Of mountains and mysteries at Venice Biennale

VENICE, Italy — There’s a moment during the looped video shown at the Philippine Pavilion of this year’s Venice Biennale, “Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito / Waiting just behind the curtain of this age” (featuring artworks by Mark Salvatus and curated by Carlos Quijon Jr.), that seems to encapsulate the artist’s approach: a brass instrument in a forest, shyly peeking out from behind a tree like an alien bird beak, then retreating just as shyly (slyly?) from view.

“In a way, it’s kind of like the spirits are like that,” Salvatus says of his native Lucban, where he grew up gazing at mystical Mt. Banahaw from his boyhood window. “They’re inserting their presence in our lives, like they’re just there, but you don’t feel them. It kind of makes you feel, ‘Ah, okay, there’s something…’”

A mystical mountain retreat. A Filipino folk hero in the form of Hermano Puli. Healing energies and massages. Maybe even UFOs.

Mt. Banahaw is the backdrop for “Curtain of this age,” and Puli—whose pre-revolutionary Cofradia inspired a grassroots spiritual movement outside the Church, and whose final enigmatic statement provides the show’s title—didn’t exactly change history; he inserted himself in sly ways, like that brass instrument.

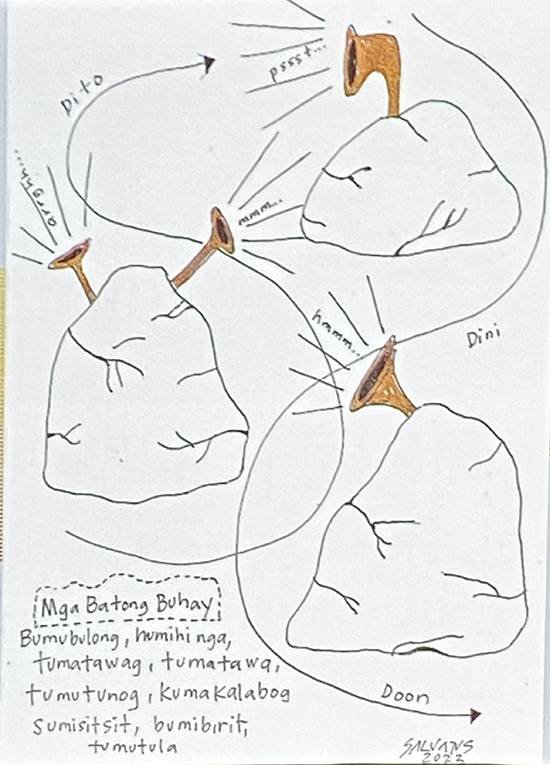

Early concept drawing by artist Mark Salvatus

“So, yeah, this idea of small movement,” says Salvatus. “Hermano Puli didn’t create a big movement, but it impacted history, because Jose Rizal was inspired; he didn’t even meet him, just through stories.”

Psst!

Listen: That’s the sound of the Philippines, calling out to visitors at this year’s Biennale. Aside from human sounds (“Psst!” or “Hmm...”), birdsong, whistles, trickling water and occasional trumpet bleats emerge. Swathing the space are sheer curtains, leading you… somewhere. Mammoth boulders embedded with marching band instruments surround a central screen, where images of Mt. Banahaw and its ephemera loop endlessly, along with ambient sounds of nature. On its closing day, the Philippine Pavilion rang up some 9,000 visitors.

Poo-tee-weet?

Listen: The Philippines is a pilgrim’s journey, unstuck in time. Out here in the Arsenale ozone between noisy Ireland and Lebanon, Salvatus and Quijon imagine a new way of viewing our place in the timeline.

“We didn’t want to compete with all these stimuli,” says Quijon of the other hurly-burly outposts at Arsenale. “This is like a place to rest, a place to stop.” Nonlinear. Unstuck in time.

“We started with Mark’s story growing up there, and uncovered a lot of mystical stories around the mountain. One is that people claim they’ve seen UFOs stopping by to refuel.” (Refuel on what? we’re led to ask.) Salvatus himself admits to seeing lights dancing in the sky as a high schooler. There are cults attracted to the mountain, waiting for the Second Coming of Christ; it’s also where communists hid from the state. And it’s a place with a personal connection to Salvatus—his grandfather’s archival photos, a Lucban theme song written by his lolo, and his family connection to the Manila-Band, a marching troupe that played around Asia and the world way back when. Themes he’s explored in past exhibits like 2017’s “Museo Ng Banahaw.” All ephemera connected with the mountain, presented in a free-associative manner, “smuggling” and inserting minor histories into a traditional museum context. Salvatus calls such artworks “Salvage Projects.”

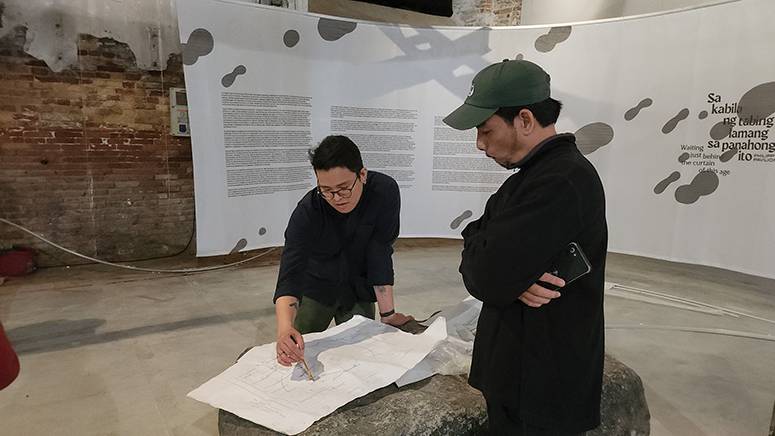

For Quijon, who’s worked with the artist on past shows, curating meant taking the Mt. Banahaw framework to a bigger world stage. “We started thinking about the idea of ‘staging’: how do we create a pavilion that is essentially a stage? We leaned into this idea that you go from one place to the next.” For one thing, there’s no effort to conceal the artificial seams on the fiberglass boulders that have been shipped from Manila and reassembled at Arsenale. For another, you can enter from either end of the exhibit, wander here or there. There’s movement, as in a play, but it’s up to you. The exposed beams and natural light emphasize the artificiality. The central video shot by Salvatus and crew features local musicians decked out in tribal gear, “playing” broken branches and leaves as brass sounds emanate. Salvatus found a local high school dance team on Facebook who—coincidentally—dressed in alien lights and costumes and had them recreate UFOs dancing in the night skies in his video.

Hidden histories, inserting themselves in the narrative. It’s been Salvatus’s practice since he graduated UST as an advertising major and switched to street art. He’s drawn to souvenirs, and people’s connection with them. “When you keep souvenir items, you want to extend the time you traveled to a place,” he says in the show’s brochure. “I am curious about how people—especially my family—have created a world within a private space by gathering things as signals of desires. Be they vinyl records, photographs, or stories, this micro-universe could be connected to a larger context: the history of the Philippines and of the world… l work with materials that found me. I am interested in materials and things that have insignificant value.”

At the same time, Quijon wanted to open up Salvatus’ work to a world-class pavilion. “We discussed how to think about spectacle, how do we create a work for the pavilion that extends your practice and interests organically? I wanted it to also mark a certain stage of his practice—so it’s not too hermetic, not too self-absorbed. It can be approached in many ways.”

Similar to Mt. Banahaw itself. “Out my window, I only see one view of it. But if you’re in another city, you see another view. It’s also different when you climb the mountain: you no longer see the mountain, you’re already there. So for me, I’m just one of these viewers that interprets this.”

Like Donovan once sang: “First there is a mountain, then there is no mountain; then there is...”;

Both Salvatus and Quijon are interested in nonlinearity, the appeal of reading history from different angles, different perspectives. Once, when Salvatus bought his uncle’s old computer, he inherited a trove of photos from his uncle’s days working as a seaman. They formed the context of “Souvenirs,” a 2013 photo exhibit of landscapes paired with images of human labor and effort. In “Wrapped: Traces Project” (2017), he invited participants to trace personal items on a wall; then he “wrapped” the outlines with pencil, like mummified memories. “I was interested in the things people carried around,” he says of that show. “It’s tied to the idea of collecting, of collective memory.”

And to the things that tie us together. “Foreigners Everywhere” was this year’s Biennale theme. “It’s an interesting proposition,” notes Quijon. “We started thinking, if foreigners are everywhere, where are the locals?” Also: “When you don’t have a choice to come back, how do you imagine the nation?”

The Philippine Pavilion invited visitors to think about their place as human, or as Filipino, or as both. This year, in lieu of a closing ceremony, the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) and Philippine Arts in Venice Biennale (PAVB) tried something different: an audacious weeklong road trip meeting Filipino communities throughout Italy. Called the “Lakaran Lecture-Workshop Series,” it would take the artist, curator, media and organizing members of PAVB onto the ground, outside Venice, to try to elicit a deeper understanding of Filipino connectedness through sharing personal objects and stories. (More about this in an upcoming article.)

“It’s an extension of the Philippine pavilion, but not directly,” says Salvatus. “For this, we didn’t want to have this hierarchy.” The “Lakaran” flips the script on a museum, allowing the visitors to create their own meaning. Just as thousands did, wandering through the birdcalls and coughs and tuba bursts in the Philippine Pavilion.

“Sometimes we need to be confused,” suggests Salvatus. “But I want to confuse better, rather than to tell everything. Confusion is something that is also liberating, because you are the one who will think, not the other way around. I want to understand by misunderstanding.”

Poo-tee-weet?

* * *

The Philippine Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, “Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito / Waiting just behind the curtain of this age,” closed Nov. 24. It will have a homecoming presentation in the Philippines in 2025.

The Philippine participation in the 60th La Biennale di Venezia is a collaborative undertaking of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), and the Office of Senate President Pro Tempore Loren Legarda. For information, visit philartsvenicebiennale.org. See updates on Facebook and Instagram via @philartsvenice.