The art of Nonoy Marcelo: Calling for more social critiques in meme format

Severino “Nonoy” Marcelo’s work often appeared daily in newspapers as a two-by-six-inch comic strip, no bigger than an average hand. But the role of these unassuming artworks are actually colossal and deeply important for the growth of the Filipino as a people.

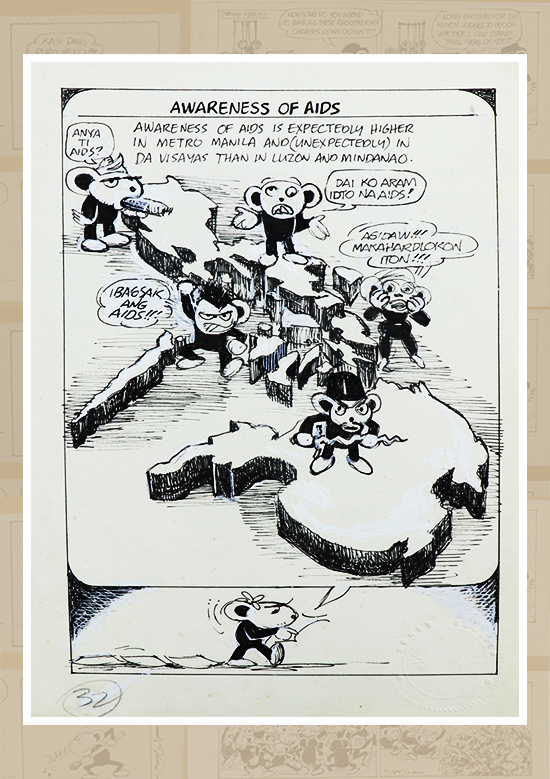

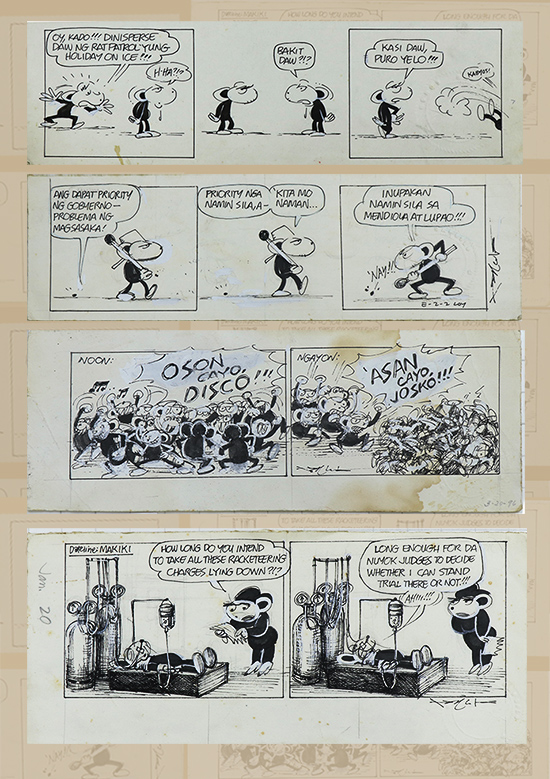

With the elections less than a month away, we are flooded with internet memes that appear in a similar format: one-line jokes over a viral image, or short bursts of cleverly edited videos. Like these memes on our feeds, Marcelo tackled the nation’s most important issues through his comic strips. By sneaking in his truths through humor, he did more than entertain: the laughs from his readers stood as acknowledgments of the difficult matters otherwise too uncomfortable to think about.

From the 1960s up until his death in 2002, his work delivered precious wisdom to the most common Filipino. Disguised as jokes, he bared the Filipino’s tendency for irrationality and pomposity regardless of political side. The characters in Ikabod Bubwit, Tisoy and Plain Folks held up a mirror to Filipino society as we dealt with the darkest events in our history: martial law, episodes of terrorism, the tragedy of MV Doña Paz and Ozone Disco, to mention a few.

It was in the school paper, The Advocate in Far Eastern University (FEU), where Nonoy got his grounding as a political cartoonist. Marcelo made weekly editorial cartoons and comic strips that developed his social awareness and skill for satire. He became famous for a cartoon character called PTYK, a long-haired beatnik who carried around large books and quoted Albert Camus or Jose Garcia Villa in a casual quip. In the few years that Marcelo was in FEU, PTYK became the conscience of the student body. The university archives record Marcelo’s mind as he observed and dealt with matters inside the campus: he showed high regard for FEU but did not hesitate to criticize any pretentiousness in the school culture.

Marcelo was plucked out of college when he was recruited to work as an artist for the Manila Times, although his education did not stop there. At every chance, Marcelo studied his world manically. His “lungga” (as his friends call his home studio) was a chaos of cigarette butts, sheets of papers, interspersed with the essays of William Henry Scott and Friedrich Nietzsche, and a slurry of article clippings from magazines that fed him world views. Journalist Howie Severino said in an interview that his sense of kapwa, or openness to society, was what fueled his creativity: “These imagined worlds that he created in his cartoons, they were all based on real life. He was very immersed in this kind of social research — observing people, talking to people, and absorbing all of these influences that were stimuli to trigger ideas.”

As a scholar of his books and of his world, he created his art with a deep understanding of Philippine politics, history and culture. He used this research to create a brand of humor that encouraged a perception of humanity that is innately flawed, yet effortlessly endearing. In the end, Nonoy Marcelo left a more mature nation — a tad more self-aware and more able to deal with its own mistakes and disappointments.

Today’s fight against disinformation begs the same feat from our intellectuals: to step out of their echo chambers and distill complex socio-political facts into formats that are accessible to plain folks; to deliver wisdom directly, tenderly, to where it matters, not only for this election season, but for the long term.

* * *

An exhibition titled “The Brave Bubwit: Nonoy Marcelo’s Irreverent Art that Attacked and Endeared” was held virtually on Far Eastern University, Manila’s Facebook page. The exhibit looked back at Marcelo’s major career milestones as an artist. It featured original drawings from the private collection of Atty. Saul Hofileña Jr. and selected works from the archives of Far Eastern University’s The Advocate.