The Filipino Flex at Singapore Art Fair

Despite being up against such thousand-pound gorillas as Indonesia and Singapore—made even more muscular by each government’s backing in the gazillions of dollars—the Philippines continues to be the No. 1 art market in Southeast Asia.

Indeed, across all Asian countries, the Philippines comes in at No. 5. That’s not too shabby, considering that China, Japan, India, and South Korea take up the slots ahead of it. So said a specialized report on the region released in the “Asian Pivot” in late 2024 that tracks art world trends often under-rated by Western media. The Asian Pivot is co-founded by London-based Vivienne Chow of Artnet, the world’s most-read art media platform with over 200 million views.

That said, Asia is clearly the place to be, and Art SG is the gold standard in terms of scope and logistics among the region’s art fairs. One of its main advantages is that it is embedded in the carefully curated environment that is Singapore. The entire experience is a seamless, First World flow from touchdown at Changi airport to the drive down its wide boulevards lined with bougainvillea and lush fern trees to the soaring, luxurious proportions of the Marina Bay Sands Expo and Convention Center.

Setting the stage was a spectacular opening night at the National Gallery of Singapore, its spaces outlined in towering pink lights and sharp tableaus. Guests could tour the magical exhibition of Impressionist masters on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, for free. A dizzying array of Degas, Renoir, and 17 dazzling Monets, not to mention many iconic masterpieces, pre-conditioned the viewers for the overwhelming art week ahead.

This year’s SEA Focus, intended for emerging artists and galleries in the region, was folded into the cavernous art fair venue, adding gravitas to what had been a previously underground series of exhibitions. Kristoffer Ardeña, on the ArtInformal roster, was among the most striking: micro-video installations juxtaposed with portraits of Filipino superheroes, Bonifacio and Rizal. He wrapped it all up with the haunting last words in faded ink, “Ang mamatay ng dahil sa iyo,” of the Philippine national anthem. Ardeña pointed out that the disappearing words represent the values people today forget as easily as if they were written on Snapchat. (The same could be said of the flood control scandals that now feel a million miles away.)

The main event of Art SG featured some 100 galleries from around the world, intended to position this island city as the premier portal for art, not just in Asia but worldwide. Thus, there were players from every continent, including biggies such as White Cube in London and Lehmann Maupin in New York, as well as galleries further afield.

To pick out a very few, there was Joseph Gergel of the Kó artspace in Lagos, Nigeria, who announced a sale to an international museum, a deal closed in Singapore. It’s a striking work by Obiora Udechukwu titled “Blue Figures (Refugees).” Its fiery account of the Biafran famine eerily resembled the Filipino neo-realist wraiths of H.R. Ocampo, depicting the desperation of Manila in 1945.

Sabina Blumenkranz of the In the Gallery outfit of both Copenhagen and Palma de Mallorca showed large-format photographs of tropical edens, while Patel Brown of Toronto showed dancing women and durian fruit. All these newbies echoed a desire to dip their toes in the Asian market and find out what all the fuss was about.

Patel Brown was best rewarded: it showcased the work of a Filipina, Marigold Santos, a child of the Philippine diaspora, as she searches for her identity. Evocatively, she found it in the expression of dozens of “aswang” (witches), in languorous poses. Co-founder Gareth Brown-Jowett said that he had been immediately drawn to Santos’ work. His instincts paid off, as Filipino collectors snapped up almost all of her delicate drawings—even before she was named most outstanding emerging artist of Art SG. Marigold bested 37 other artists in the field and received a fat check for $10,000, sponsored by the Swiss banking behemoth UBS, long-time partner and supporter of the fair.

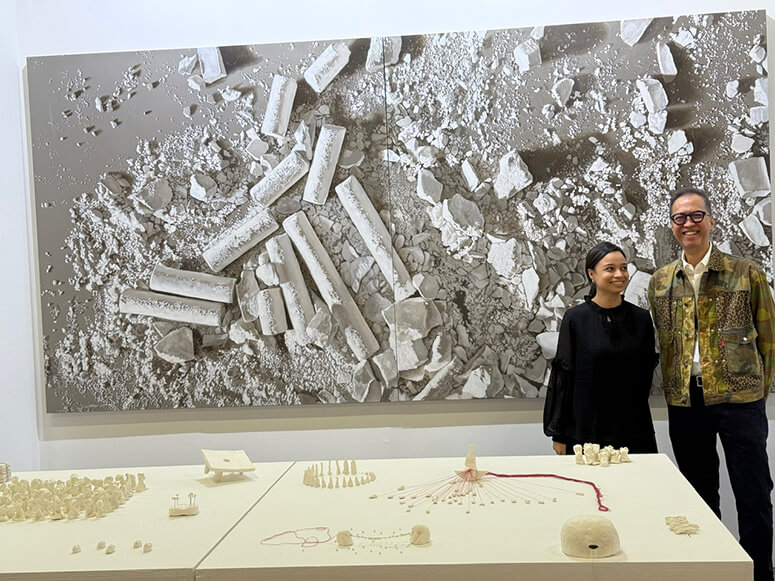

The Filipino galleries that had flown in from Manila were clearly up for any challenge. Drawing Room founder Jun Villalon said his gallery had been a happy member of the ecosystem since Art SG began in 2023. Villalon gave pride of place to another young Filipina artist who also combined a 3D installation with a solid, meat-and-potatoes work in the old-fashioned medium of oil on canvas. With the name of a 13th-century Byzantine martyr, Chelsea Theodosis, this artist prefers to work with another vanishing medium—and subject—the powdery element of chalk. Entitled “Chalk in a Shrine,” this massive work stopped the foot traffic and attracted several inquiries. (The Filipino obsession with the temporary and the forgettable would make an interesting psychological study.)

Tina Fernandez of ArtInformal believes that attending international art fairs is more about building relationships and less about minding the bottom line. To that end, she flew in a slew of artists; among them were Zean Cabangis (who presented fascinating snapshots of the war between the manmade and Mother Nature—which resonates with the current battle between infrastructure and swollen rivers ), Monica Delgado (handpainted ceramic apples for tempting any Adam), and Winnie Go (a wall of sacred images). Pope Bacay, Jigger Cruz, Johanna Helmuth and Raena Abella were also well represented.

Filipinos also dominated in an off-site show that made it to the Straits Times’ top three must-sees of the fair. Titled “Isang Dipang Langit: Fragments of Memory, Fields of Now,” it was curated by the Korean Dong Jo Chang, who certainly knows his Filipino artists—and social realists. He selected a who’s who in contemporary Filipino art for a show for the gallery he founded, Columns, Seoul. Referencing an Amado V. Hernandez poem on imprisonment and the true meaning of freedom, it was suitably set in Tanjong Pagar Distripark, a grungy complex of warehouses on the docks that somehow reminded him of Hernandez’s sliver of sky.

There, Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan presented tiny metal houses on wheelbarrows; Pete Jimenez, a series of rusted, bomb-like machine parts strung together; Elaine Navas, a sea of kilometric blue. There were installations hanging from the ceiling (plastic blowfish by Leeroy New, a bubblewrap-ballgown also by him and worn by an itinerant model, and another, a heap of fluff, an effigy of Charlie Brown’s dust magnet, “Pig Pen”). Most moving were wall-sized portraits of Pinoy migrant workers by Oca Villamiel. Filipino art tends not to be menacing or disturbing; even enfant terrible Manuel Ocampo hung up his spurs for this one and showed multiple Daffy Ducks. The other artists included Dominic Mangila, Russ Ligtas, and Eisa Jocson.

Now, what exactly is it about an international stage that brings out the best in Filipinos? It’s both inspiring and perplexing that it is Singapore that provides the backdrop for some of the Philippines’ most interesting art and its biggest flex.

Patrick Flores, chief curator of the Singapore National Gallery and eminence grise of some of the region’s most exciting shows, has many of the answers. In fact, he launched a 400-page volume on art titled Sensible Forms: Essays in time for the art fair at the Philippine embassy. Present were Ambassador Medardo Macaraig, top collectors Lito and Kim Camacho, and Tina Colayco of the M.

The secret sauce will always lie in Filipino talent that knows no boundaries, irrepressible and unbridled, that has bowed to no master since the time of the footbridges that crossed Asia, that could never be silenced by any of its many different colonial masters.

We can always expect Filipinos to unapologetically continue to tell their own story and march to their own drum, even if they must say it and play it in other people’s houses.