The shape of feeling: Abstraction at the Spectacular Mid-Year Auction

When viewers chart the rise of Philippine modernism, they inevitably follow the restive itinerary of abstraction. From buoyant gesture to meditative monochrome, Filipino painters have taken non-representation as a route back to its emotional engine. Where Western modernists often raced toward purity, local abstraction lingers on lived experience—distilling city noise into streaks of charcoal, or the memory of a fiesta into tremulous planes of color. The reward is a refreshed perception of the world’s elementary hues, silhouettes, and textures.

That arc is on vivid display at the Leon Gallery’s Spectacular Mid-Year Auction, which drops the gavel on June 7, 2 p.m., at Eurovilla 1 in Makati City. Marking its 15th year in business, the sale presents 166 lots, which include works that map the nation’s non-figurative inheritance. “A decade and a half have passed since we first leased that space in Corinthian Plaza and officially engaged in the dynamic business of art,” recalls founder Jaime Ponce de Leon. “The rest, as they say, is history—experiences and turning points we continue to cherish.”

Four canvases by Fernando Zóbel headline the roster. Versión en Toledo (1975–77), painted in Cuenca during the gestation of his Museo de Arte Abstracto Español, is a luminous square in which ink-fine lines form a portal around an ochre blaze. Its studied hush is answered by Variante sobre un tema de Cassatt, a conversation with Impressionist Mary Cassatt in which slate-gray planes joust with a central flare of light. Collectors wanting deeper immersion can head to Zóbel’s retrospective, Order is Essential, which runs at National Gallery Singapore until the end of November.

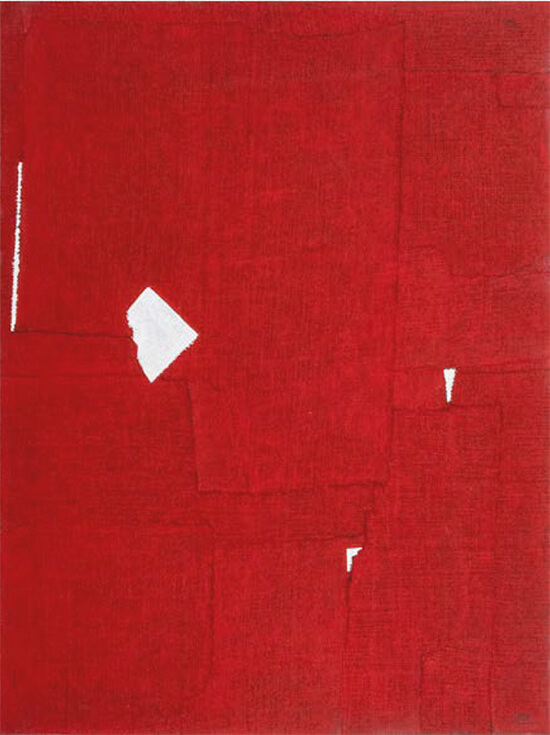

The roll of National Artists extends the story. Arturo Luz turns geometry into poetry with Nikko Revisited, overlapping burlap fragments stained crimson and edged with whispers of white—an echo, perhaps, of the vermilion torii that stride through the Japanese mountain town. José Joya’s Bird Song responds with acrylic collage: long, feather-like shards swoop across the surface, their syncopated rhythm reflecting his love of jazz percussion. Where Luz corrals energy into crystalline order, Joya coaxes music from the medium itself.

Two heirs to this lineage, Lao Lianben and Gus Albor, refined their vocabularies under Florencio Concepción—himself represented by an austere late-period canvas. Lao pares his painting down to vaporous grays punctuated by a single calligraphic stroke, borrowing from Zen practice while retaining a distinctly Filipino sense of earth and sky. Albor, by contrast, maps the metropolis: scaffold-like grids and misted pigment hint at flyovers, footbridges and sodium-lit nights. Together they show how abstraction can shift from metaphysical reverie to urban reportage without losing coherence.

Among today’s practitioners, Bernardo Pacquing stands apart, his voice represented by five canvases that double as metaphorical archaeological sites. In Under Squinted Scarf Joint No. 05, rectangles of pigment are floated, scored and partially erased until the surface resembles a billboard weathered by torn posters. The apparent informality masks strict choreography: every mark records an impulse accepted, resisted or revised, rendering the work both battlefield and diary.

Taken together, the non-representational lots at the auction compress a century of experiment into a single afternoon. They demonstrate how one generation hands its questions to the next, asking not what a painting should depict but how sensation, memory, and doubt might inhabit two dimensions. When the gavel falls, a new chain of private ownership will begin, yet the conversation—the ongoing effort to extend the language of Philippine abstraction—promises to remain gloriously unfinished.