Paint, over-paint, repaint, restore?

Wall paintings are perhaps the oldest known paintings.

Where preserving painted wall decorations and murals are concerned, the intent of repairing a damaged original is, without question, always good. Whether it is to preserve the original image that has been iconic for generations, or whether it is to improve on the original by creating a similar but different image, or to totally change what was originally there, the aspiration is always for the better. However, where preservation and conservation are concerned, altering the original is never acceptable. And here, the confusion and contention for preservation lies.

Unlike canvas paintings that are often signed and dated by the artist, most—if not all—wall paintings are left unsigned. Most wall paintings are rendered by nameless artisans, unless commissioned from a named artist. What mostly gives an unsigned wall painting value is its authenticity based on its historical value and age.

The controversial Altamira cave in Spain with its prehistoric charcoal and polychrome animal drawings is known to be the earliest discovery in 1868. Supposedly done during the Upper Paleolithic, roughly 36,000 years ago, its authenticity did not survive experts’ scrutiny and assessment after other prehistoric drawings were found, the reason being that “prehistoric human beings lacked sufficient ability for abstract thought.”

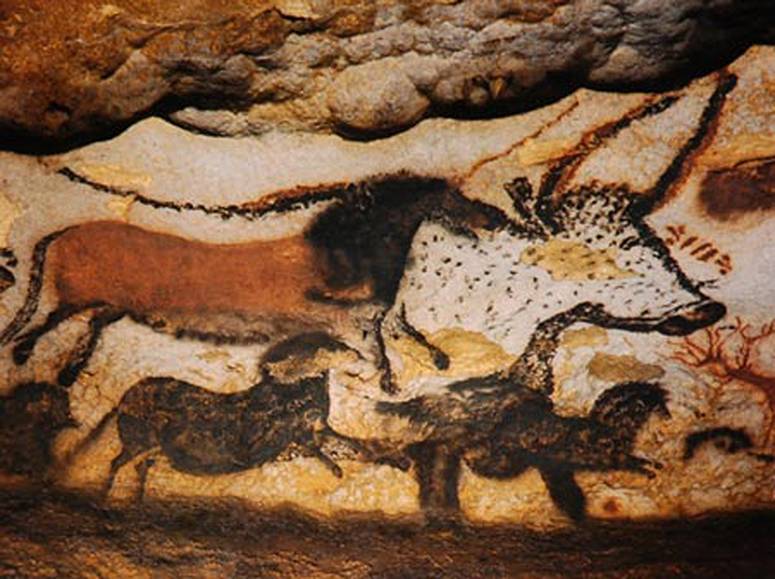

Extensive research followed until the evidence of non-authenticity accumulated and could no longer be rejected. Nonetheless, Altamira was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The early cave drawing that passed the scrutiny of experts was the Lascaux Grotto cave in France, with a series of prehistoric drawings which were painted and engraved, numbering about 600 figures that were deemed authentic, as witnessed by the style and rendering of the drawings that dated approximately 17,000 years old. In 1979, the grotto and its wall drawings were given a UNESCO World Heritage citation.

In the Philippines, the oldest known church paintings are found in San Agustin Church. Its present structure was constructed using adobe stone in 1586 and completed in 1607 by the architect Juan Macias. Although the church survived the strongest earthquake endured by Manila in the 16th and 17th centuries, it was not spared partial destruction during the Battle of Manila in 1945. It was one of the structures left standing when Manila was practically flattened to the ground by Japanese and American shelling. Compromised were the beautiful, elegant trompe l’oeil wall and ceiling decorations commissioned in 1845 from two Italian visiting scenographers, Cesare Alberoni and Giovanni Dibella, by the Spanish architect Luciano Oliver.

The term “trompe l’oeil” literally means “fool the eye,” which gives the painted architectural details a three-dimensional impression of religious symbols, faux pillars, animal and floral motifs. Completed in 15 months with their Filipino assistants, Alberoni and Dibella were paid a then-hefty sum of P6,000 with an additional P2,000 to hasten its completion. Since then, these decorations have deteriorated due to age cracks, salt encrustations and moisture seepage, requiring vigilant, periodic restoration.

American businessman and philanthropist Brad S. Smith succinctly noted, “Good intentions often get muddled with very complex execution.” For some cases in the restoration and preservation of wall paintings, what he said couldn’t be truer.

Churches, apart from heritage family homes, have been the canvas for painted decorative designs and murals. Wall paintings, which are usually large ones strategically positioned in architectural niches, are referred to as “mural paintings.” Early renditions were done in the fresco technique (i.e., “buon fresco” or true fresco, which requires a “wet on wet” painting technique, as seen in the work of Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel). In present-day parlance, the terms “fresco” and “mural” are often interchanged or misused. In the case of The San Agustin Church, artists Dibella and Alberoni resorted to the “a secco” (dry) technique, owing to the lack of materials required for a fresco. While the aesthetic of an “a secco” mural may be like a true fresco where pigments penetrate through the surface, the pigment penetration on a dry surface is merely superficial.

When the 7.2 earthquake hit Bohol on October 15, 2013, 10 of their main churches, all known to have ceiling paintings, fell, exposing that most of the paintings were rendered on iron sheets.

A scientific analysis of the pigments used was done by Gracile Roxas, formerly with the National Historical Commission, and Dong Hyeok Moon of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, South Korea. “It was observed that different types of grounds were applied on different types of surfaces. Moreover, organic pigments were found in combination with white extender materials. Microscopic examination also revealed alterations in the artworks, such as the overpaint layer found in the samples from Baclayon Church cornice and the imitation metal-leaf layers applied over the original gilt surface in the Loay Church retablo. In short, these did not remain respectful to the original.”

Nevertheless, these were restored, although authenticity may now be disputable.

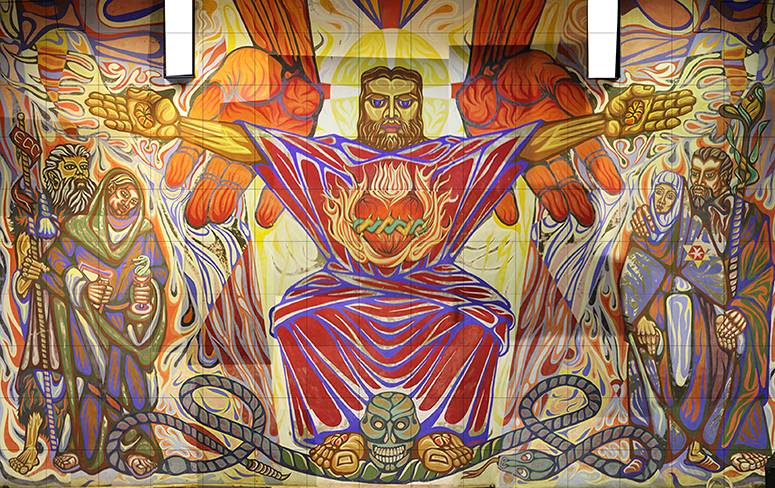

Restoring a wall painting requires tedious assessment for deterioration, since the wall, which is the painting’s canvas, is part of the structure. Since these unsigned wall paintings are often publicly displayed, the itch for a concerned individual to repair a delaminated wall painting on his own can be tempting. In the St. Joseph the Worker chapel in Victorias, Negros Occidental, the 60-sqm mural, “The Last Judgement,” aka “The Angry Christ,” was found to have been painted over in tempera paint, which tends to powder as it deteriorates. A yellow portion close to the face of Christ delaminated and powdered, and eventually colored the face of Christ a jaundiced yellow.

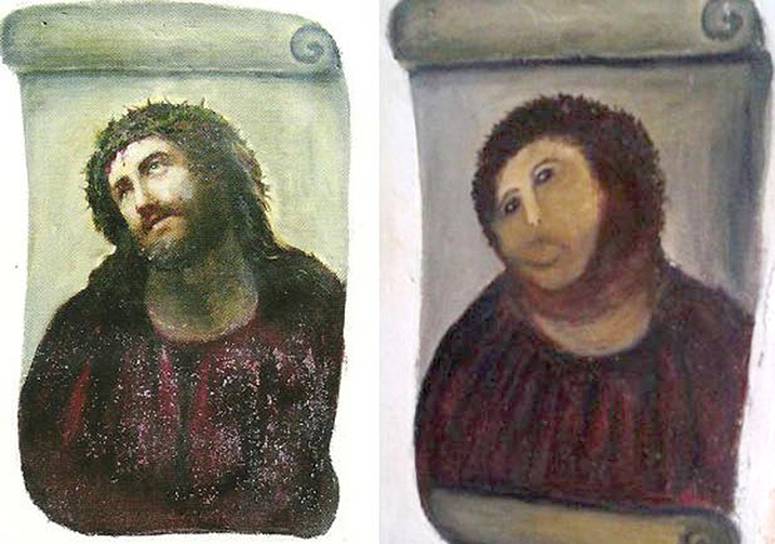

Perhaps the most recent, well-intentioned “restoration” was also the face of Christ, devotedly “restored” by an untrained amateur artist, Cecilia Gimenez in 2012. The fresco, called “Ecce Homo,” (Behold the Man) located at the Sanctuary of Mercy church in Borja, Zaragoza, in Spain was in an advanced state of deterioration. Gimenez’s intervention transformed the gentle yet suffering face of Christ to a face like a monkey’s, thus people renamed it “Ecce Mono” (Behold the Monkey). Because of the global uproar and attention paid to the failed restoration, the chapel became a tourist attraction for 57,000 visitors in March 2016, and donations to the church generated as much as 50,000 euros, which helped fund a home for retirees. Gimenez gets a share of the royalties, which she uses to help muscular dystrophy clinics because her own son suffers from that condition.

While Gimenez’s well-intentioned but failed restoration attempt has an ongoing happy ending, it doesn’t always hold true for badly restored wall paintings, sometimes sadly executed by trained conservators who may tend to “improve” a painting by including their own signature strokes or worse, repainting the mural, thus totally disrespecting the original and lessening its value. American businessman and philanthropist Brad S. Smith succinctly noted, “Good intentions often get muddled with very complex execution.” For some cases in the restoration and preservation of wall paintings, what he said couldn’t be truer.