How Marcela Agoncillo sewed her way into history as the ‘Mother of Philippine Flag’

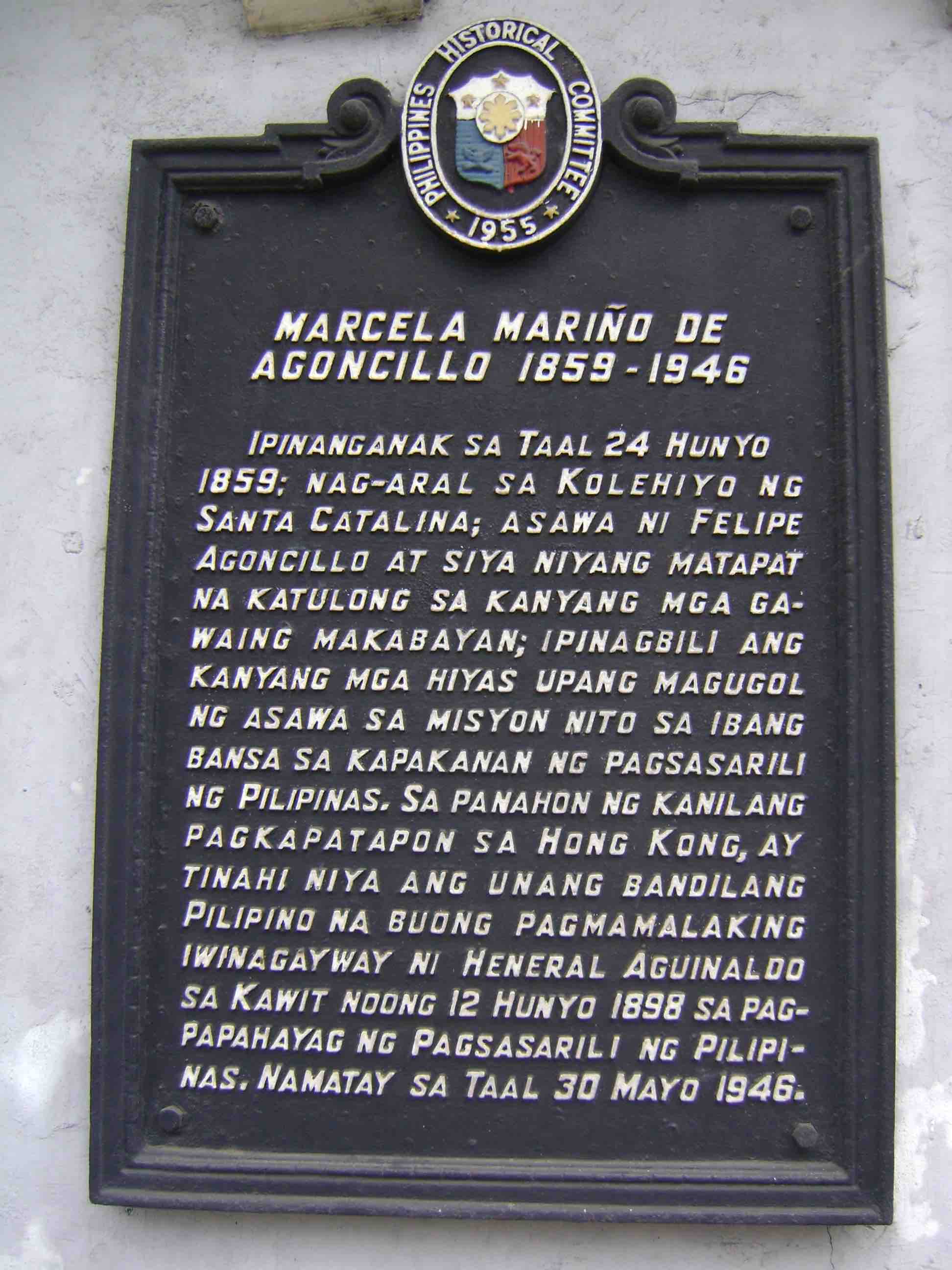

Born on June 24, 1859 to an affluent family in a town known for embroidery—Taal, Batangas—Marcela Coronel Mariño was perhaps expected to learn sewing like other young women of her generation.

But no one could have anticipated that sewing would propel her to national prominence. And yet, that’s exactly what happened. Seventy-five years after her passing on May 30, 1946, this woman’s contribution to national history continues to be celebrated.

Marcela Agoncillo—who at the time of her singular act was already married to revolutionary stalwart Felipe Agoncillo—is recognized as “The Mother of the Philippine Flag” for being the principal seamstress in making the first banner representing the Philippine republic. It would serve as the inspiration for the flag that we know of and use today.

The flag was officially presented to the public on June 12, 1898, at the Aguinaldo Mansion in Kawit, Cavite, upon the Declaration of Independence led by Emilio Aguinaldo who would become the first Philippine President.

From historical accounts, it was Felipe Agoncillo’s friendship with Aguinaldo that led to Marcela being designated as flag maker.

With the nation observing National Flag Day on May 28, a celebration that continues officially until June 12, we’ve gleaned the following information about Marcela Agoncillo and the Philippine flag from published sources and previous visits to sites related to her life.

Although born in the embroidery town of Taal, it was said to be at the Beaterio de Santa Catalina, a convent school for girls in Intramuros, that Marcela learned sewing, needlework and similar “feminine crafts,” apart from Spanish, music and social graces, under the tutelage of Dominican nuns. There are reports that she grew up to be a noted singer who would occasionally appear in zarzuelas in her native Batangas.

Marcela got married at age 30 to a neighbor, Felipe Agoncillo, who like her belonged to a wealthy clan. He was a lawyer who would become a prominent figure in the clamor for Philippine Independence and eventually as the country’s acknowledged “First Diplomat.” When he was being targeted by Spanish authorities as a filibuster, he went into self-exile in Hong Kong in 1896, with Marcela and their daughters soon joining him.

It was in their residence in Morrison Hill in Wan Chai where personalities clamoring for Independence would meet including Generals Emilio Aguinaldo and Antonio Luna, leading to the founding of the so-called Hong Kong Junta. Learning of her talent in needlework, Aguinaldo requested Marcela in 1898 to sew the Philippine flag based on his design.

She is said to have enlisted the help of her seven-year-old daughter Lorenza and a friend, Delfina Herbosa de Natividad, the niece of Jose Rizal (daughter of his sister Lucia), for this important work. The three supposedly worked manually and with a sewing machine, and were said to have started over when the rays of the sun turned out askew. The flag used silk bought from a shop in Hong Kong and was embroidered in gold and contained stripes of blue and red and a white triangle with the sun and three stars on it.

It took her five days to make that National Flag, and when completed, she delivered it to Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo.

Information from the Department of Foreign Affairs delves into the symbolisms contained in the Philippine flag. “The concept was to reflect the ideas and aspirations of the Filipino people. The equilateral triangle, many believed, was a memento of the Katipunan standard. The 3Ks of the Katipunan, Kataas-taasan, Kagalang-galangan, Katipunan ng Bayan, were sometimes arranged in triangular manner, considering also that most of the insignias of the Katipunan were patterned after Masonic emblems—triangular in shape.

“In the center of the white equilateral triangle is the golden sun, with eight rays and three five-pointed stars in each corner. The eight rays represented the first eight provinces that courageously defied and revolted against the Spaniards – Manila, Cavite, Bulacan, Pampanga, Tarlac, Batangas, Laguna and Nueva Ecija. Similar revolts spread to other parts of Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao – the three geographical areas, represented by the three five-pointed stars.

“Color white, symbolizes purity and peace; the blue symbolizes the high political purpose and ideals; while courage, bravery, heroism and willingness to shed blood in defense of the Country of the Filipino patriots are embodied in the red field.”

While it was on June 12, 1898 that the flag was raised and initially shown to the public, its first unfurling actually happened a few days earlier on May 28. The National Historical Commission says that it was done at the Teatro Caviteño in Cavite Nuevo (now Cavite City) after the Philippine Revolutionary forces defeated the Spanish forces in the Battle at Alapan, Imus.

The NHC has also clarified: “Contrary to popular belief, on 12 June 1898 the Philippine flag was waved by Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista, not by Emilio Aguinaldo. It was done at the window of Aguinaldo’s bahay na bato, not at the balcony which did not exist at the time.”

It was President Diosdado Macapagal, through Proclamation No. 28 in 1962, who declared June 12 as Philippine Independence Day. Presidential Proclamation No. 374 meanwhile was issued on March 6, 1965, declaring May 28 as National Flag Day to commemorate that victory. On May 24, 1994, President Fidel Ramos issued Executive Order No. 179 to allow government offices and residences to display the Philippine national flag from May 24 to June 12 of every year.

There is just something dramatic and stirring about the story of three females toiling in crafting the flag representing a nation’s ideals that the image has been depicted in various ways. It has been seen on calendars and Philippine currency and in a range of artworks. Perhaps the most popular is National Artist Fernando Amorsolo’s painting, The Making of the Philippine Flag, where he casts the trio in traditional Philippine clothes as they go about their important task.

Another National Artist, sculptor Napoleon Abueva, portrayed the historical event in sculptural form which is reported to have been patterned after Amorsolo’s work. It has been referred to alternately as Three Women Weaving the Philippine Flag and Three Women Sewing the Philippine Flag. Made of concrete and polychrome where portions of a sculpture are given color (in this case, the Philippine flag), the assemblage is mounted on a pedestal and was installed in the UP Diliman campus in 1996. It is found at the edge of the UP Ampitheater, near the UP Lagoon.

When Marcela passed away in Taal in 1946 at age 86, her remains were brought to La Loma Cemetery in Manila to be interred alongside those of her husband Felipe who had died in 1941. It is not known when and why the couple’s remains were later transferred to the cemetery beside the Santuario de Santo Cristo Parish Church in San Juan City. A historical marker indicates the couple’s burial site.

In Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Antiquities Authority installed a historical marker in what is now the Morrison Hill Playground in Wan Chai to memorialize the area where the first Philippine flag was sewn. The exact location of the Agoncillo house which had served as a sanctuary for revolutionary exiles is no longer known.