Understanding my Chinoy identity through the past

Growing up mixed heritage adds a lot of spice and richness into life, especially culture-wise, but it also has its own struggles. Society finds it easier to understand things as binaries or dichotomies, so when it comes to being both Chinese and Filipino, it’s hard to digest the concept of embracing both.

Apart from the internal struggle, it doesn’t help that I encounter a lot of racial stereotypes when I interact with others.

There are two typical conversations that I frequently get in my life. When a Filipino asks me where I live and I answer "Manila," an immediate reply would be "In Binondo?" From then on, I would preemptively answer: "Manila, but not in Binondo."

Another is when Chinese Filipino acquaintances’ first small talk would be: "Who are your parents? What’s your business?"

Well, there’s no right and wrong with how people want to interact and connect, but I think that there’s so much more to ask about me other than a background check for a first conversation.

Having spent my whole professional life in media and grown up in more multicultural environments compared to my peers, I get worked up when it comes to stereotypes of my race—Binondo, family business, and marrying another Chinese.

My family does a very good job of exposing me to global ideas, yet we appreciate our Chinese heritage and respect other cultures, especially local Filipino culture. But I also know that I have friends who come from a strong traditional Chinese upbringing and they experience many tensions with tradition.

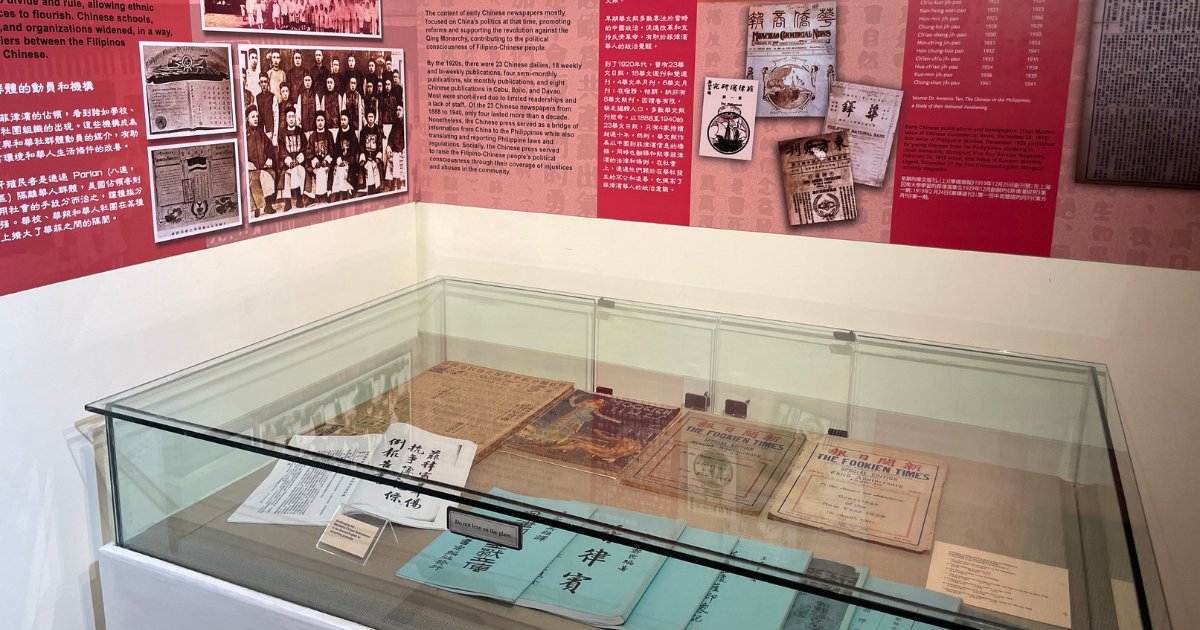

Bahay Tsinoy, museum of Chinese in Philippine life

Bahay Tsinoy, which reopened last month, has helped me become more empathetic about where these stereotypes come from and how history bleeds into the experience of Chinese Filipinos or “Chinoys” of today.

“From the museum, we are showing them that in every aspect of Philippine life–history to food to languages–you can see Chinese influence,” Ang Chak Chi, the Managing Director of Kaisa Heritage Foundation–an organization that aims to preserve Chinese culture and heritage in the Philippines—told PhilSTAR L!fe.

The museum was built to educate Filipinos, with or without Chinese heritage, about the history of Chinese Filipinos through research and documentation, as well as their past experiences and contributions to Philippine society.

It also aims to combat the common misconception that “Chinese Filipinos are foreigners.”

“Although we look different from the rest of the people in the Philippines, Chinese Filipinos were born here, raised here, and most likely will die here,” said Ang.

“In the museum, you’ll see that the Chinese Filipinos were in many parts of history in the Philippines, from the Spanish time, American time, and Japanese time.”

A generational cycle

It's written in history that the Chinese have been in the Philippines for a very long time, but the museum dives deeper into their experiences and how Chinese Filipinos of today can relate to the past generations.

During the Spanish period, the Chinese came to the Philippines as traders and were called “Sangleys,” derived from the Hokkien word “Siong Lai,” which means frequent visitors.

Even though the Sangleys were ranked very low and were restricted to walled cities called “Parian,” Chak shared that the Chinese were already very “purist” by nature. They looked down on intermarriages even with Filipinos of higher class.

“The Chinese live in their own world in Binondo, so the interaction with the outside world and with Filipinos is close to nothing,” said Ang.

It’s no wonder why there are still Chinese, though they have lived in the Philippines for a very long time, who are strongly against intermarriages with other races because of an inherent desire to “keep the blood pure.”

There is less resistance in the modern day, but matchmaking between Chinese called “kai shiao,” which means “to introduce,” continues to be a big deal with Chinese families.

History also records of Chinese venturing out and interacting with Filipinos in the country. Unions, then, were inevitable and their children were known to be Chinese Mestizos. They identify as Filipinos with Chinese descent.

Even the Philippines’ national hero Jose Rizal is a fifth-generation Chinese, who eventually belonged to the higher Illustrado class. Other pivotal characters in the Philippine revolution such as Emilio Aguinaldo, Andres Bonifacio, Antonio Luna, and Marcelo Del Pilar were also of Chinese descent.

Though this seems like a small detail to others, it paints a picture that it takes generations of Chinese living in the Philippines to identify as Filipino.

There were droves of Chinese immigrants who arrived before and after the Second World War, and are the ancestors of Chinese Filipinos of today. These Chinese were historically limited to trade, business, and finance because of their inability to secure licenses and citizenship in the Philippines until the naturalization law was passed.

Now, Chinese Filipinos have branched out across industries and many have waved the Philippine flag with their success.

Notable names include Ramon Ang and Lucio Tan in business, Rachelle Ann Go and Jose Mari Chan in entertainment, President Bongbong Marcos and the late Cory Aquino in government, and Samboy Lim, Gretchen Ho, Agatha Wong and Chris Tiu in sports.

According to Chak, the phenomenon of Chinese immigrants settling in the Philippines and making it their home is not over and is bound to continue repeating itself; hence, emphasizing the importance of sharing the Chinese Filipino history.

“At first we thought the work in integration would be done after the museum but we noticed lately that there are many Chinese immigrants again. You cannot really say if they are here to stay or not, but those who will stay will go through the process,” said Ang.

Best of both worlds

Bahay Tsinoy also shows the distinction between “Chinoy” culture and Chinese culture—and how special it has become.

“Definitely as Chinoy, you enjoy the best of two worlds. Chinese culture and tradition are not perfect, so as Filipino culture. As a Chinoy, you are in a better position to pick up the good things from Filipino and Chinese culture and merge them into Chinoy culture,” said Ang.

In food, you will not be able to find lumpiang shanghai, lumpiang ubod, and pancit canton anywhere else in the world but in the Philippines.

In language, Chinoys are known to combine Tagalog, English, and Chinese words together in one sentence.

In understanding roots, Chinese Filipinos are able to celebrate their heritage, yet they don’t have to fear making choices outside of culture and tradition.

Bahay Tsinoy is located at 32 Anda St., Intramuros, Manila. It's open from Tuesdays to Sundays, from 1:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m.