Fernando Zobel at The Prado: Painting the future by seeing the past

MADRID — “Let me tell you something,” declares Georgina Padilla Zobel. “Never, never in his wildest dreams did Tío Fernando think that one day he would have an exhibit in the Prado. He loved the Prado, he admired the Prado so much, he would come here very often, but for his work to be exhibited here, it never would have crossed his mind.”

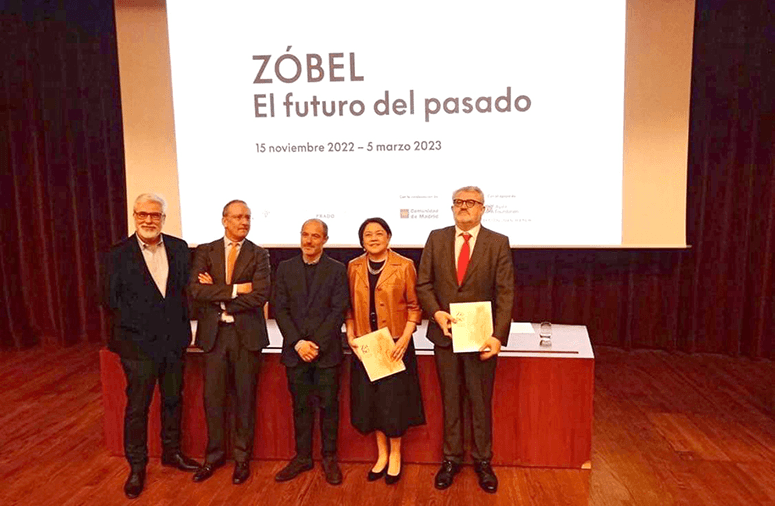

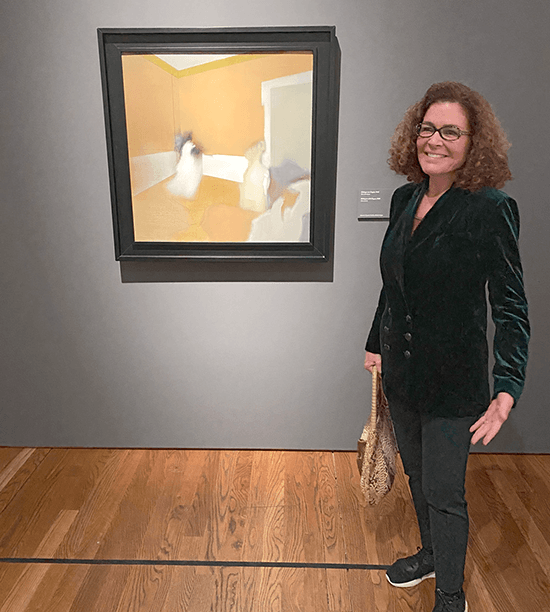

She emphasized this at the preview for “Zobel El Futuro del Pasado,” or “Zobel The Future of the Past,” the day before the exhibition opened to the public. Running until March 5, 2023 at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, the show is a major survey of the work of Fernando Zobel, a vital figure in Spanish art of the second half of the 20th century. He also played an important role in Philippine modern art. This exhibit offers a reassessment of his work, seen through 42 paintings, 51 sketchbooks, and 85 drawings, in one of the most important museums in the world; a fitting—perhaps even overdue—tribute.

Exhibition viewers feel the love for the Prado that Padilla Zobel mentions run through the entire show, an adulation and estimation for the old masters, deities of painting that informed Fernando Zobel’s work.

“When I was appointed a few years ago,” says Miguel Falomir Faus, director of the Prado, “I began to plan what was going to be the relationship of an old masters museum such as the Prado with contemporary art. We are not a contemporary art museum but we cannot ignore those contemporary artists who too were interested in the Prado. Fernando Zobel is such an artist.”

Felipe Pereda, Fernando Zobel de Ayala professor of Spanish Art at Harvard University, and Manuel Fontán del Junco, director of Museums and Exhibitions of Fundacion Juan March, serve as curators for this show. It was Pereda, a close friend of the museum director, who presented the concept to the Prado, born out of a seminar he conducted at Harvard. He had been mulling over plans for just such an exhibit since 2015.

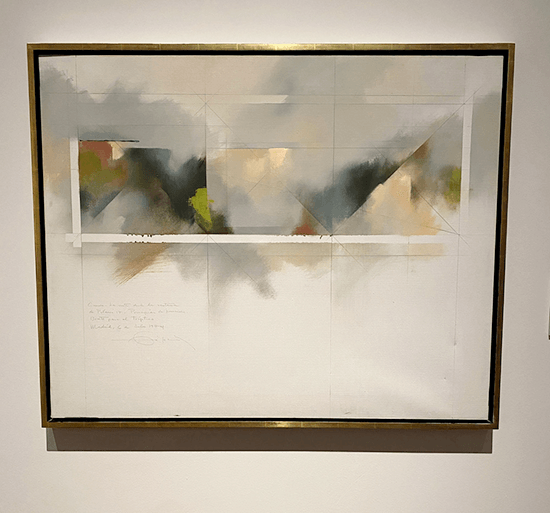

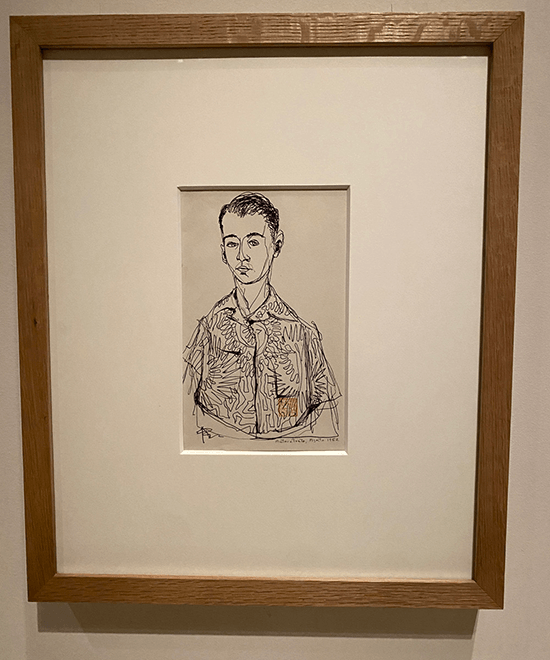

The curators approach the exhibit in two ways: the first by taking viewers through Zobel’s artistic process, as seen through his writings and drawings from his sketchbooks; the second by situating this artistic process through the phases of a life lived in three continents: born and raised in Asia, specifically, Manila; educated in North America, at Harvard; and the final phase as an artist and art patron in Europe, in Cuenca, Spain.

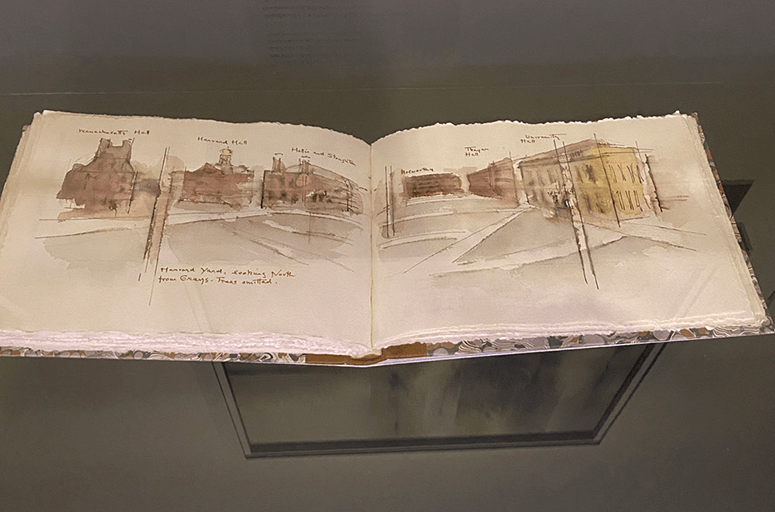

The sketchbooks lie at the heart of the exhibition, figuring as prominently as they did in the artist’s life. By several accounts, Zobel carried a sketchbook with him wherever he went. They numbered 150 at the time of his death in 1984. Fashioned from pages of a type of paper that would faithfully retain watercolor first sourced from Japan, then from Venice, and bound specially for him, the sketchbooks serve as journals, wonderful windows into Zobel’s creativity; one can ruminate on them as art pieces on their own. They contain his drawings, not just mere scribbles done at the spur of the moment, but impressions and distillations mostly of works by the masters, a large number of them from the Prado’s collection. He would include color swatches, photos, very often his own reflections eruditely written, quotes from artists, well-known authors, philosophers, poetry. The sketchbooks are numbered, neat, ordered, hinting at the discipline that would characterize his paintings, especially those done when he embraced abstraction. One could describe each page as a sort of mood board—but on steroids, for all that they contain.

Running until March 5, 2023 at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, the show is a major survey of the work of Fernando Zobel, a vital figure in Spanish art of the second half of the 20th century.

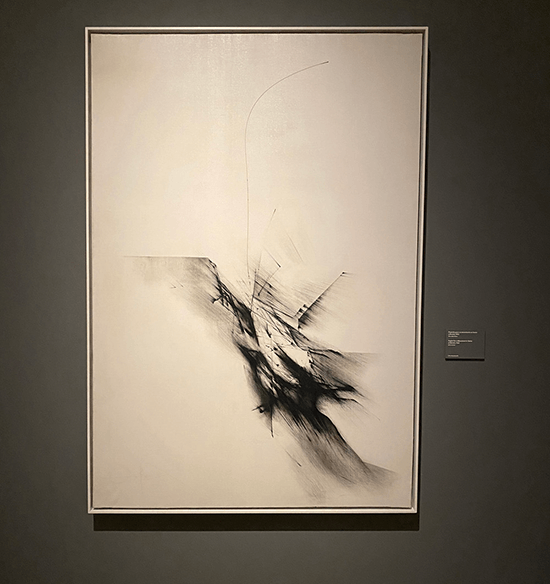

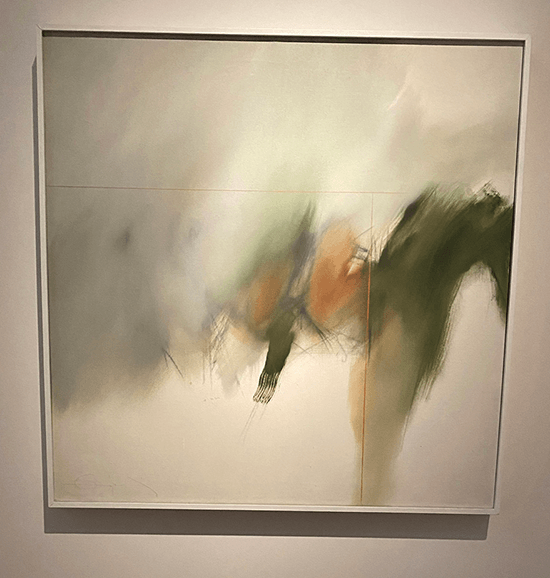

The curators have striven to get the viewers to understand that these sketchbooks are key to a deeper appreciation and respect for Zobel’s work. They emphasize that Zobel looked at and saw the old masters through his drawings. Zobel called many of his paintings dialogos, conversations. And indeed, looking across his sketchbooks and his finished work, the viewer comes to understand that each painting or print or collage that Zobel completed is a discussion, debate, tête-á-tête, communion between himself and the work of these great artists. Yet, he wasn’t just interpreting that work or paying homage to the original artist. Through his own paintings, he propelled the original work of art into a future that he thought they ought to have, a future he created by pulling on an emotion he retained from these inner conversations, paring them down to their essences. Hence, the exhibition’s title, “The Future of the Past.”

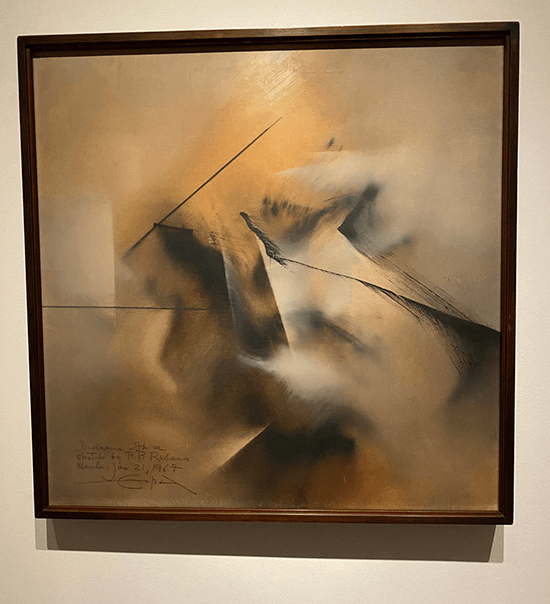

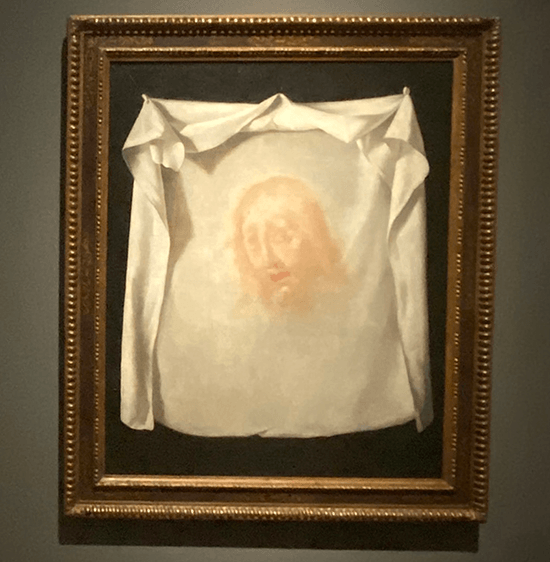

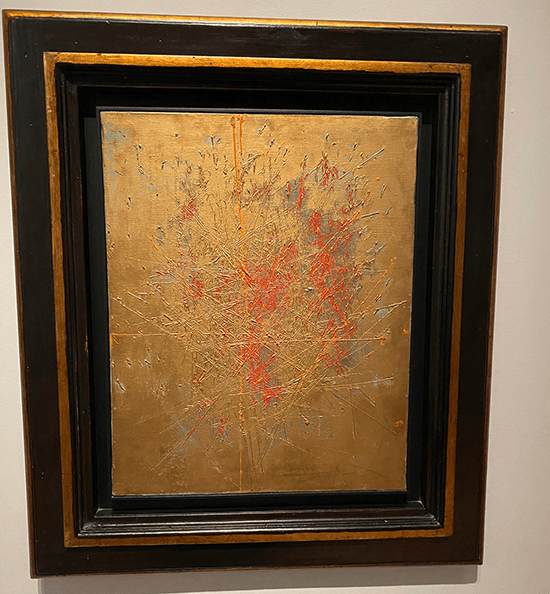

On one of the walls hangs a painting, circa 1660, by Spanish master Francisco de Zurbaran, called “The Holy Face.” It depicts the Shroud of Turin, with its imprint of Christ’s face. Alongside are two of Zobel’s works. In the earlier one, called “The Holy Face II,” made from oil and bronze glitter on canvas in 1959, one sees what Zobel absorbs from the original: black shadows, cuts and lashings on the canvas, some of them red, seemingly bloodied, all against a shiny golden background.

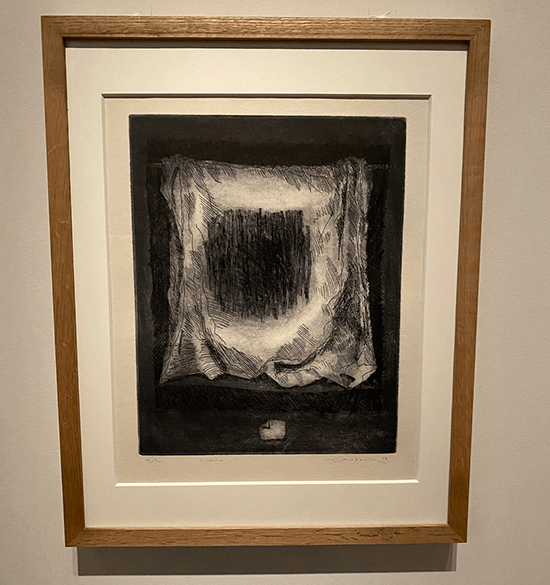

The second work, “The Holy Face (Veronica)” is an etching from 1964, where the shroud is recognizable, but the face of Christ blotted out by thick black strokes. Above all three works, a quote from his Sketchbook No. 5: “Drawing from paintings is a way of seeing them. It cleans the eyes and leaves the most unexpected things in the subconscious…”

As part of his research, co-curator Felipe Pedera visited Manila in 2019, where he first touched base with the Ayala Foundation. “I went to Manila in 2019 as I thought Zobel’s Filipino background was fundamental to present at the show. Previous exhibitions on him had not given much attention to this but, in our opinion, it is only when considering Manila as the point of origin that his cosmopolitan artistic personality begins to make sense. My visit to Manila completely changed the way that I saw his work. The exhibition tries to reflect how the Philippines was not something he left behind when he moved to Europe, but instead a place that had completely shaped the way he looked at the world and the way he created as an artist.”

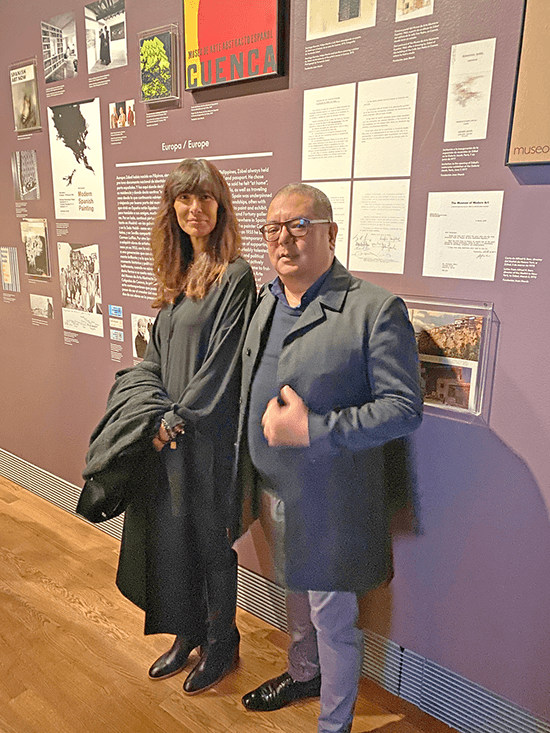

Mariles Gustilo, senior director, Arts and Culture of Ayala Foundation, mentions that 27 pieces from the Philippines made it to the exhibition, loaned from Ayala Corporation, the Ayala Museum, the Ateneo Art Gallery, the Lopez Museum and Library, and private collections.

To give Filipino art lovers something to look forward to, Pereda discloses that in 2024, to mark the 40th death anniversary of Fernando Zobel, the exhibition will travel to Manila.

In today’s parlance, we would label Zobel a disruptor, a game-changer. He did this both as an artist and as a patron and supporter of the arts. A section of the exhibition also brings to light this side of his work, underscoring his pioneering spirit as the founder of two institutions that now play vital roles in the art history of two countries, the Philippines and Spain.

In 1961, he left the bulk of his Filipino art collection to the Ateneo De Manila University, where he taught art history in the 1950s. Today, the Ateneo Art Gallery is arguably the most important repository of Philippine modern art. His typewritten syllabus for his “Introduction to Contemporary Painting” course hangs for viewers to peruse. In the introduction, he states: “This is going to be an informal course. Discussions will be encouraged by every means at my disposal. Do not hesitate to interrupt, ask questions, dispute points, or get involved in arguments. I do not have all the answers. In fact, I intend to learn a good deal from this course myself.”

Opposite this, visitors get a glimpse of a montage of photos and mementos of The Museo Del Arte Abstracto in Cuenca in Spain, which Zobel founded in 1966. He did this to signal support for Spanish artists working in abstraction, who, at that time, did not all enjoy commercial success. A notable visitor to the museum, Alfred H. Barr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, called it the most beautiful museum he had ever seen. Iñigo Zobel remembers spending summers in the museum, selling tickets.

The exhibition at the Prado recognizes Fernando Zobel’s pivotal roles as artist and advocate. Co-curator Manuel Fontán del Junco believes that the time is ripe for this honor.

“The Greeks had a word, kairos, to refer to an important moment in time. In the case of Zobel, indeed, the kairos is today. Why? Let’s say that a series of circumstances have arisen that in some way have had as their main consequence this unusual exhibition: Zobel, an abstract artist from the second half of the 20th century, in one of the great museums of the world, a museum that has just turned 200 years old, and conserves and exhibits art from Greece and Rome to the 19th century.”

At the last room of the exhibition, the curators leave viewers with this: “This exhibition is dedicated to all those who at some point, perhaps as young students, were thrilled and entranced by the genius of a drawing, by the haunting beauty of a figure or a brushstroke, and dreamt — just for a moment — of devoting their lives to art.”

A dedication that could have come from Fernando Zobel himself.