Bahay tsinoy: Our intertwined past, present and future

Last June 24, during the Dia de Manila celebrations, I visited the little-known but beautiful little pocket of history in Intramuros known as Revellin de Recoletos.

This was during Spanish times a fortress to defend the walled city against uprisings or revolts specifically emanating from the Parian, or the Chinese ghetto where the community of the Sangleys (“frequent visitors”) and Filipino-Chinese mestizos lived. It’s important to note that as you read this story.

This fortress has since been converted into a trade school, the Escuela Taller, where wood carving and other skills connected with heritage restoration are taught. But that’s a story for another time!

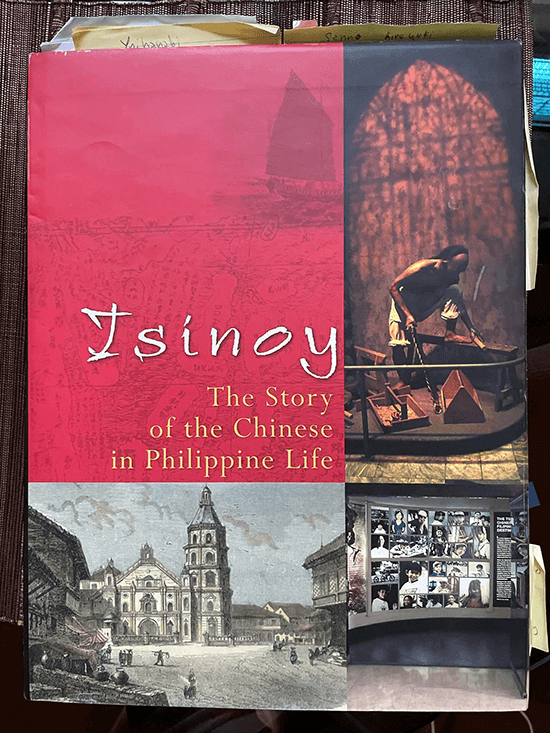

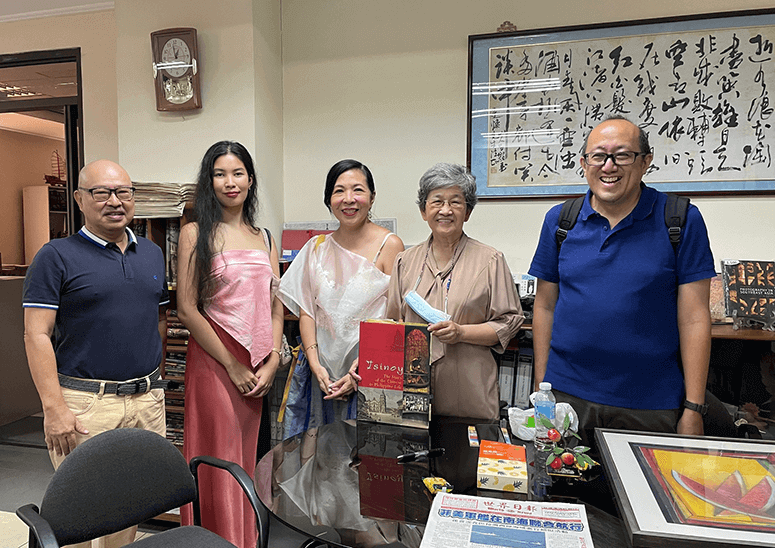

I had been invited to give a talk about my children’s books and in the audience was well-known Tsinoy advocate Teresita Ang-See, whom I met afterwards. I received a copy of Tsinoy, her beautiful, hardbound book, which, aside from providing a rich history lesson, details what you will see during a visit to Bahay Tsinoy.

Bahay Tsinoy is a museum in Intramuros of everything Chinese and Filipino intertwined. It closed for two years during the pandemic for renovation, so when I saw photos of the recently reopened Bahay Tsinoy, I knew I just had to visit. My friend Anson Yu, who had invited me to join the Dia de Manila talks, happily offered to tour us around.

I read Ang-See’s Tsinoy book in order to better appreciate the museum and did not realize that the book, beautifully researched, written and presented, was itself a fascinating journey back in time to ancient China, from which emanated the culture, trade and eventually the bloodlines of present-day Tsinoys. It deserves not only to sit prettily on your coffee table but to be savored slowly, page by page, with a cup of jasmine tea.

The threat of rain did not stop us from meeting up with Anson promptly at 10 a.m. on a Tuesday. We were able to park at the basement of the museum building and, being in need of coffee, walked to Papakape in Fort Santiago before tackling the tour.

Any walk through Intramuros takes you quickly back in time, as you pass colonial architecture and interesting-looking cafés, notably the Belfry Cafe right beside the Cathedral, which is itself beautifully lit inside in the morning.

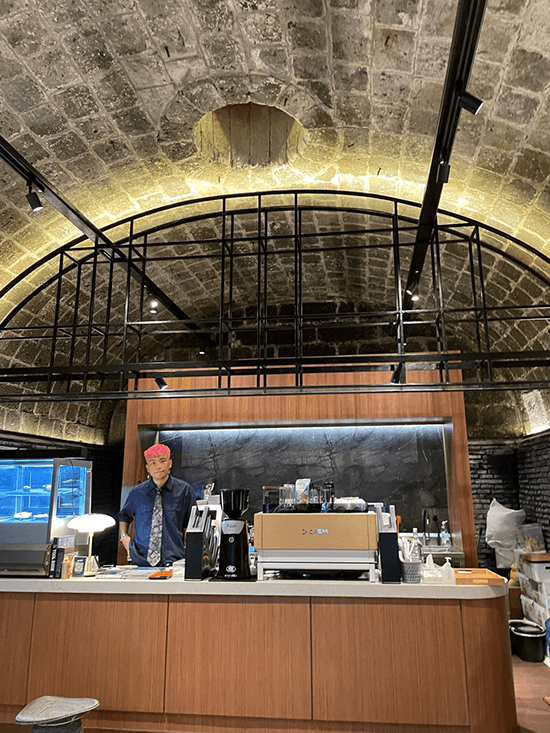

We walked past a cobalt-blue tranvia complete with costumed drivers and through the gardens of Fort Santiago, which never fail to bring waves of imagined memories. Tucked in a quiet corner within the fort itself is Papakape, a cafe with real Pinoy style and attitude.

We were fortified with delicious coffee drinks and kakanin given a unique Pinoy twist such as sago and gulaman coffee, suman filled with red beans, a pretzel stuffed with kesong puti and a donut topped with coconut jam. Everything was so yummy we are now wishing for a Papakape in our Laging Handa neighborhood!

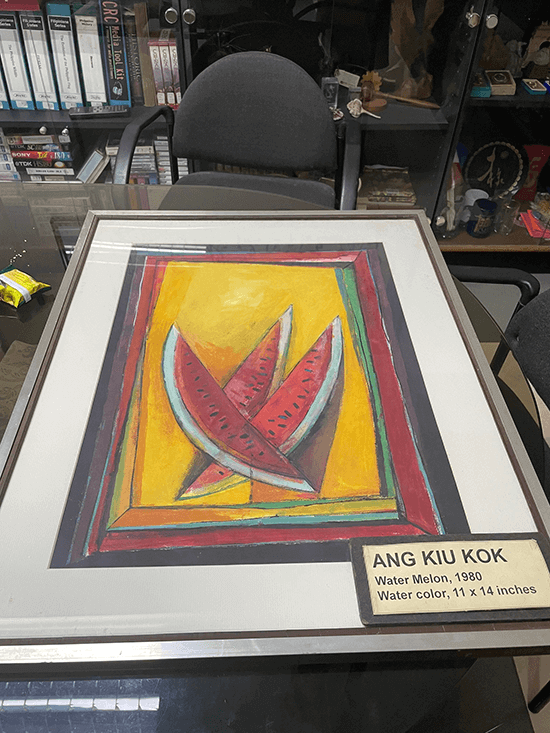

Back at Bahay Tsinoy, which is housed in a heritage-style building for Kaisa Para sa Kaunlaran Inc, the museum occupies only two floors at present. There are still plans afoot to expand and improve the gift shop, and find a way to showcase a treasure trove of old Chinese newspapers discovered in a toyo factory. Many opportunities for information lie within those carefully kept periodicals and one day they may help Tsinoy families trace their family trees!

But that is getting ahead of the story.

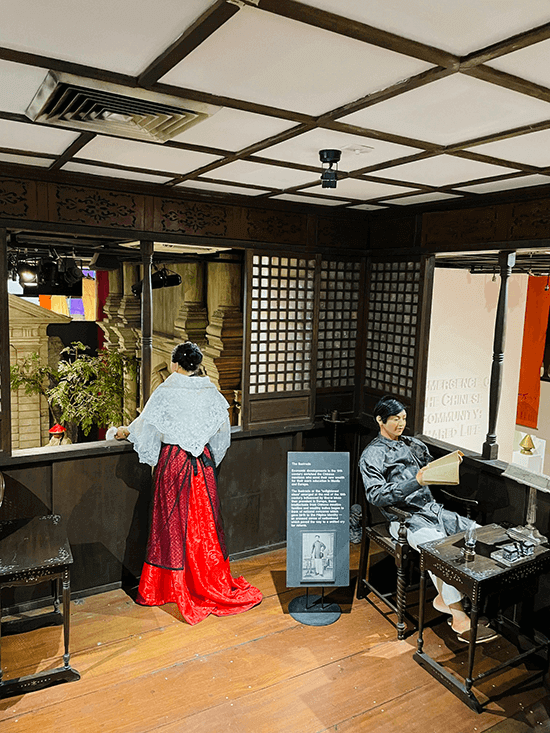

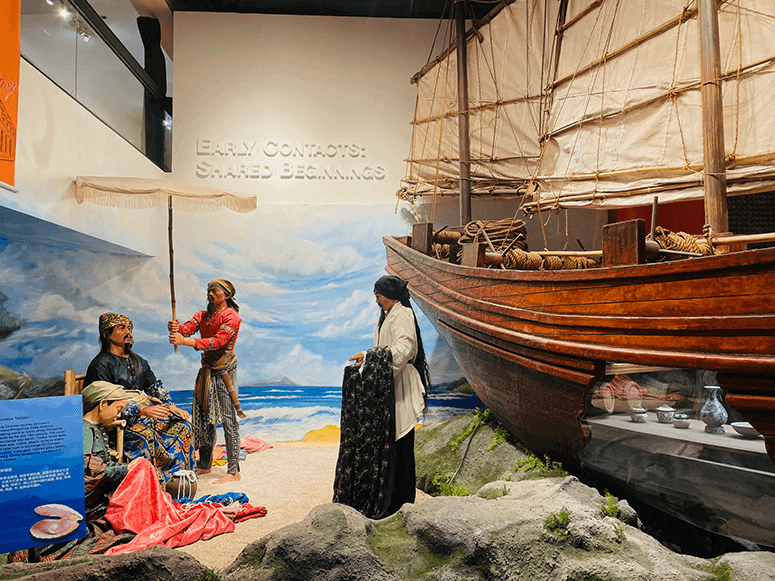

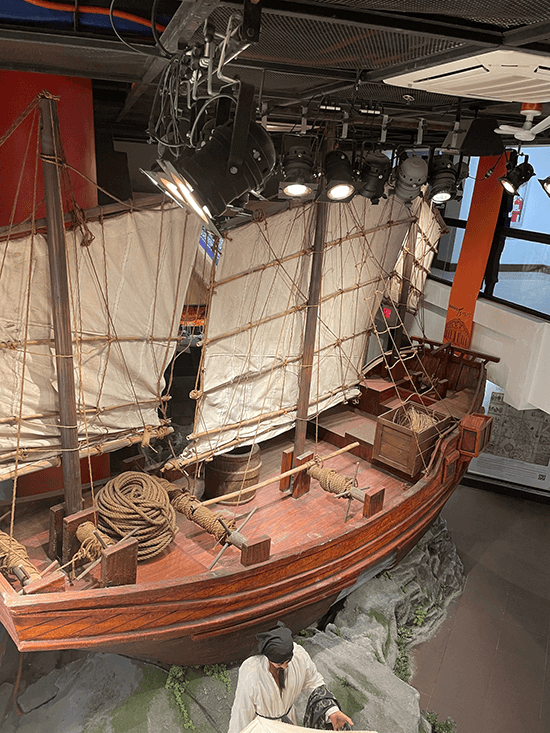

Since I had read Tessie’s book, I felt more prepared to appreciate the museum offerings. But I did not anticipate the drama and visual impact of its carefully designed, life-size dioramas, including a not-too-small Chinese junk, a sound-light depiction of Binondo in colonial times, original documents, gorgeous porcelain and more. Balconies overlook the ground floor so you get a feel for what was on the streets and hidden away (or not so hidden away) in the bahay na batos.

Adding to our appreciation were the inputs of Anson Yu, who conducts tours of Intramuros with Ivan Mandy and my DLSU batchmate Ang Chak Chi, who is a director of the museum. They shared a lot of fascinating things that weren’t in the book, some of it off the record!

When you enter the first floor of the museum, a tableaux of Chinese traders complete with boat greets you after you have perused the introductory panels. But this boats boasts a hollow belly with real pottery inside!

Coming to the depiction of the gate of the Parian, I felt a connection because on my last trip to Cebu to promote my rabbit books at Big Bad Wolf, we visited the house-turned-museum Casa Gorordo. There, I saw my Veloso family listed as among those living in the Parian of Cebu! I asked my cousin Jojo Veloso to send me our family tree and there they were, my Chinese mestizo ancestors!

And whether in Manila or Cebu, the Chinese were often mistreated, leading to uprisings (hence the Revellin de Recoletos original purpose). We do indeed have many shared miseries, whether during Spanish times or the Japanese Occupation.

I always thought the rice terraces were our particular invention but no, they are actually proof of early cultural exchanges as we, together with other rice-growing places in Asia, use the same kinds of rice, the same palayok type cooking vessels in addition to those iconic terraces.

And while it was first thought that trading between China and the Philippines began only during the Song dynasty, the discovery of perfect specimens in gravesites showed that Chinese pottery from the earlier Tang dynasty had already reached our shores, likely from Arab traders.

The Chinese traders who bartered and later married and settled down in our islands saw to the betterment of their communities because if those thrived, so would they. The Tsinoys supported and participated in the uprisings against the Spanish, Americans and Japanese. The Philippines had become their home.

In what aspect of Philippine life is their impact not felt today, whether it be food or language, architecture (like in Vigan), business, religion, politics, fashion, education, philanthropy? Are not many of them the taipans contributing to our economy? Even Jose Rizal and seemingly most of our heroes were of Chinese descent.

Bahay Tsinoy is a feast of friendship, family ties, a shared history of triumphs and hardships. There are just too many heartwarming to be told, too many horrendous tales to sigh over. You will be fascinated, saddened, encouraged, inspired.

There are more that bind rather than divide all of humanity as we see overlapping layers of culture, whether it be the fashion interchange between China’s Madame Song and France’s Pierre Cardin or the many generations of Chinese and Filipinos that have mutually contributed to each other in our lands.

The work is far from over for Tessie Ang-See and her indefatigable team. She laments the high cost of obtaining original prints to document the Tsinoy story and other expenses.

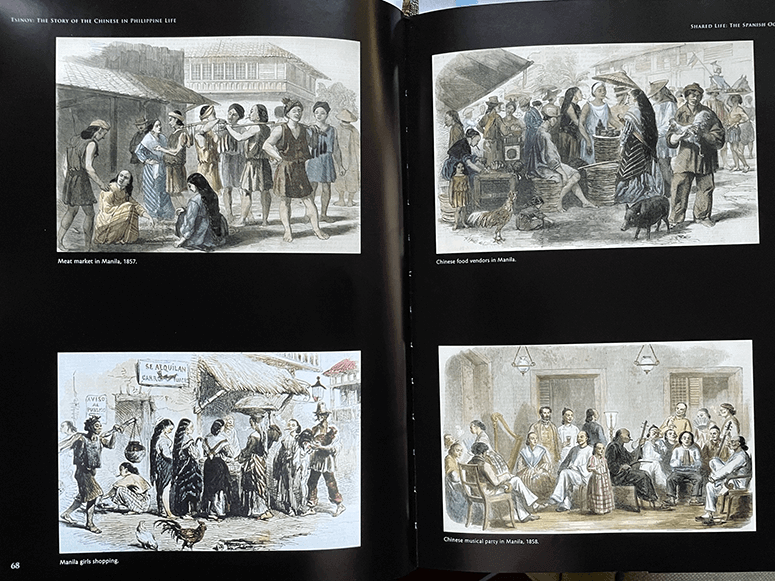

“Ten thousand for each of these!” she says, as she points to a spread of prints in her book. She points out another print: “We had to pay P30,000 to the collector to use this,” she shares. Yet there are also generous souls, donating artifacts and restoration professionals who donate their services to the museum, and that makes her very glad.

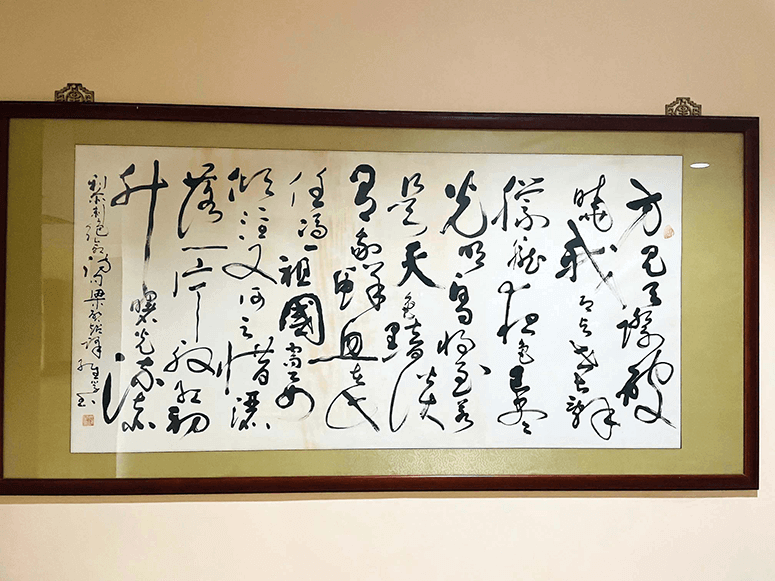

She gives me another book as a parting gift, Sining ng Pakikidigma ni Sub Tzu (The Art of War translated by Fernando Ang, Sr. She herself, Doreen Yu and others from around the world have contributed to annotating this book so relevant in these times with the Ukraine invasion and the Chinese threat against Taiwan.

But that’s a story for another time.