Mothers of revolution and liberty

Mother’s Day is a thoroughly American concept—but when one thinks of the United States’ most famous moms, from Michelle Obama to Barbara Bush, or even Jackie Kennedy, all these ladies were known by their husbands’ last names.

By both Spanish custom and Catholic circumstance, Filipino wives stayed true to the names they were born with; and as a result, the mothers of the Philippine Revolution and our very liberty are remembered to this day by their own names.

Leading the list is, of course, Teodora Alonso, mother to the country’s most beloved hero and 10 of his siblings. Jose Rizal was her seventh child. Teodora bore him when she was 34, and in those days, well past her middle age. She was the guiding light of Rizal’s life, weaning him on tales that would shape his character and no doubt made him a better man. Her sufferings and imprisonment would be seared into Rizal’s young heart and taught him at an early age the meaning of justice withheld.

Teodora would be the steadfast caretaker of his bones until they were taken for proper burial in the Luneta. Rizal’s sisters, Josefina and Trinidad, would also take up the fight for freedom and not shirk from taking the Rizal name. There are records of their presence (along with their older brother Paciano) at the Tejeros Convention, when the torch would be passed from Bonifacio to Aguinaldo. The Rizal sisters, as were their husbands, would be persecuted for being faithful to that name.

Josephine Bracken, on the other hand, would not complete the cycle of motherhood. Her son, who would have taken the name of Rizal’s father, Francisco, was born prematurely, succumbed a few hours later, and was buried on the grounds of their home in exile in Dapitan.

Gregoria de Jesus would suffer a similar plight, giving birth as well to a son who she would name after her husband. The infant boy would tragically not survive to see his first year. Gregoria was, however, the midwife to great causes—nay, the mother to the birth of the Katipunan. Gregoria was helpmate, witness, inspiration to Andres Bonifacio. It was formally called the “Kataastaasang Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan”—the Supreme and Most Noble Society of the Sons of the Country, brothers by a blood oath, who were ready to sacrifice their lives in the pursuit of freedom.

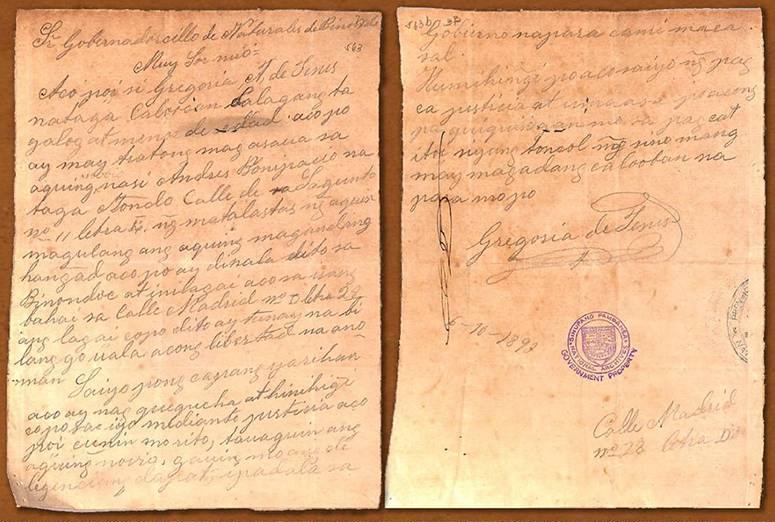

Gregoria, whose 150th birthday anniversary we celebrate this year, was no trophy wife. At age 17, she had fired off a bold letter to the “Gobernadorcillo de los Naturales” of Caloocan, demanding both “justice” and “liberty” to marry her novio Andres Bonifacio. She showed an astounding ease in the way she invoked these concepts, both dangerous and alien for a natural-born or native of Filipinas. They were spelt out in a girlish hand, but make no mistake, her ability to read and write was entirely remarkable as well. It is clear that she had absorbed much from her beloved—apart from these avant-garde ideas, had he also taught her how to read and write? Gregoria importuned that she be rescued from the house on Calle Madrid, No. 22, Letra D, where she had been imprisoned to keep her away from her one, true love. (This astounding document was provided by noted Katipunan scholar Dr. Jim Richardson.)

It was love at first sight, after all, for Bonifacio who first clapped his eyes on Gregoria as a muse of the town Santacruzan. May would always be a momentous time for Gregoria. It would be the month that she would meet her husband—but also in the dark days of 1897, it would also be the month that she would lose him. She would mark her 22nd birthday on May 9th, and live to see the last day on earth of her husband the day after, on the 10th. They would thus be together just five years, both birthing the most tumultuous first age of the Revolution.

Emilio Jacinto, Bonifacio’s closest friend, would leave behind not only a legacy of poetic political writings, but also a woman and mother-to-be—reportedly visibly pregnant when photographed by his bier. She would later be identified as Catalina de Jesus, at least in some records. Was she a distant relation of the intrepid Gregoria? (The local historians of Caloocan would have it that way, since Jacinto and Gregoria were exactly the same age. Mr. Richardson has seen some records, however, that also name her Catalina de la Cruz, but he adds, “We can safely assume she did not take the name Jacinto.”) Emilio’s mother is still remembered. Her name was Josefa Dizon.

There are many more famous and important mothers in Philippine history—Aguinaldo’s own, Trinidad Famy, for one. (Emilio was also her seventh son.)

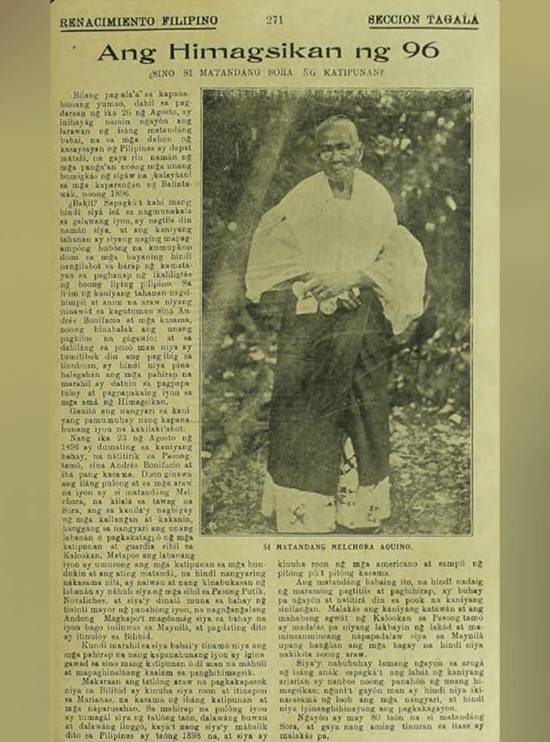

But perhaps the most emblematic of motherhood was Melchora Aquino, the “Tandang Sora” who gave generously to Bonifacio’s army. She was married to Don Fulgencio Ramos and in 1896, “opened her ample bodega to more than a thousand Katipuneros, emptying it of 100 cavans of rice, and all her cattle, carabaos, chickens and pigs.” Like a true mother, she stopped at nothing to feed the children of the Revolution as if they were her own.

Slowly but surely, perhaps with the coming of the puritanical Americans, Filipinas began to take up their husbands’ last names. Marcela Agoncillo, mother of the Philippine flag, was no longer Marcela Mariño but Mrs. Felipe Agoncillo. Josefa Llanes, mother of the Girl Scouts of the Philippines and war heroine, would be Mrs. Escoda.

To be sure, Philippine law allows married women to keep their maiden names. It’s a tradition that’s certainly worth returning to.