women as victims, but as breadwinners and survivors who remain steadfast and strong amidst their terrifying reality.

In like manner, Bliss by Jerrold Tarog rightfully finds horror in the female experience in the turbulent Philippine entertainment industry. The film’s success proves that authentic and diverse narratives only seem to hike popularity, not deplete them, and the telling of vulnerable experiences makes horror films even more harrowingly realistic.

As scary movies continue to evolve, so too does their reflection of the feminine—a lens that progresses from evil to empowerment, out of the shadows that thread silently in the exclusively patriarchal canvas of film. Contrary to earlier versions of gore and horror, in today’s world, the genre of horror becomes an integral part of the feminist movement, championing complexity and nuance in the definition of femininity. It is true that there needs to be a continued effort to enhance the movement; however, in the most ironic sense, women have embodied the centuries-long tale of being ghouls and goblins, proving that the ugliness of life—in its most subtle or extreme way—is what makes humanity even just a little bit more interesting.