The national pantry on trial

We sometimes define ourselves by what we consume and what we refuse to let go of.

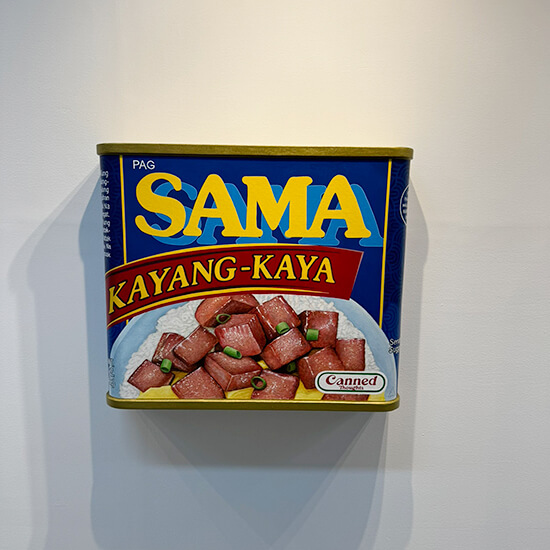

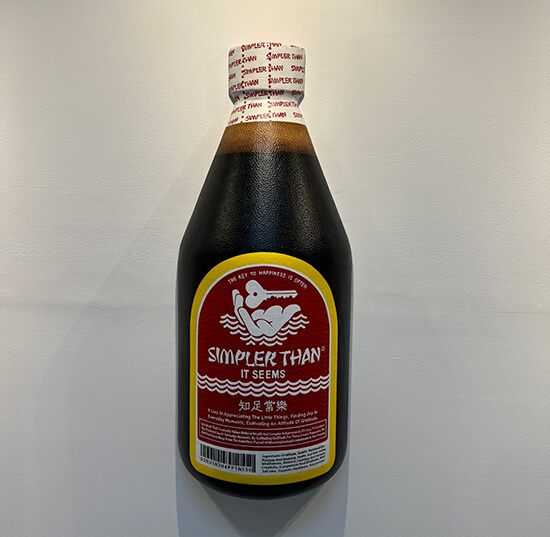

Walk into any Filipino kitchen and you will find a pantry that functions as a crowded census of our anxieties and our appetites. Bottles of liver sauce and cans of spiced ham sit like relatives in a cramped house, reflecting a history of typhoon seasons and holiday excess. Every household believes its arrangement is natural, even when it reveals the fear of running out.

Carlo Tanseco comes from a world of measurement and architectural restraint, a background that seems at odds with the messy, loud reality of Philippine life. Yet his work thrives in that tension. By taking the most mundane objects of our daily survival and rendering them with surgical discipline in his Ibang Label series, he creates a space where our habits are finally forced to answer for themselves.

When Carlo enlarges these everyday items and brings them into the gallery, he touches a nerve because food in this country rarely stays within the limits of hunger. His work begins with recognition. “These are objects most Filipinos know instinctively, almost without thought,” he says. The act of enlarging them interrupts that automatic response and creates a pause where memory and personal history can surface. He speaks of words and phrases on the works as gentle cues that guide recollection toward affirmation. That explanation shows his respect for the viewer’s own store of memories. Carlo does not supply the story and instead sets the stage for it to arrive.

Filipino conversations begin and end with food. Someone remembers a grandmother through a brand of sardines. Someone measures payday by the ability to buy imported ham. Even the sari-sari store becomes a theater of longing where a child points at a bright label and learns early how desire gets priced. In Carlo’s giant bottles and cans, that world is contained. They carry birthdays, brownouts, road trips, and the small pride of serving guests a recognizable brand. The works feel autobiographical without turning into confession, and that balance matters in a culture where personal stories often double as social currency.

Carlo keeps his own supply of lechon liver sauce in his tuktuk in Siargao. A man who travels with sauce travels with a baseline for pleasure, and he admits that these preferences enter the work. The paintings and objects trace a life where taste becomes a diary written in condiments and packaging. I recognize that impulse because many of us carry home in flavors long after we move away from it.

Humor enters Carlo’s practice with a light step. I ask him when that lightness corners a viewer into seeing what they might ignore. “I don’t think of humor as a trap,” he answers. “It’s more of an entry point.” These products are tied to comfort and shared experience. Their familiarity, according to him, lowers defenses. To him, the lightness disarms cynicism and, once a viewer is open, the work can introduce ideas of hope, care, and possibility without force.

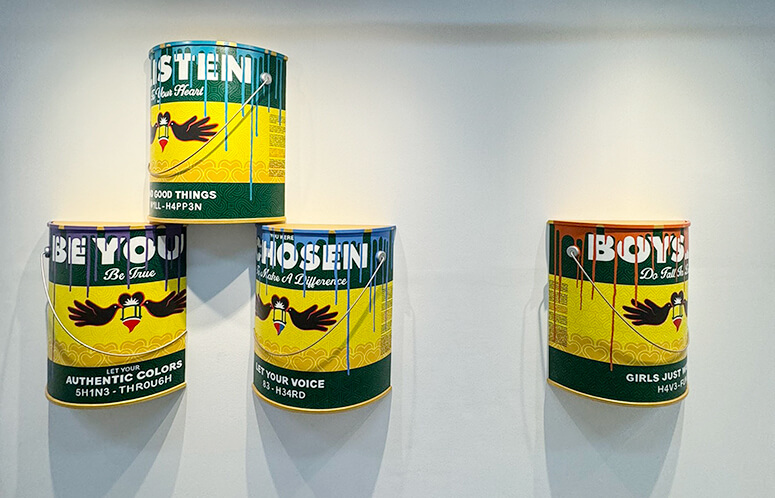

Carlo’s training in architecture shows in the monumental pencils and the attention to proportion. Measurement, scale and control shape how the works occupy space. In a country where systems often feel loose and consequences feel negotiable, discipline inside an artwork carries its own message. Discipline in art, according to him, cannot replace justice or accountability, but it can assert a standard grounded in intention and responsibility. Within that stance lies a refusal to let disorder dictate every language available to us.

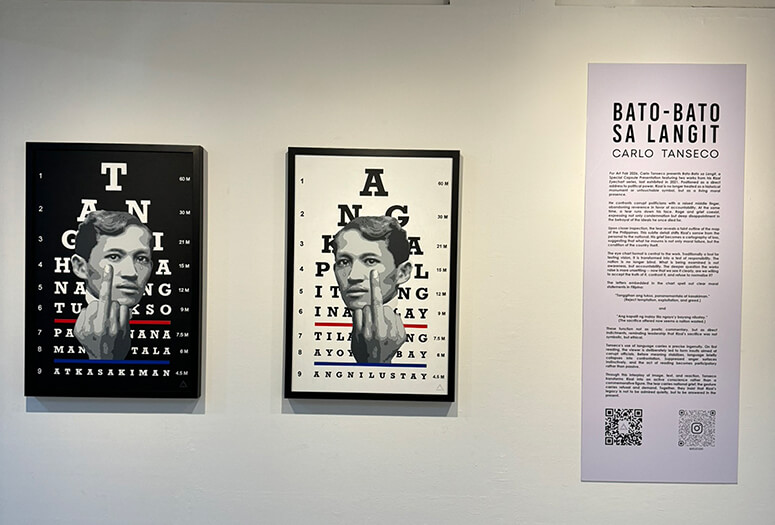

Then there is José Rizal, revived in “Bato-bato Sa Langit,” a capsule series that refuses the textbook treatment. Every Filipino grows up with a Rizal who looks composed in textbooks, a hero who feels complete and sealed. Carlo’s Rizal cries and raises a middle finger, and that image alone short-circuits the usual reverence. I ask him what this flawed and emotional Rizal makes possible for young Filipinos. “A polished Rizal asks for admiration, not engagement,” he replies. Allowing Rizal to be emotional restores friction and makes space for doubt, disagreement, even anger.

The eye chart format draws from Rizal’s training as an ophthalmologist. Carlo identifies a misplacement of pride in the Filipino psyche. We celebrate resilience in ways that inadvertently normalize poor systems, poor governance, and stagnant standards. There is a tendency to welcome praise while resisting the very criticism that leads to growth. This imbalance clouds our collective vision, and Carlo insists that learning to see ourselves without defensiveness is the only path toward progress.

In the Rizal Eyechart works, a tear runs down Rizal’s face, tracing the faint outline of the Philippines. The image turns grief into a map and gives sorrow a geography. The letters in the charts land as instructions and verdicts at once. The viewer reads, stumbles, and rereads, caught in a process where language becomes a direct collision. The raised finger directs anger toward corrupt leadership, and the tear pulls the nation into that emotion.

as literal vessels for virtue, using graphic clarity to drip instructions of hope and authenticity onto a landscape often defined by negotiable consequences.

Art fairs run on saturation, with every wall competing for a second look. Of his participation in the just-concluded Art Fair Philippines 2026, Carlo says, “I don’t try to compete with the spectacle.” He relies instead on a disciplined economy of form. Where other works might try to overwhelm the senses through sheer volume, his pieces function as a clearing. He trusts that a well-placed fixation can disrupt the habit of mindless looking and turn a casual passerby into a witness.

There is a deceptive ease to the way these images move through the world. They are built to be shared, designed with a graphic clarity that thrives in the rapid stream of a digital feed. Yet this accessibility is a camouflage. Carlo uses the smile of recognition as a decoy, drawing the viewer in with the comfort of a familiar brand or a clever pun before the underlying sharp edges of the work take hold. You enter through the door of the domestic, only to find yourself caught in a confrontation about governance and the cost of national pride. The work invites a longer stay and then asks for a response that the casual viewer didn’t see coming.

Carlo is under no illusion that a painting can do the work of a court ruling or a policy shift. His art does not offer a rescue. It provides a blueprint for a different kind of vision. He acknowledges the limits of the canvas and keeps the work tethered to the world outside the gallery. He understands that an eye chart is only a piece of paper until someone chooses to read it. Once the vision is corrected, the responsibility to act belongs entirely to the person who has walked away.