The making of an icon

The Lenten season is upon us. These 40 days are a period of reflection—assessing the state of the soul, our relationship with God and with the world. Opportunities for prayer and pilgrimage present themselves. Some opt to go away on retreat.

Recently, one such retreat-workshop was made available to those whose charism seemed to lean towards the arts. It would be revealed that art would only play a small part in an exercise that was essentially spiritual.

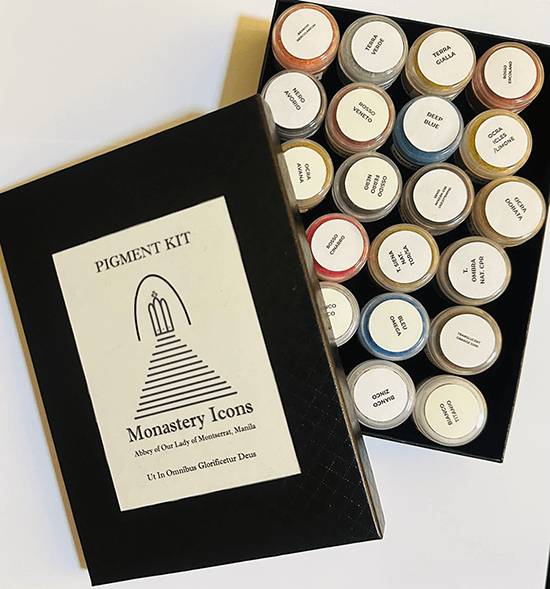

Through the efforts of the Benedictine monks at the Abbey of Our Lady of Montserrat, headed by Abbot Austin Cadiz, OSB, Russian iconographers Tatiana and Dimitri Berestov held two iconography workshops—one in Manila and another one in Tagaytay.

Tatiana and Dimitri are a married couple who have found their life’s calling in iconography. They are now based in upstate New York where they are instructors at the Prosopon School of Iconology. Living their teachings authentically, one notices that these teachers move with such tranquility, and even when tired, they still plod on with an ease of spirit that they almost seem to float.

The six-day workshop was about the process of making an icon—but there was a world of symbolism in every component, in every action.

The day begins with the solemn chanting of morning prayers, followed by a lecture-catechesis on the procedures to be done for the day. Silence is required during work, as it is a constant prayer. Sacred music is played as a gentle accompaniment throughout the day.

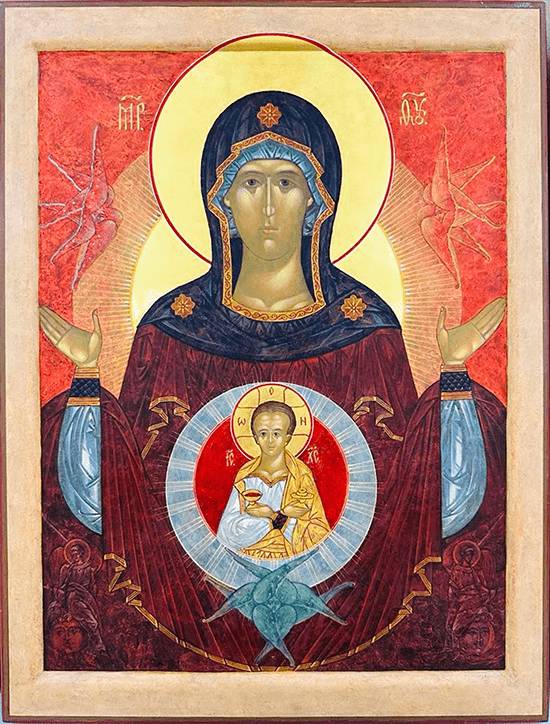

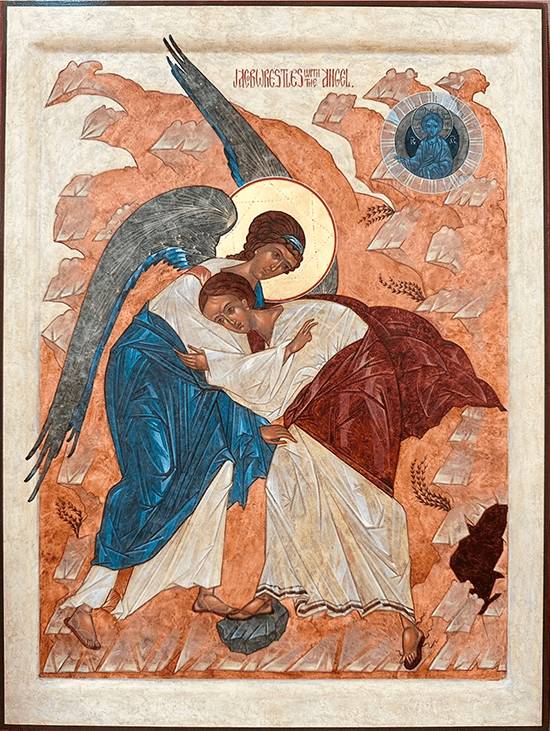

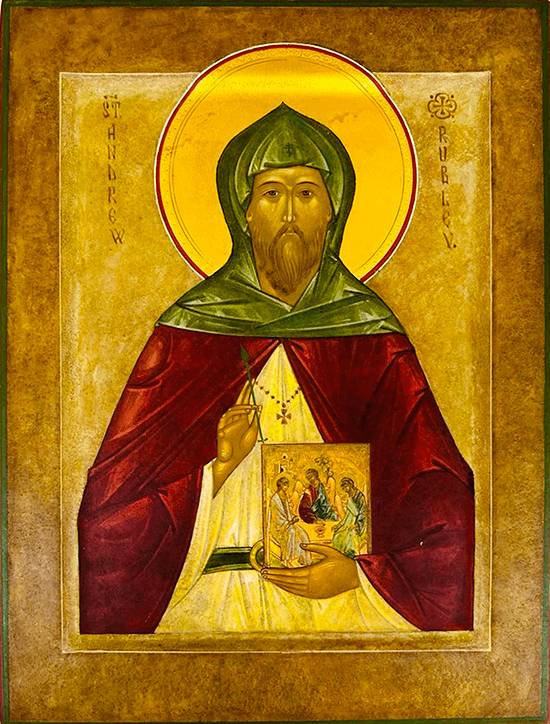

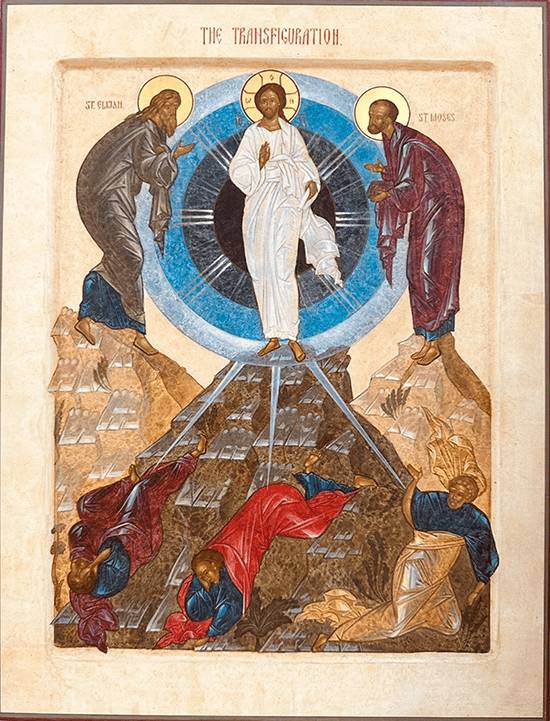

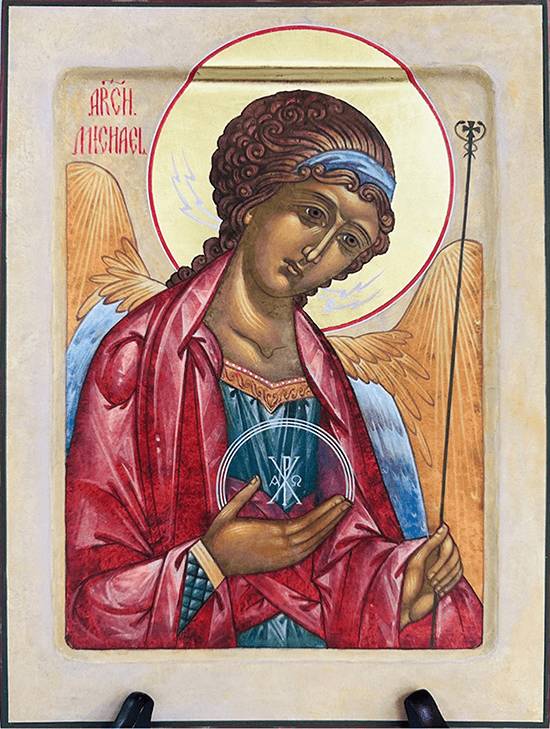

There are 22 procedures in completing an icon. It is, in fact, referred to as icon writing, and not as icon painting. The reason for this is because it is not a creative endeavor. The painter submits to centuries of tradition and to a process that requires a shedding of self. Iconographer Christine Hales explains, “Icons are meant to be Scripture in visual form.”

Beginning with a wooden board—there are vertical components and horizontal pieces that act as support-like braces—these remind us of the cross upon which Christ was crucified. The vertical reaches upwards toward the heavens while the horizontal represents how man carries his earthly cross.

The central portion of the board is also carved out to appear recessed. The difficult task of carving this out tells us about entering into one’s self—the inner chamber that no one sees. In the end, the shape also represents a boat, the Ark of Noah, where the center is safe.

There is a linen cloth that is laid on the board before it is covered in white gesso. The linen represents the shroud of Christ, while the smooth gesso (10-12 layers of it!) represents purity and quietude.

After tracing the image of the subject to be depicted onto the gesso, it is then engraved with a metal point. Then the halo is filled with red clay, sanded smooth, and a gold leaf is attached to it, using one’s own warm breath to provide just the right moisture.

The red clay represents man—the Adam of creation. The gold halo represents holiness and the breath reminds us of the Holy Spirit. The halo even extends to the frame, which means that the light must flow outwards to others.

Oh and the colors! How each one has its definition. The warmer colors of the rainbow—red, orange, yellow—are the earthly colors. The cooler colors are blue, indigo and violet and the celestial colors. The central color of green unites the earthly and the heavenly realms.

Therefore, the clothing of the subjects in the icon represents what they are and what they did in the world. Jesus, for example, in some icons has an inner garment of red (human) and an outer garment of blue (divine).

In applying the first layers of colors, let them flow naturally by “pushing the colors” gently. The more controlled finer strokes for the details also have meaning. If painting a coil, one first draws inward to get to the central point of truth, and once there, gestures again outward to do acts of service.

It can be observed that the images depicted in icons are never emotional. It is taught that they never have their mouths open. Their demeanor is generally serene even if grieving, angry or suffering. It is because they are all celestial beings who do not display earthly emotions.

They are also not made to appear as realistic portraits, but are heavenly images. Unlike artistic painting where light is reflected upon the subject, in icon painting, the light comes from within the subject. That is why an artist must change his mindset when writing an icon.

Icon writing changes one’s way of seeing. But because it encourages self-reflection and prayer, it also holds the promise of changing one’s heart.

In the end, one is struck by what Tatiana said: You don’t have to be an iconographer but your life can be an iconography.

* * *

Heartfelt thanks to Fr. Maurus Cuachon, OSB, and Dom Francisco Ma. V. Ramos, OSB, for the photos and assistance extended. For information, call or SMS 0929-8289017, or email prosoponphilippines2024@gmail.com.