For Fernando Zobel, order, like light, was essential

Showing at National Gallery Singapore until end of November, Fernando Zobel’s “Order is Essential” is a wide-ranging sequel to the exhibit in Madrid last year during the painter’s centennial, and the recent Ayala Museum retrospective.

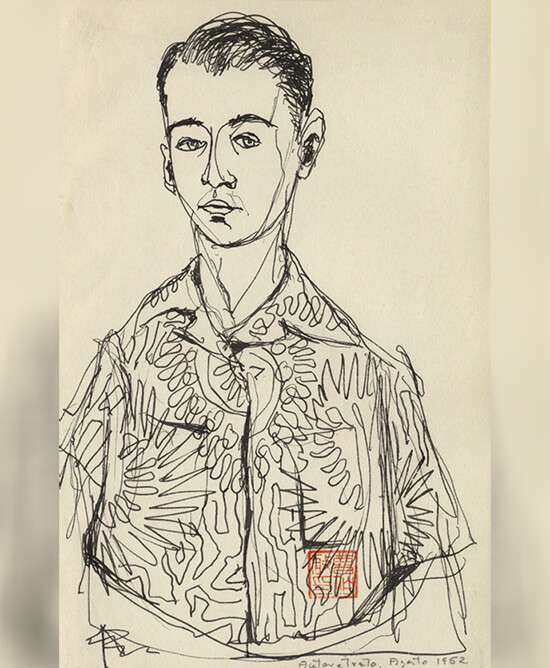

A main group photo shows Zobel and his peers during the abstract expressionist and modernist movements; future national artists Jose Joya and Hernando Ocampo are there, with Zobel standing far right, a smile on his face reflecting half of his haunted monk’s life.

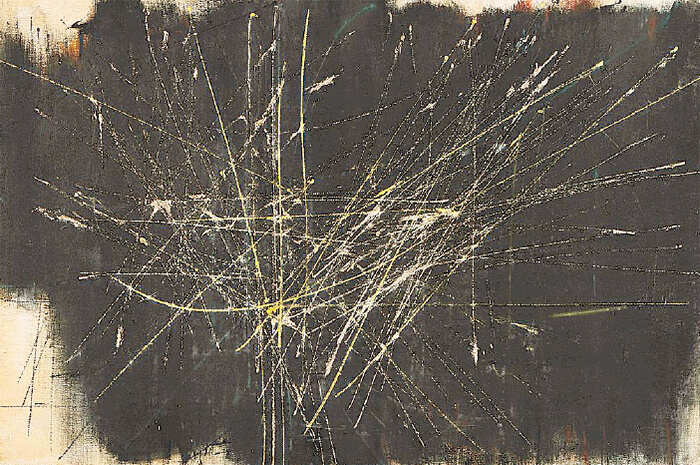

There is a generous collection of his Saeta series, the painter’s experiments and expositions with lines and grids almost like maps of cities; an untitled piece in orange and black suggests use of a syringe to control the outlay of lines, and also makes us appreciate simple tools like the pencil, ruler and masking tape in making art.

“If you look at Fernando Zobel’s artwork, you can see how he uses lots of different lines,” reads the show’s pamphlet. “He loved to experiment and believed that every mark meant something. His drawings and painting weren’t random—they were thought out carefully…. Do you think he painted them quickly? He didn’t. He actually planned everything out first. He did lots of sketches before creating the final artwork which he painted according to plan.”

Under glass case in the gallery are excerpts from an interview where the painter answers questions on his philosophy of art, his responses typewritten: “I have no philosophy, at least not consciously.”

Asked what he is trying to say in his work, Zobel answers: “It is not as yet clear to me. All I know is the pleasure I get from painting; from solving a difficult problem; from putting order out of chaos.”

“Who are the people (not necessarily artists) who have influenced your life, your work?” Zobel mentions Picasso, Matisse, the Boston painters who taught him how to paint just by looking at them, Jack Levine, Reed Champion. “I like their technical ability; their apparent clarity in expressing their ideas.”

He says the Spanish School also influenced him, in particular the Las Pinturas Negras, painters such as Goya, El Greco, Solana and Bosch, “but these have not influenced me technically.”

Also encased in glass are a number of syringes used by the artist in his paintings—without the needle, of course—emitting a strange light.

A wall in the gallery is devoted to paintings of footballers, a sport beloved in Spain with its La Liga and other minor leagues. Zobel gives ample tribute with his figures on field, somewhat blurred in the quickness of motion. The painter once mused: “I suppose that the distinction between action painting and the kind of painting that attempts to analyse movement is a subtle one, but it does exist.”

In 1966 Zobel’s Museo de Arte Abstracto Espanol was opened in Cuenca, situated on a cliff along with other houses collectively known as Casa Colgadas, or Hanging Houses.

“During his time in Cuenca, Zobel created work sensitive to what he saw around him: the gorge that he called ‘La Vista’, the houses in the valley, the plateau, and the Jucar and Huecar rivers and their banks. From this suite of works emerged two series, ‘La Vista’ and ‘Serie Blanca,’ significantly monochromatic investigations conflating figure and ground; space and metaphor; ether and stain.”

Zobel was also fond of incorporating text within the painting, such as the handwriting seen on the lower right-hand side of a painting, while above it loom layers of light and shadow prefiguring 3D, suggesting nudes and the chrysalis of found wings, in a gallery close to the equator, where order, like light, is essential.

Co-curators Patrick Flores and Clarissa Chikiamco believe, and rightfully so, that the rest of the world should know about Fernando Zobel, and are presently working on a reader of the painter’s articles, hopefully out before exhibit closes later this year.