Men of the lunar moon: Art and artists from the heavenly kingdom

As the Year of the Horse clatters into view, the Celestial—or the 19th-century word for “Chinese”—empire has become increasingly controversial.

There’s been some nasty name-calling, including the newly minted phrase “Tsina-Dors,” a shortcut for “Tsina-Traydors” to describe those who take issue with the idea of the West Philippine Sea.

But as the South China Sea flows from one end of the country to the other, Filipinos will find, thanks to thousands of years of trade between the two countries, that Chinese DNA runs through many of our veins as well.

In fact, scratch some of our greatest heroes, and there is bound to be the hint of what the Spanish colonial registers would term “Sangley,” which translates to a sort of “frequent flier,” referring to travelers who came so often to these islands because they were in the business of an early form of import-export.

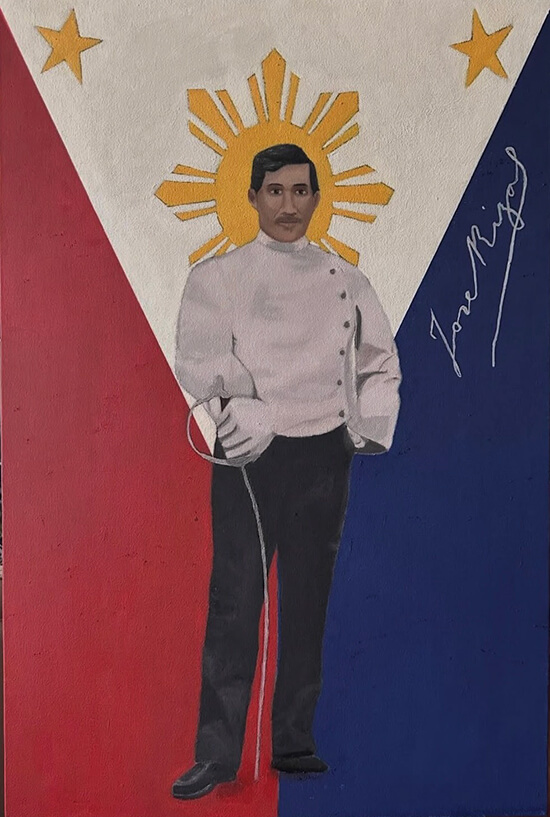

Our “First Filipino,” Jose Rizal—given that title by his biographer Leon Ma. Guerrero, because he was the first to imagine a national identity— was actually descended from a merchant from Jinjiang county in the city of Quanzhou, Fujian province. He was the “First Pinoy”—but also happened to be a fourth-generation Chinoy.

Quanzhou was famous as the first stop on the seaborne Silk Route, which traversed Southeast Asia to the Arabian Peninsula, carrying the civilized world’s finest goods. It fathered enterprising citizens, unafraid of finding their fortunes elsewhere. Rizal’s ancestor was originally known as Domingo Lam-Co (or “Cua Yi-Lam” or “Ke Yi-Nan” in Mandarin) when he arrived in the 17th century. He would eventually take the name “Mercado” after settling in Biñan. He was Rizal’s great-great-grandfather.

Rizal himself would put aside his own identity and take the name by which he is now best known. In a way, that re-birth represented his part of a greater movement called the ilustrados, who believed in the principles of the Enlightenment, of reason, and of the equality of all men.

Nevertheless, was it just an accident of geography that one of the centers of their discontent was Hong Kong, where Rizal would find refuge and practice as an eye doctor?

One of Rizal’s greatest admirers was Don Roman Ongpin, a wealthy Chinoy and founder of one of Manila’s biggest bazaars, “El 82,” an early form of department store in Binondo.

Don Roman would bring in paints and canvases for the elite, including the young Juan Luna and Resurreccion Hidalgo. When the Revolution broke out, he would use his trucks to smuggle arms and ammunition to the cause, hidden under his more innocent merchandise.

The Ongpins would form a familial alliance with Damian Domingo, considered the first artist to paint the Filipino everyman and his life, rather than devoting his talents exclusively to religious images and portraits of bishops and priests.

Don Roman represented a different face of the Chinese character, which had heretofore been dominated by enterprising men like Domingo Lamco—among them makers and doers like Telesforo Chuidian, Mariano Limjap, and Pedro Paterno (whose original ancestor was another self-made tycoon, Ming Mong Lo, or Molo). These men would use their fortunes to bankroll the Revolution and the First Philippine Republic.

The Confucian way, on the other hand, emphasizes scholarship, art and culture.

Confucianism views art and culture not merely as ornaments or circuses, but as tools for morality, social harmony, and even ethical conduct. This would be rooted in tradition, ritual (li), and the cultivation of virtue (ren), shaping a distinctive aesthetic in the arts, literature and music.

He would hand down this strict tradition, and his son Alfonso would become one of the country’s most learned collectors and art historians, amassing Rizaliana and paintings by Luna and Hidalgo, which he would carefully study and restore.

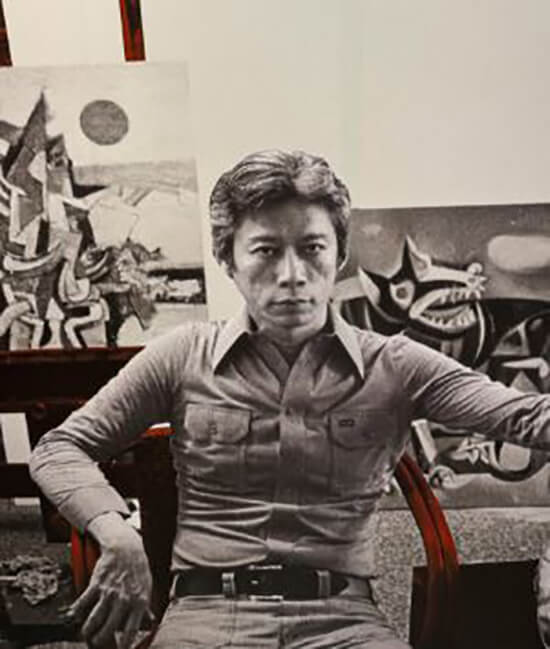

That thread would emerge again and again through the centuries. A hundred years later, one of the most important of the Filipino modern artists would be Ang Kiukok. Born in Davao City to Chinese immigrants, Ang Kiukok was christened with a bright, shiny, and optimistic name, which, in English, meant “Save the Country.”

There was always something high-minded and, yes, visionary, about him: An astonishing entry in his biography details that in 1956, he “stayed in Sulu for five years to teach art to children of Chinese descent.” When he was 21, he came to Manila and enrolled in the University of Santo Tomas College of Architecture and Fine Arts, where he met his lifelong mentor and friend, Vicente Manansala. It was here that he would forge bonds and mount exhibits at the legendary Philippine Art Gallery, the country’s first outpost for abstract art.

Influenced by his travels to the United States, where he famously beheld Picasso’s “Guernica,” he would use his art to tell the tale of the anguish of everyday life. He would remain inspired by the secret lives of his surroundings, cactus plants, open windows and street dogs, screaming silently at the status quo.

In July 1969, he took a break from the earthly and chose to record his impressions of the breathtaking moon landing with the work, “Man in Motion.” Neil Armstrong took that famous “first step for mankind” on the pockmarked Sea of Tranquility. (One can still gaze at it at Leon Gallery.)

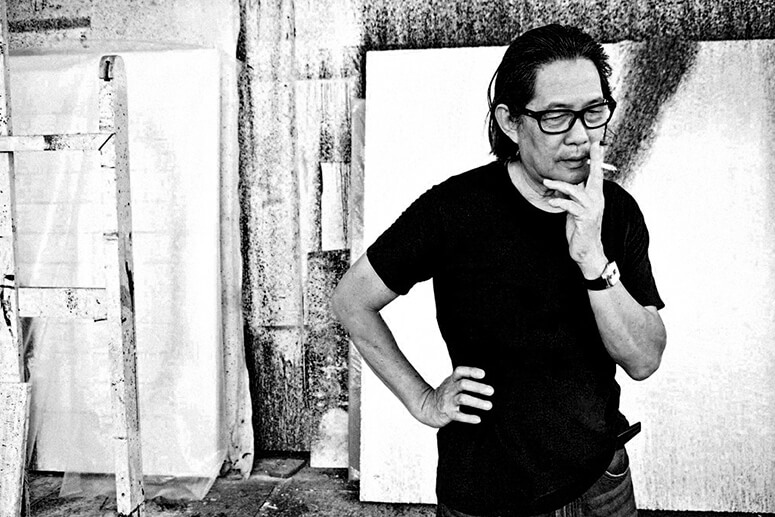

A generation later, another Filipino of Chinese descent, Lao Lianben, continues to embody Confucian values, championing harmony and balance. Nothing is ever extreme or askew in a Lao painting. Each work elevates the beloved Confucian concept of calligraphy, serenity writ large.

Drained of all distractions and choosing to paint in elegant monotones, Lao captures a universe that is both serene and abundant.

Younger Chinoys continue to draw deeply from that heritage. Sean Go is a Paris-based artist from one of the families that founded the first retail-complexes in the southern Philippines. He combines a quirky fascination with pop culture and fashion to create Godzilla-like monsters and fiery cartoon characters. (”Jurassic Kong” was the title of one exhibition he created.)

Go’s grandparents on both sides actually came to Manila in 1940, just before World War II exploded. He is, however, the first in his family to break with tradition and pursue art rather than business, despite having eight degrees under his belt.

He describes his “artistic methodology as a combination of cultural artifacts, ranging from children’s parables to biblical narratives. His canvases include Barbie and Lego, remixing them with Optimus Prime and Japanese anime, as well as his favorite Filipino food. Spray paint and crayon textures create “a calculated childlike tone.”

Joanna Ongpin Duarte, great-great-granddaughter of Don Roman and Damian Domingo, now takes us full circle: she considers both her eminent ancestors her inspirations.

Domingo was the master of the art form called “tipos del país,” souvenir portraits of Filipino men and women, from the high-born “gobernadorcillos” in top hats and ruffled shirts to sunburnt farmers and fishermen. Think of them as 19th-century Instagrammable records of life at the time. Domingo was said to be so adept at limning the finest details that he used a single sable hair for his paintbrush.

Joanna has continued this tradition, using a cache of rare archival photographs belonging to her great-grandfather. Drawing on her experience in designing children’s clothes, she has the same fine eye and attention to detail as her famous forebears.

It’s a world viewed through many lenses—just as our shared Chinese and Filipino heritage creates a wonderful mille-feuille pastry of many delicate layers. There are women smothered in lace, withstanding the heat of a summer’s day with a fan; young Turks in crisp, white linen suits; a chino chanchaulero, hawking black grass jelly; Rizal in a French fencing costume, épée sword in hand, ablaze in front of a Philippine flag.

These are scenes of a forgotten but magical life that continue to cross histories and generations as the most fascinating of art does. They will always remind us of one thing: that we are all, at heart, Filipinos.