How Lenten 'pabasa' has changed over the years

Long predicted to die because younger generations consider it archaic and out of step with the times, the pabasa has proved doomsayers wrong. Even Filipino migrants have brought it with them to the United States.

A centuries-old Lenten practice unique to the Catholic Church in the Philippines, pabasa literally means “reading”; it is a marathon communal reading of the passion story that usually lasts for an entire day or more.

Pabasa today

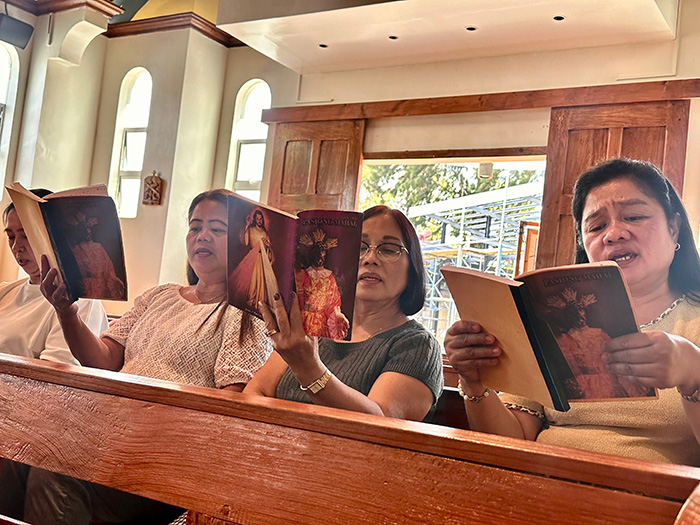

At a huge outdoor tent in front of the parish center building of the Minor Basilica of St. John the Baptist in Taytay, Rizal province on Holy Monday (March 25, 2024), women started to gather at 9 a.m. to do the traditional pabasa, a collective sung reading of the life, passion, and death of Jesus Christ.

Not too far from the basilica, at the social hall of the Grand Monaco Heights Subdivision also in Taytay, residents gathered also on Holy Monday to perform the pabasa for the entire day.

The private village is part of the St. Arnold Janssen Parish, but the pabasa was the residents’ own initiative.

“The Catholic community here is active and dynamic,” said resident Ronald Rey Espartinez.

Although Taytay is fast urbanizing, it’s still considered rural compared with Metro Manila.

But at the parish social hall of the Saints Peter and Paul Church in Poblacion, Makati, amid the rows of ritzy cafes, hotels, and office buildings, parishioners also held a pabasa.

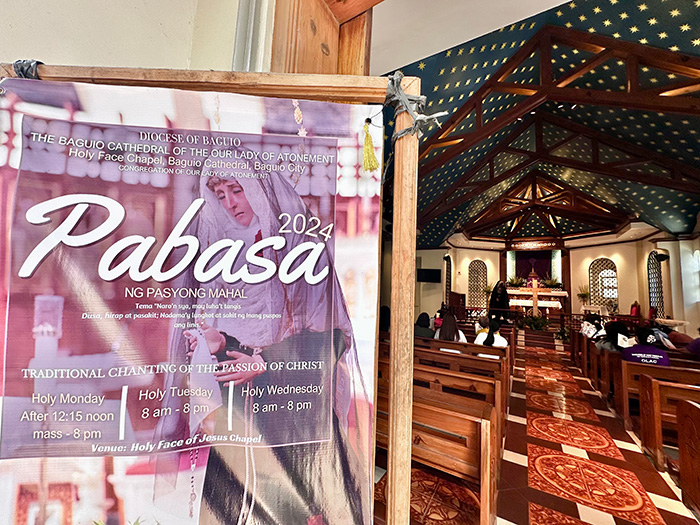

And at Ayala Center, the tony hub of European and American luxury lifestyle brands in Makati, the practice was performed not only on Holy Monday but also on Fig Tuesday and Spy Wednesday at Our Lady of Hope chapel in Landmark.

Chaplain Fr. Reginald Malicdem said the shopping center is surrounded by residential villages and condominiums. “So, this tradition that is usually done in parishes is being brought closer to the people who live near the shopping malls,” he explained.

Across the Philippines, the pabasa and other Lenten practices have enjoyed a resurgence after the protracted lockdown as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Philippine Lenten tradition has also been brought to the United States by Filipino migrants at the St. Raymond Church in Dublin, California, and St. Agustine's Church in Philadelphia.

All-time Philippine best seller

In pabasa, lectors read "Pasion" (later Filipinizied as "Pasyon") narratives written in octosyllabic verses that were composed during the Spanish colonial period, starting with the four “Pasion(s)” of the Tagalog region—the original “Pasion” by Gaspar Aquino de Belen in 1704, then those by Don Luis Guian in 1750, Fr. Mariano Pilapil in 1814, and Fr. Aniceto de la Merced in 1856.

Although poets and scholars generally rate De la Merced’s to be the best, it is the Pilapil version, Kasaysayan nang Pasiong Mahal ni Jesuchristo Panginoon Natin na Sucat Ipag-alab nang Puso nang Sinomang Babasa (Narrative of the Holy Passion of Jesus Christ Our Lord Which Will Greatly Inflame the Heart of the Reader), that is the most popular.

More popularly called “Pasiong Genesis,” since it starts its account of salvation history with Adam and Eve, Father Pilapil’s work continues to be printed today; it is arguably the biggest best seller in the country after the Bible.

Orality

Despite its alleged anachronism, why has the pabasa persisted?

Scholars have pointed to the Filipinos’ oral culture.

“The practice of singing out in lyric lines the lives of heroes and the recounting of strange and epic events is traditional in all the tribes of the islands,” wrote Jose Villa Panganiban, the late lexicographer and head of the National Language Institute, forerunner of today’s Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino, in “The Literature of the Filipinos.”

“With the introduction of the Catholic faith, the life and death of Jesus Christ being the theme of Lent … seems natural to be put into verse and chanted … for the edification of the people and for the fitting observance of Lent,” wrote Panganiban. “Thus, the Pasion (and its sung reading) came into being.”

As if to buttress the Filipinos’ penchant for orality, the Tagalog Pasion was translated into all the other Philippine languages Ilocano, Kapampangan, Bicol, and Visayan.

Performativity

The Pasion also became the “script” for the senakulo, the Philippine version of the passion play.

In Bulacan, the senakulo productions of Malolos, Hagonoy, Plaridel, and Santa Maria are eagerly viewed during Holy Week, according to Fr Nicanor Lalog III of the Diocese of Malolos.

In Cebu, the senakulo remains but it is known today as “Buhing Kalbaryo.”

“It is quite institutionalized in Cebu City by the government and in many parishes,” said Hope Sabanpan Yu of the Cebu Studies Center of the San Carlos University.

The word “senakulo” comes from the Spanish “cenaculo” or cenacle, which in turn is derived from “cena” or supper, in reference to the Last Supper, when Jesus instituted the sacrament of the Holy Eucharist, which commemorates his passion and sacrifice on the cross.

The staging of the Pasion via the senakulo should show how the Pasion has gone from orality to performativity, suiting the Filipinos’ cultural predisposition.

Social relevance

For historian and cultural scholar Reynaldo Ileto, the singing and staging of the Pasion across the centuries have so affected the Filipino psyche that they may have a bearing on popular liberation movements.

In his celebrated book “Pasyon and Revolution,” Ileto wrote that through the pabasa, the masses derived powerful and socially relevant meanings from the passion narrative that drove them to join social rebels, often quasi-religious figures themselves, to fight injustice by the wealthy and powerful.

Whether spiritually charged or politically potent, the Pasion, pabasa, and senakulo should underscore how Filipinos have made Christianity and Catholicism their own.

Filipinos have made them their cultural patrimony.

“The Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines encourages the perpetuation of these Lenten practices as intangible cultural heritage of the Church,” said Bohol priest Fr. Ted Millan Torralba, executive director of the CBCP’s Episcopal Commission for the Cultural Heritage of the church.

Sabanpan-Yu said the Cebuano passion drama “buhing kalbaryo” is not under threat as a popular expression of piety because of modernity and the younger generation’s loss of interest.

“It would however grow in relevance,” she said, “if it is artfully connected to the sufferings of our time particularly those that afflict the young such as gender confusion, pornography, human trafficking, internet addiction, lack of education, and poverty, as well as broader problems like poverty and global warming that afflict Cebuanos across generations.”