How Filipino art blew up in the new millennium

Yes, 2020 did put a full stop to museum trips, auctions and art fairs in the Philippines. Yet it’s worth noting that the first two decades of this century have already seen incredible growth for Filipino artists — from the rise of art fairs and sellable “art toys” to “auction darlings” like Ronald Ventura, art has become both more collectible and more widely accessible to the masses.

In The Art and the Times of the New Millennium (2000-2020), volume two of the Atencio-Libunao Art Collection series put out by Januarius Holdings Inc., writers Lisa Guerrero Nakpil Tina, Arceao-Dumlao, JJ Atencio and others examine how the dynamic has shifted in the Philippines amid technological change, booming population and global warming over the past 20 years.

You could say the “moment” that brought it into focus was the return of the Philippines to the Venice Biennale in 2014, after a 50-year absence. Or maybe it was the first $1-million sale of a Ventura work.

More than ever, art is about two seemingly warring impulses: the commodification of art, shown in spiraling prices for “star” artists, and a more democratic impulse, exemplified by Banksy’s street stencils

More than ever, art is about two seemingly warring impulses: the commodification of art, shown in spiraling prices for “star” artists, and a more democratic impulse, exemplified by Banksy’s street stencils (but earlier predicted by Warhol and his endless silkscreen prints). Art was always heading in two directions simultaneously. Now the mashup continues.

In the opening essay, Lisa Guerrero Nakpil points to the rise of art fairs and a wildly booming pre-pandemic art market as proof that art has crossed over to the worlds of pop music, big finance, charity and politics. (Well, one could look at the Renaissance and its Medici art patrons for prior examples of this.)

More importantly, fame has become a driver for art’s acceptance by a more democratized world thanks to widespread pocket technology. Our phones are our gallery portals.

An opening essay focuses on Ventura, for his masterful form and melding of pop, Filipino culture and political messaging. Then there’s Jose Tence Ruiz, who led the Philippines back to Venice with “Shoal,” an installation meditation on Philippine sovereignty, the rusting BSP Sierra Madre “guarding” the disputed Scarborough Shoal represented by the artist as a dilapidated vessel, draped in red velvet — a bold, colorful reentry to the world’s art stage.

Tina Arceao-Dumlao’s essay looks at the economic lessons from 2000-2020. With phrases like “Build Back Better,” Filipino optimism marches on. But artists like Mark Justiniani force us to look a little closer in works like “Monumento,” with its man perched on a streetlamp, or his mirrored infinite spaces.

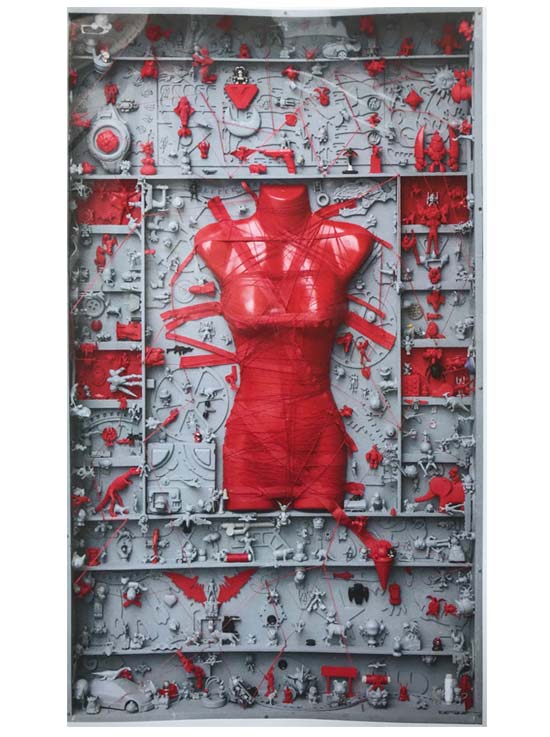

Meanwhile Mimi Tecson’s collage “Sulsi (Mended)” eerily predicts the colors of the coronavirus itself in her assemblage of painted toys, torsos and gadgets deployed amid a gray field and red paint accents.

JJ Atencio’s “The Fourth Industrial Revolution” looks at our information age, of course, and how principles of online consumption — blockchaining, e-commerce, A.I. — will, or could, apply to future art.

Alya B. Honasan’s essay “Global Warming, Consumerism and Going Green” explores the theme of sustainability in a 20-year span of alarming population growth and climate change, citing the Erikson Arcilla work “PEDXING,” with its perilously suspended stoplight and engulfed pedestrian sign swamped by a massive blue tsunami and less-than-comforting stormy skies behind. Meanwhile

Ram Mallari Jr.’s steampunk mixed-metal assemblages comment on the waste and floating detritus of our modern world, swept up in debris. (“Steamy R2D2,” “The Gypsy,” “Da Vinci”).

Jerome Gomez focuses in “The It Girls” on what our fixation on Filipina Instagram celebrity all meant (a battle between Rogue and Esquire over an Anne Curtis cover shoot in Paris, it turns out).

While that may seem like a watershed moment, there was still Instagram-for-all, #MeToo, and a (too-self-)conscious turning away from social media. Oh, and the Kardashians cancelled their own show.

With the Philippines’ fresh population turnover, the young and the restless will continue to push the narrative envelope. There’s Gromyko Semper, whose works like “Loco-Motive” and “The Allegory of Vision: The Viewing Room” consciously echo Brueghel and Rubens, Grecian ideals, Magritte and Pop art.

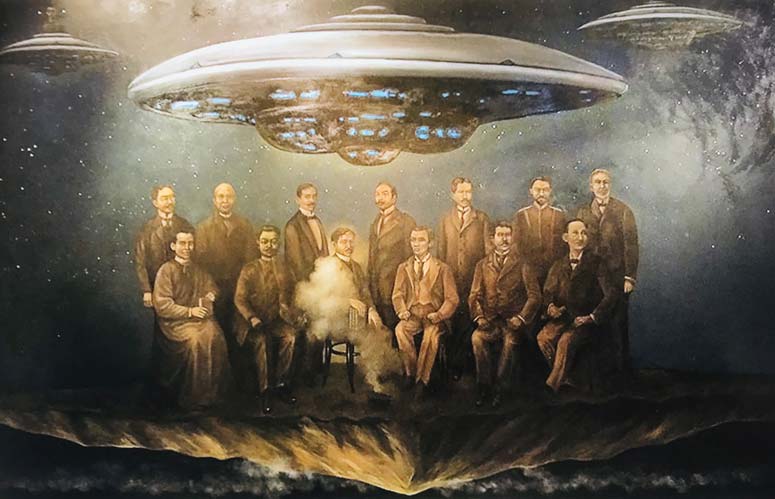

And there’s the much-seen large canvas by Kalye Kolektib (Street Collective), “Rebelayson (The Revelation),” which posits that the Philippines’ mythic founding leaders must have come from alien intervention (at least, judging from the current crop of less-than-stellar leaders). It closes out the book with a look back at Filipino history that also aims forward to sci-fi future.

But it’s Anish Kapoor, one of the most visionary Asian artists of the 2000s, who provides the final epitaph on where we are: “The work itself has a complete circle of meaning and counterpoint. And without your involvement as a viewer, there is no story.”

This seems circularly self-evident, but also worth repeating. The artist must construct a world based on his or her initial involvement in that viewing as well.