The enduring legacy of Talisay’s Balay ni Tana Dicang

I am a sucker for old houses, or “heritage homes,” a term for historical residences that remain standing today, yet continue to be rooted in their past glories somewhere in the mists of time. These homes paint a picture of their era, and of the people who inhabited them. Wandering around an old house is the best way to understand how people lived, what they thought, their values and aspirations, and how time eventually treated them. They are a time capsule of history — social, economic, and political.

A recent tour of heritage homes in Negros Occidental brought me once again, after 12 years, to Talisay City, to visit one of the most sympathetically and authentically restored examples of a heritage home.

The Balay ni Tana Dicang was a grand home built in 1872, with later additions in the late 1880s. Tana Dicang was the nickname of Enrica Alunan Lizares, “Tana” being short for Kapitana, referring to her status as a leader of the community.

Tana Dicang was married to one Efigenio Lizares, and bore him 16 children. The present-day representative of the family foundation that maintains the house museum, Adrian “Adjie” Lizares, states matter-of-factly that “not much is known” about Tana Dicang’s husband, except that he died shortly after she bore their 16th child.

This fact somehow underscores the matriarchal dominance of Tana Dicang over the house named after her. She ran the family’s haciendas and kept copious ledger notes of the businesses, some of which survive to the present day. A keen matchmaker, Tana Dicang married off her children efficiently, generously providing hacienda properties to enable financial independence for the couples. A strict code of industriousness in the home was valued, and for a time, the women of the house were preoccupied with making fashionable ternos.

Built in the grand tradition of a typical Philippine bahay na bato, the wooden upper part of the house is set on a weathered yet elegantly articulated stone base with substantial door and window frames, gently arched on top; pilasters defined by cornices on top and below; and relief medallions. The upper, wooden section of the house is replete with typical sliding capiz shell windows and decorated with finely carved balustrades, as well as wooden medallions echoing the stone versions below.

Balay ni Tana Dicang is one of the first successful house museums in Negros Occidental. Its development was aided by a family foundation formed to carry out Tana Dicang’s specifications in her will that the house was to be preserved and maintained as part of her legacy to the family, along with the family cemetery and the carroza used for fiesta processions.

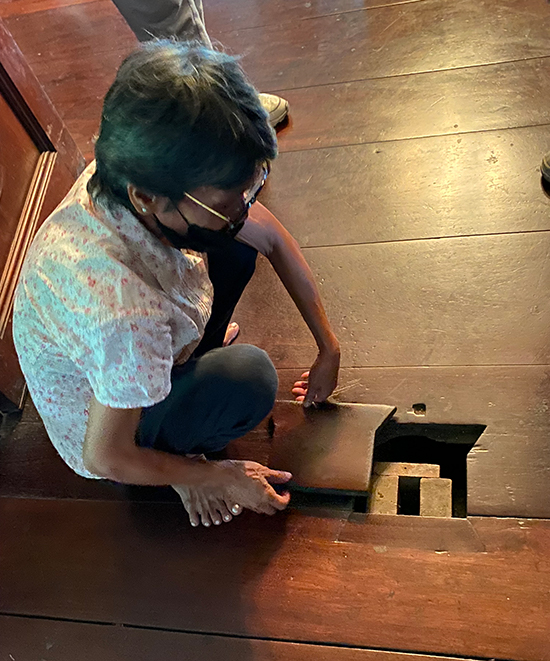

The entrance to the home is through large wooden double doors on the ground floor, an area more commonly known as the silong. This huge space encompassing the footprint of the house usually served as the venue for the family’s business dealings, household operations, and storage of goods. Animals, and later, cars, were kept in this area. One espies a silver carroza, used for fiesta processions, tucked between the columns. The series of rooms along one edge were once used as offices or storerooms. These days, the silong has been paved over with colorful machuca (cement tile) flooring. Adjie has converted a whitewashed room off the side into a contemporary art exhibition space that sponsors yearly artist residencies. This room used to be the despacho, from which Tana Dicang’s sugar produce was dispatched to Iloilo on sea vessels known as lorchas. The lorchas returned to Talisay with Iloilo-purchased goods that were sold from the silong by the ever-enterprising Tana Dicang.

Access to the upstairs is via a grand wooden staircase that begins its ascent from this floor. The staircase is a tour-de-force of woodcarving: the handrail and bottom rail encase an ornate screen in a neo-Gothic vine design. The pattern is carried upstairs, in the upper reaches of the staircase, and the large, pierced wooden medallions are inset into the interior walls, enabling the flow of air from room to room. Tana Dicang is said to have hired woodcarvers from Batangas, likely Chinese artisans, who had previously worked on the grand house of the revolutionary hero Aniceto Lacson in nearby Manapla.

As an important pillar of her community, Tana Dicang hosted many important personages of her day, including Philippine presidents Quezon and Osmeña. The upstairs public rooms are spacious and elegant, and well suited to entertaining large groups of visitors. In the reception area, light streams in with a lace-like effect through diagonally set capiz-shell inserts on sliding windows and the upper ventanillas. The extensive matching furniture set in the reception room is composed of original pieces likely from the famed Ah Tay workshop in Manila.

Multiple doors lead off from the sala to several bedrooms along the sides of the house. Tall Venetian mirrors, a bronze bust of Tana Dicang, and family photographs through generations add to the air of an elegant home.

Across the reception area, on the other side of the grand staircase are two large rooms devoted to dining: one for the grand dining table, and another for the generous buffet table. The buffet table was laid with fresh banana leaves, vintage crockery, and silverware from the many platadors filled with porcelain, glass, and silver that lined both dining rooms. Adjie graciously provided a sampling of Talisay specialties, including a special bicho-bicho with a crunchy sugar shell, a dark muscovado bibingka, and pancit lomi, served hot from a beautiful white heirloom tureen.

Balay ni Tana Dicang is one of the first successful house museums in Negros Occidental. Its development was aided by a family foundation formed to carry out Tana Dicang’s specifications in her will that the house was to be preserved and maintained as part of her legacy to the family, along with the family cemetery and the carroza used for fiesta processions. It is fortunate that every effort was made to preserve its authenticity while remaining true to its original state. The pale, watery blues, greens, and whites of the original painted walls were discovered after layers of paint were painstakingly scraped off to reveal the casein, or milk-based paint coloring, a long-lasting finish favored over centuries. An overall light approach to preservation is evident in the gently faded air the passage of many decades has bestowed upon the house.

Plans for the house are ever evolving. As we stood on the stone azotea overlooking the lush gardens, presided over by a beautiful, hundred-year-old Talisay tree, Adjie remarked on possible future plans to clear some garden space, enabling events that could breathe new life into the house and bring in additional income to help preserve this legacy of a remarkable woman who left her mark in this corner of Negros Occidental with the gift of her beautiful home.