Heroes’ hearts and tokens of love

The story of the love token spans the ages and reflects the changing tides of the world’s fortunes.

For the conquering GI Joes who landed in Manila after the War, for example, it was chocolate boxes of Whitman’s Samplers, pink tins of Almond Roca and, of course, American nylon stockings. (These were the 1940s precursor of today’s gifts of Royce truffles, Victoria’s Secret and the more uppity La Perla lingerie.)

When the world was still filling concert arenas, the currency of romance next became candlelit dinner for two followed by backstage passes to see BTS.

Today, it’s all about the life-saving appeal of a pricey KN95 from Kaze and a slot to get a booster at a private company clinic. How the mighty have fallen — there used to be a time when a socialite could walk out on her nearest and dearest for lack of the exactly right Hermès crocodile handbag.

In the 19th century, that gilded age inhabited by our favorite heroes, it was, of all things, the opening of the Suez Canal which had the most profound effect on the rituals of courtship. That tiny tweak to the world’s geography cut travel time between Europe and Asia so drastically that it opened the floodgates to young, wealthy Filipinos to be educated in Paris and Madrid and — traveling in the other direction — the arrival of all kinds of imported delicacies that they would learn to consume.

Rizal, on the other hand, was the ultimate beau and his personal history is littered with women that he pursued.

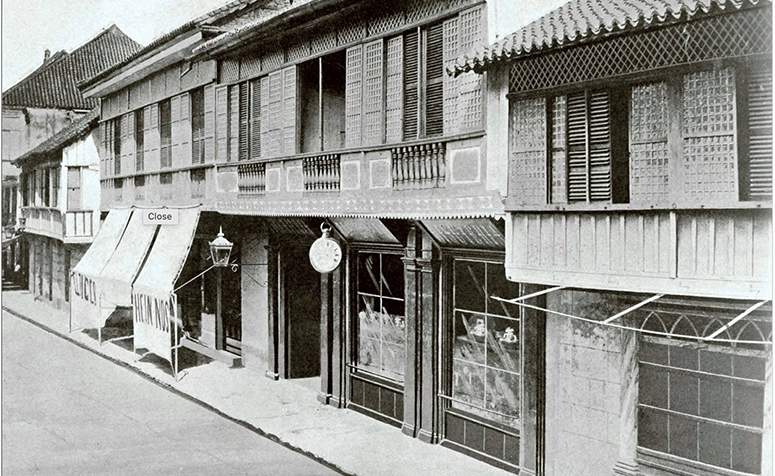

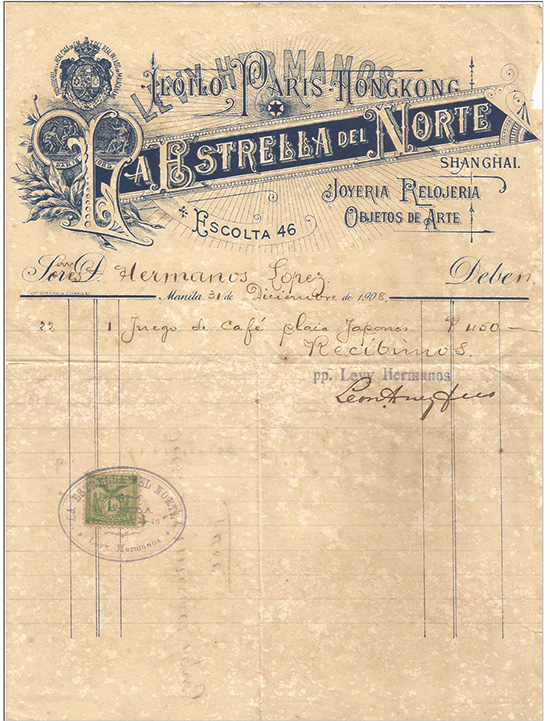

Social raconteur and collector of century-old culture Augusto “Toto” Gonzalez III said that the place to scoop up these bibelots for one’s beloved was at the posh La Estrella del Norte on the Escolta.

One of its most famous customers was His Majesty the King of Cambodia Norodom I, who arrived in Manila in 1872 on a grand tour. He promptly fell in love with the beauteous Josefa Roxas y Manio of Calumpit, Bulacan and felt that he had to impress with the right adoring message.

For her, he bought the “Granada de Oro,” a solid nugget in the shape of a pomegranate and studded with diamonds and rubies. La señorita Josefa would eventually donate this egg-sized jewel to grace Our Lady of La Naval at the Santo Domingo Church where it would enter the private collections of the cloister and disappear from public view.

What does appear on record is a companion piece called “La Concha,” a shell-shaped pendant confected for Josefa’s sister Ana and equally covered with precious stones. It bears an engraved inscription from the king as proof of his devotion to the family.

There were other jewelers who served the denizens of Manila’s high-society street called R. Hidalgo (later to be named Calle San Sebastian).

One of the most prominent was the Joyeria Paterno run by the talented family’s sisters. They would routinely submit award-winning designs for chokers and diadems to the famous Spanish expositions of 1880s, notes Gonzalez, thanks to the high-flying connections of the stylish Don Pedro Paterno who maintained a three-story townhouse in Madrid to house his private collections, including one of pre-Spanish gold jewelry.

It was the golden age of jewelry after all, says Gonzalez, between 1875 and 1899, and the bespoke ateliers of the Quiapo guilds were kept busy fashioning jewels for the wives of the Filipino and Spanish grandees.

Along with the arrival of European luxury goods came all manner of cosmopolitan entertainments. French opera companies arrived, for example, with their own coterie of seamstresses trained in the Parisian arts of dressmaking.

“For women of the time, however,” adds Toto, “it was not just the designer frocks but the sparkling suites of jewelry that was the measure of a woman.”

Gonzalez notes that Manila had its own share of fashionable flower shops. The most prominent was one owned by Regino Cortez of Singalong, a painter in oil who also happened to be a talented horticulturist. Cortez would supply bouquets and garlands ordered by the swains of Manila’s upper crust. He was also sought-after to decorate the legendary dinner tables of the Zobels and Ynchaustis. Imagine him as the Mabolo or Rustan’s Flowers of a century earlier.

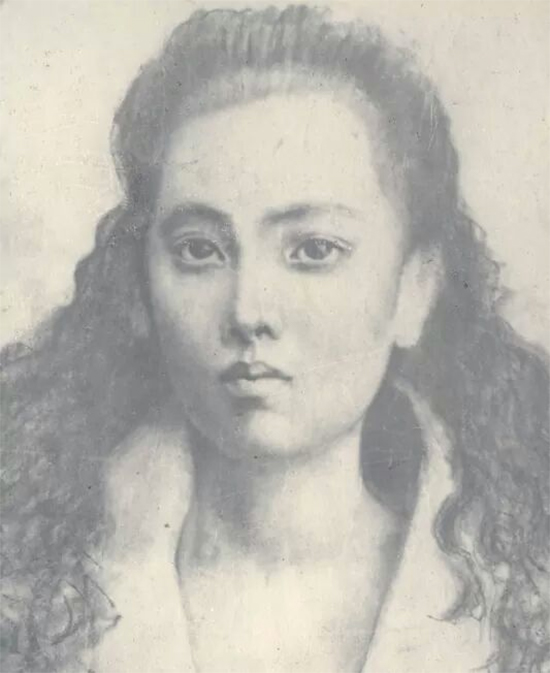

Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo had his own muse, the controversial Maria Yrritia, portrayed as a wood nymph in the magnificent record-breaking “La Inocencia.” Gonzalez harrumphs that despite her raven-haired beauty, she was not exactly a lady with a lineage. This prompted Hidalgo’s mother to close her doors — and most certainly her hoard of Padilla rubies and emeralds — to her.

The trial of Juan Luna is an eye-opening world of French courtship among the world of the demi-monde. He would testify that his wife’s paramour, a certain Monsieur Dussaq, would give her presents of eyeshadows and pencils to line her lids and color her brows.

Rizal, on the other hand, was the ultimate beau and his personal history is littered with women that he pursued.

He came closest to marrying two of them. First was Leonor Rivera — who supposedly had herself buried in a silk skirt that had his letters sewn into the hem. (Her mother had intercepted Rizal’s love letters to prevent their relationship from going any further. Leonor would discover them only after she had been married off to the British railway man Charles Henry Kipping.)

The other one that got away was the half-European heiress Nellie Bousted who he renounced because he could not give her the gift of his conversion to the Protestant faith that her mother demanded. (No matter, he managed to finish writing the Fili in the Bousted’s lavish villa in Biarritz.)

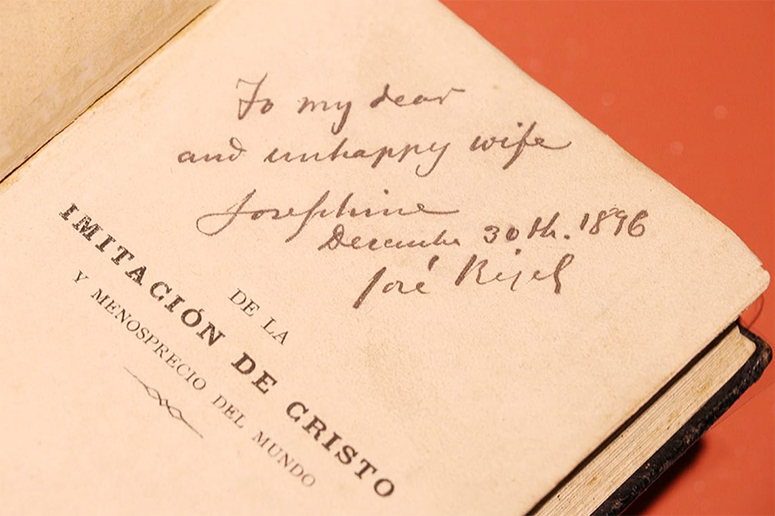

A man of letters, Rizal would use his talent for writing to woo his various intendeds. At the end of his life, he would send the ultimate offering: a copy of “The Imitation of Christ” by Thomas à Kemp, dedicated, on the last day of his life, “To my dear and unhappy wife, Josephine Bracken.”