The sacred as a child

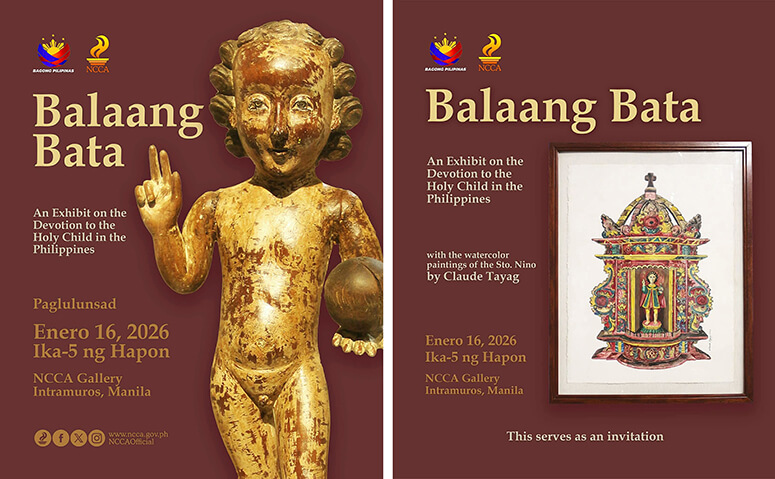

At the National Commission on Culture and the Arts Gallery, a small figure stands at the center of the room. The ongoing exhibition “Balaang Bata – An Exhibit on the Devotion to the Holy Child in the Philippines” gathers centuries under one roof and lets them face the present.

Side by side in the exhibition are centuries-old sculptural images of the Santo Niño on loan from private collections and watercolor renditions by Claude Tayag, whose decades-long study of the image shapes the show’s contemporary lens. The pairing lets viewers encounter the venerated image through both the original devotional object and a present-day artist’s hand.

The show opened on Jan. 16 under the leadership of Eric B. Zerrudo, who began his term at the NCCA with this invocation of the Holy Child. “I wanted to start my term on the right foot,” he said at the exhibit opening. “With the challenges and speed of the previous year and my compounded role as chair and executive director of the NCCA, what better way to start the new year than with blessings from the ‘Balaang Bata?’” This sentiment has shaped the physical space of the gallery. The rooms do not feel like a dry textbook. Instead, they are layered with faces, gestures, and gold crowns. Visitors encounter the child as king, pilgrim, or guardian.

The Santo Niño arrived on Philippine shores in 1521 as a small wooden image offered during the first encounter between Spain and the islands. Filipino hands transformed this gift of conquest into something approachable and tender. Families dressed the figure according to their means and imagination. They used velvet and gold or pinned small medals and ribbons to the fabric. Some placed the image beside photographs of relatives and school report cards.

In many homes, the Santo Niño sits near the dining table where daily life unfolds. Faith here shares space with hunger, bills, and celebration. This devotion rides jeepneys as decals and mini statues. Each January, it spills into the streets, where drums and dancing feet carry prayer through the city.

The curator, Francis Ong, brings the perspective of a collector who sees objects as storytellers. “We collect to be able to share it back to the community,” he said. “We’re helping build the narrative, the story, because this is the history of our people.” The exhibition includes loans from his collection and from fellow custodians such as Jayson Maceo, Jun Fulgencio, Anthony Agustin, Oliver Abusan and Claude Tayag. These pieces show regional styles and workshop signatures. You see figures with sweet expressions and rounded cheeks standing near those with a solemn gaze. The varied carving styles and fabrics provide a visual record of provincial history. The viewer is left to find the links between these different regions and eras.

Claude’s own collection grew from a painter’s eye before it became part of his work in food and writing. His early years trace back to Baguio landscapes and the guidance of his mentor, Abé Cruz. In the late 1970s, a young Claude prepared for a one-man show arranged by Larry J. Cruz. He traveled to Iloilo City to visit his aunt, Dr. Alicia Tayag Saldaña. It was the height of the rainy season, and he was often stuck indoors while the household was at work or school. To keep his painting fingers nimble, he painted still-life watercolors of the hundreds of folk santos staring down from her shelves. His aunt taught him to look beyond surface charm and to notice the carving and regional character of each piece. This immersion led him to become an avid collector himself.

Cruz later opened Café Adriatico in Malate, where several of Claude’s santo paintings hung on the walls. Diners sat among these images while sharing cakes and coffee. One dessert, a pandan-flavored gelatin in a pool of cream and condensed milk named Claude’s Dream, became a signature that tied his name to the menu.

Years later, Cruz invited him to cook publicly at Ang Hang Restaurant in Makati City. Claude translated festival imagery into dishes and recognized cooking as another creative field. His weekly column for this paper, “Turo-Turo,” followed, then books on Filipino gastronomy. Through all of it, painting remained his steadying force.

In 2019, Claude marked four decades as a watercolorist with a retrospective at the National Museum of the Philippines. He donated five large Santo Niño paintings to the collection, which now hang on the second level of the National Museum in Cebu. They are the first works a visitor sees upon exiting the elevator. During this time, he and Floy Quintos began planning a book titled Doble Bendita to pair the watercolors with the antique santos that inspired them. Quintos died of a sudden heart attack in 2024, an event that stalled the project until Dr. Chita B. Gatbonton took over. She is now continuing the work Quintos began.

Many of the watercolors now on view were painted during the pandemic, when time at home forced an inventory of the studio. Zerrudo visited Claude in Angeles City shortly before the show and found a group of 35 Santo Niño paintings ready for the public. These works treat the sculptures as a starting point. The watercolor medium provides translucence and soft edges that wood cannot achieve. Layered washes create the look of luminous fabric and delicate lace. Claude gives the child a knowing look. The face lands somewhere between a holy icon and a familiar companion. Viewers who grew up with these figures at home will recognize the specific weight and presence of the images.

The exhibition follows the figure’s journey from a colonial encounter into the daily fabric of Filipino life. Artists and collectors continue to return to the same image to find fresh angles in carved wood or a wash of watercolor. Belief moves from the private household into the public institution. The Santo Niño stands as memory, petition, and gratitude. It remains a subject for art that is as intimate today as it was centuries ago.

“Balaang Bata” runs until Feb. 24 at the NCCA Gallery on Gen. Luna Street. The setting in Intramuros adds singular gravity to the show because these walled streets witnessed the arrival and transformation of the figures on display. The exhibit is worth the time and focus. In a season of quick openings and social media snapshots, these sculptures and paintings offer something more durable. They are a return to the faces and velvet garments that have accompanied Filipino lives for centuries.