Patriots, painters, princes: The Chinese in the Philippines

The sons of the Celestial Empire—or the Chinese—have had a long and varied history in the Philippines, coming much earlier than the Spanish and ultimately running in tandem beside them and to Castilian ruination.

They were the skilled artisans who created the sumptuous ivory statues of the Crucifixion and the Immaculate Conception that filled the Filipino churches, convents, and more palatial homes. (The Virgin Mothers at the onset would feature the same Asiatic eyes, long earlobes and clasped hands as the Buddha.) The Chinese would create marvels of wooden furniture without nails, altar tables covered in marquetry and inlaid with horn as well as beds festooned with pomegranates and pineapples which would reach their zenith under Isabelo Tampinco. Chinese painters are also said to have trained the eyes and hands of such remarkable painters as Jose Honorato Lozano and Justiniano Asuncion. They paved and tiled the great churches; and covered the floors of the cathedrals such as San Sebastian with herringbone parquet.

At the very start of the Philippine Revolution in 1896, the Celestials were quick (but quiet) in lending their support. General Santiago Alvarez in his memoirs of the Katipunan recounted that just a few days—on Aug. 26, 1896 to be exact—“after Bonifacio led the Katipuneros to signal the start of the Revolution in Balintawak, they moved to Mandaluyong where they were given by two Chinese stores ‘two packets of Insular cigarettes, two boxes of matches, five cans sardines and P5 in cash.”

Historian Milagros Guerrero would document the observation, “The Chinos have supplied the separatists with falsified stamps and seals of the government. (For this), the separatists have much to thank the Chinos.” These were indispensable, after all, to manufacture and replace the identity papers (torn up en masse in the Cry of Balintawak as a symbol of commitment to the cause) as well as to create papers for safe passage and the movement of troops.

The contributions came in from across the country from “Angeles, Malolos, Tayug in Pangasinan, Catmon in Cebu, Ilocos, Vigan, San Fernando in Pampanga, Samar, Iloilo, Masbate, Iba in Zambales, Tarlac, Apalit in Pampanga, La Union, Calumpit in Bulacan among others.”

Other reports of the time detailed their participation. “Aside from cash and other donations, the materials given included rice, oil, salt, dried pork, carabaos, and other food. In other cases, the Chinese helped solicit gunpowder, matches, pens and paper, clothing and hats, and medicine. There were also Chinese who helped transport the revolutionaries’ goods.”

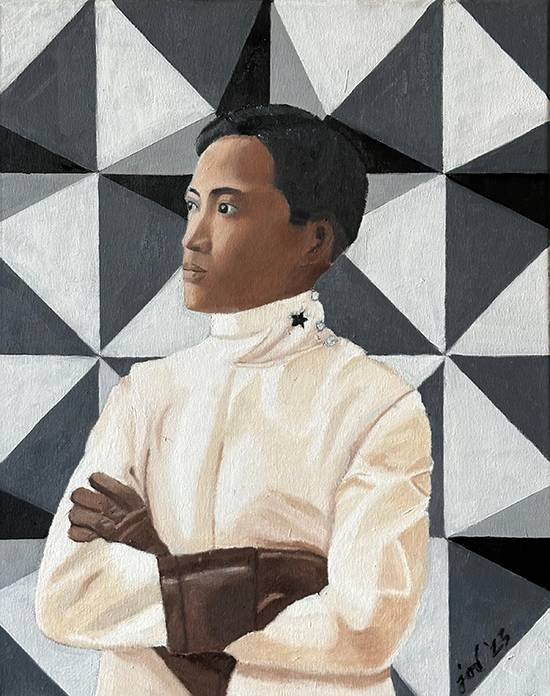

Roman Ongpin (1847-1912) had founded in 1882 Manila’s first art shop, called El 82 after the year it was established. El 82 would become a meeting place for the Ilustrados and after the outbreak of the Revolution, Ongpin would secretly support it, importing war supplies and delivering them in the guise of art materials. His son Alfonso would become an omnivorous collector of Filipino art and an avid Rizalista, modeling his life after our national hero. He would take up fencing, for example, because Rizal loved the épée.

Jose Rizal could trace his ancestry to an enterprising immigrant from Chinchew, by the name of Domingo Lam-co. He would have a son who would be baptized Francisco Mercado. The historian Austin Craig would say “he gave his boy a name which in the careless Castilian of the country was but a Spanish translation of the Chinese name his ancestors had been called. "Sangley," "Mercado," and "Merchant" mean much the same.”

Indeed, it was as the merchant-princes of the realm, however, that the Chinese-Filipinos would be most formidable. Men like Pedro Paterno (a third-generation descendant of a Chinese immigrant), Mariano Limjap, and Telesforo Antonio Chuidian were important men of substance. Presiding over vast fortunes built on property and enterprise, they controlled entire industries and various crops. Their children would continue to be not only immensely talented in business but also well-educated, highly cultivated personages, and collectors of the finest art and books. They would rise to guide the fate not just of the Revolution but also of the Filipino nation.

In the case of Telesforo Antonio Chuidian, his father was a successful merchant who originally came from Amoy (Xiamen). He inherited the family business in his teens upon his father’s untimely demise. He quit his schooling at the Ateneo de Manila to devote his energy full-time to business, setting up with Manuel Buenaventura the partnership Chuidian Buenaventura y Cia. It did a roaring trade, providing cash loans for coffee in Lipa and sugar in the rest of Batangas. Chuidian would become so successful that he would acquire several haciendas as well as numerous properties in Manila.

Chuidian, at one time, even asked his partner Buenaventura, a lawyer, to represent the embattled Rizal family in their land dispute with the friars. A son-in-law, General Jose Alejandrino, would recount that Telesforo was indeed the model for Kapitan Tiago, whose fabulous home was immortalized in the first chapter of José Rizal’s iconic novel, Noli Me Tángere.

With the outbreak of the Philippine Revolution, he was targeted by the Spanish’s secret police as a supporter of the Katipunan. He was imprisoned in Fort Santiago in a dungeon so dismal that water would be up to his neck during high tide. As a result, he contracted tuberculosis, which eventually led to his death, years after his release, in 1903. Family legend has it that he exchanged his freedom for a bayong (basket) filled with magnificent diamonds.

During the Philippine-American War, he became a member of the Malolos Congress and an important pillar of the First Philippine Republic. Along with fellow billionaires Mariano Limjap and Pedro Paterno, he wielded such influence and commanded such respect that his signature on the Republic’s paper currency guaranteed its value. For this and other acts of patriotism, he would again be arrested and imprisoned, this time by the American colonial forces. He would, on this occasion, be quickly released. Chuidian would become so disaffected, however, that he would leave the Philippines and retire in Europe.

As we celebrate the Year of the Dragon, we recognize the painters and princes—patriots all—who were truly great Filipinos.