Why Karl Lagerfeld is a controversial choice for the Met Gala

It’s Met Gala time again come May 1, and the fashion and celebrity world is abuzz about the theme and what to wear for what is arguably the biggest fashion event of the year to open the exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum for the benefit of its Costume Institute.

This year, the exhibit “Karl Lagerfeld: A Line of Beauty” is particularly fraught with controversy because the subject, who died in 2019, was legendary for his politically incorrect opinions, which were delivered with his typical acerbic humor that today’s woke generation does not find amusing at all.

On the issue of body positivity, he insisted on thin, sample-size models for the runway, saying, “No one wants to see curvy women,” calling Heidi Klum “too heavy” and Adele “a little too fat.”

Famously losing 92 pounds in 2000 to fit into Hedi Slimane’s impossibly skinny suits for Dior, he promoted the idea that dieters should embrace fashion and not health or wellness as a motivator: “There is nothing worse than looking longingly at clothes that you would like to wear but are definitely too tight for you.”

Regarding #MeToo, he practically defended the predators: “Why did it take 20 years for these starlets to remember? If you don’t want your pants pulled about, don’t become a model, join a nunnery!”

He didn’t even spare his fellow couturiers and artists, comparing Jeff Koons to a prostitute and calling Azzedine Alaïa “a designer of ballerina costumes for menopausal fashion victims.”

The Met organizers, however, chose to ignore whatever he had said and just concentrate on his contribution to fashion. Anna Wintour, Vogue editor-in-chief and chair of the Met Gala since 1995, said, “More than anyone I know, he represents the soul of fashion: restless, forward-looking, and voraciously attentive to our changing culture.”

He also has an unparalleled body of work from 1954, when he shared the Woolmark Prize with Yves Saint Laurent, another emerging designer then, until his death four years ago, creating collections for Balmain, Patou, Chloé, Fendi, Chanel, and his own eponymous brand.

His reputation for turning around the fortunes of musty brands was evident at Fendi where, from 1965 onward, he turned the Roman fur house into a ready-to-wear power player—conceiving the double “F” logo to represent “Fun Fur” since he refused to treat luxury pelts like sable too preciously by shaving them, dyeing them in multicolors and doing everything else to make them cool again.

He did the same at Chanel, which he called “an institution, and you have to treat an institution like a whore—and then you get something out of her.”

By bringing its old codes to the present with a healthy dose of irreverence and a punch of pop culture, he was able to resurrect Chanel from the limbo of irrelevance that relied on perfumes and cosmetics to survive.

In keeping with his unconventional ideas, Lagerfeld was actually against fashion retrospectives, recalls the curator Andrew Bolton: “Karl never tired of telling me that fashion did not belong in a museum. When we worked on the Chanel exhibition, he was incredibly generous with what he lent but was completely disinterested in the exhibition itself! He would say, ‘fashion is not art—fashion belongs on the street, on women’s bodies, on men’s bodies.’”

Bolton was entrusted to rein in the late designer’s output, which is prodigious, thanks to his workaholic ways, once saying, “I hate the word ‘vacation,’ it sounds like something empty.”

The curator was in a quandary at first but knew that “we could not do a traditional retrospective. For one thing, Karl would have hated that. Even though one of his facets was that he was a historicist, and would revisit themes in his works, he was always looking to the future in his own work—he hated looking back at the past. It was something he had a very conflicted relationship with.”

Bolton finally found inspiration during the designer’s memorial service at the Grand Palais, where the speakers included some of the premiers that Lagerfeld had worked with for years, including one from the Chloé years of the ‘60s to the ‘80s.

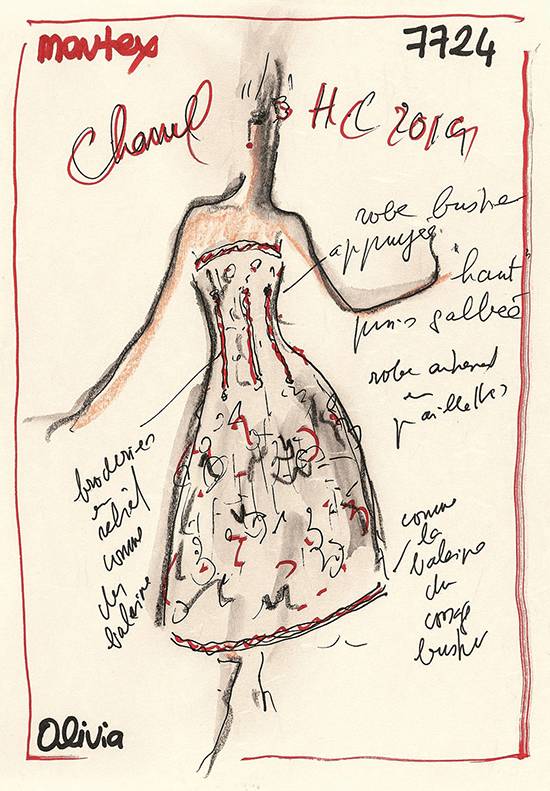

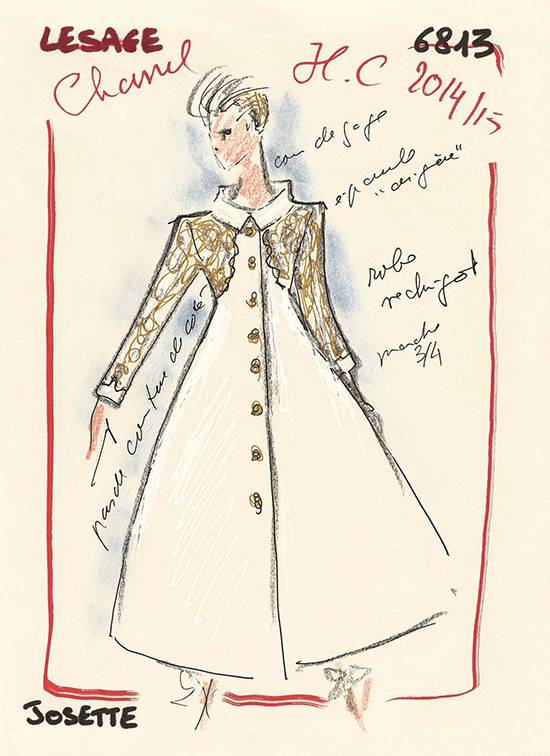

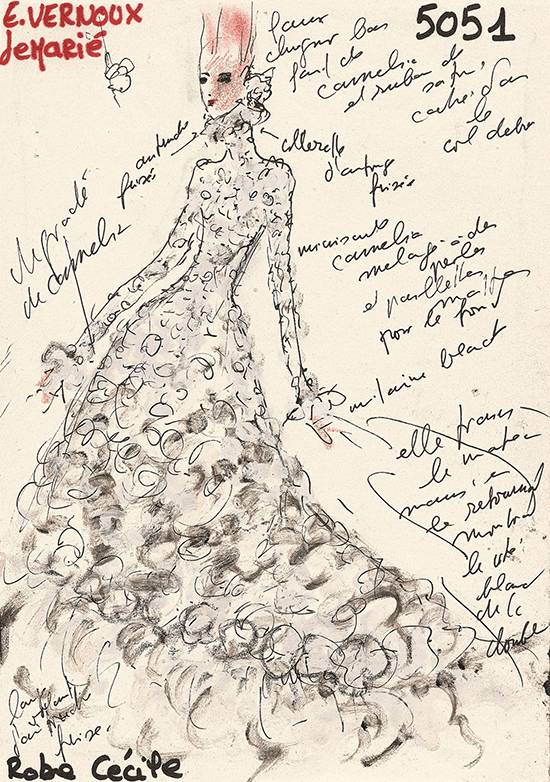

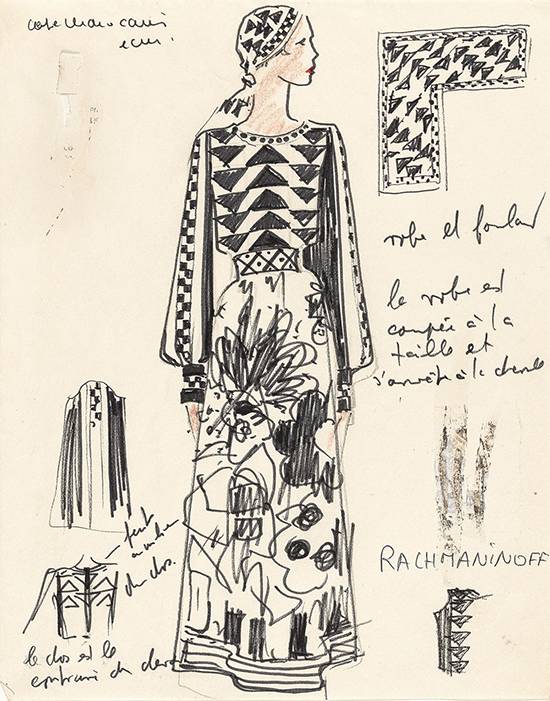

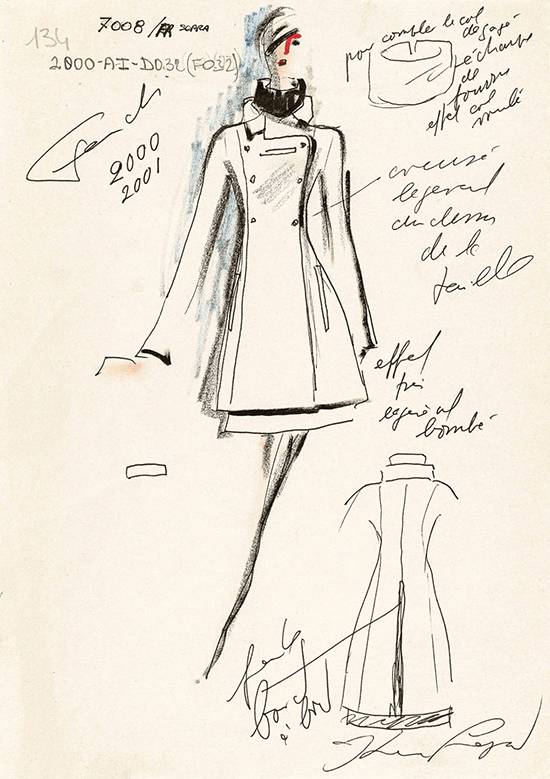

“These were the people he worked most closely with to translate his design into clothing. And they spoke of him with such love.” This led the curator to the key for the exhibit: Lagerfeld’s sketches.

The designer would sketch everything, saying he “could draw before he could talk or walk.” It was his tool for communication, whether by fax or iPhone.

“So at its heart, the exhibit will look at the evolution of Karl’s two-dimensional drawings into three-dimensional garments,” says Bolton, who was fascinated by the fact that the drawings—which look very spontaneous and impressionistic—are actually very precise, almost mathematical: “We can’t see it because we are not trained, but his premiers knew down to the millimeter what each line meant. It was almost a secret code, a language shared between him and those premiers, that only they could fully decipher.”

Visitors can look forward to seeing around 150 looks from all the houses where he worked, all presented together with the original sketches. Video interviews with his respective premiers, shot by the French director and writer Loïc Prigent, who also did The Legacy of Alexander McQueen, will give them a chance to crack the secret Lagerfeld code.

One more thing to anticipate is the exhibition design of revered Japanese architect Tadao Ando, who actually designed a house for Lagerfeld that was never realized but will include some of its elements in the exhibit.

What should be just as exciting for most people is the Met Gala that opens the exhibit. Are the Kardashians really banned and who will finally be invited? And how will the attendees honor the legacy of the late designer? Will they do archival or ask their designer to do their own take on his works, or maybe dress like Lagerfeld himself or look like his beloved Birman cat, Choupette?

Whatever it is, you can surely imagine Lagerfeld taking a quick look and having the snappiest bon mot to say.