Elsa Peretti: Tiffany’s designer of the sublime

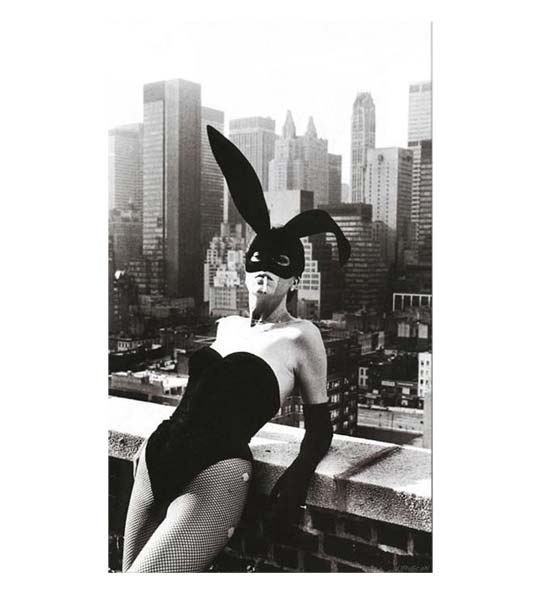

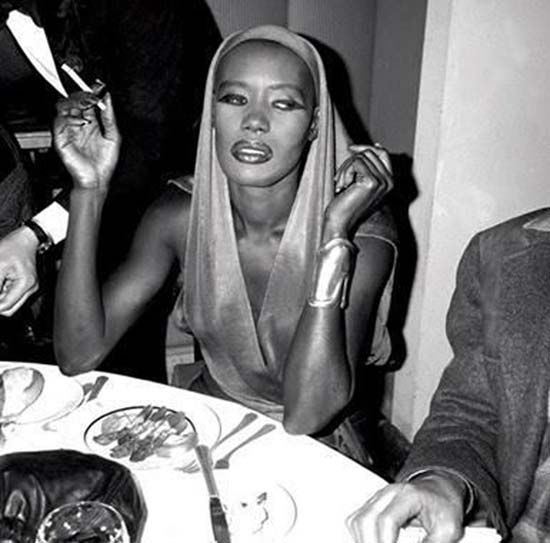

The recent passing of Elsa Peretti, the iconic jewelry designer of Tiffany & Co. who had a tumultuous life, brought back memories of the wild disco days of the late ’70s when Peretti was at the height of her fame, partying at the decadent Studio 54 with the beau monde. Many would be wearing her sculptural pieces in sterling silver, which she elevated to luxury status, or her “Diamonds by the Yard” chains, in which gave the venerable gemstone a youthful, swinging reboot.

The first time we actually saw a Peretti piece was on the neck of the late Chona Kasten, who was the modern, sophisticated and independent woman that Peretti would design for — one who would buy her own jewelry instead of waiting for men to give them as gifts.

Running counter to the flashy “trophy” jewels of the time, Peretti‘s bold, pure forms were organically sensual — art objects in themselves that had to be touched to be appreciated.

Chona’s bean pendant was one such piece, with undulating curves that practically pulsated with the origins of life itself. Worn with a simple shift dress, it would take her from her day job as consultant at Rustan’s (where Tiffany’s opened its first boutique in the Philippines) to cocktails and dancing at Coco Banana in Malate. Never to be caught dead overdressed, Peretti jewelry suited her relaxed, easy style, which the Tiffany designer epitomized.

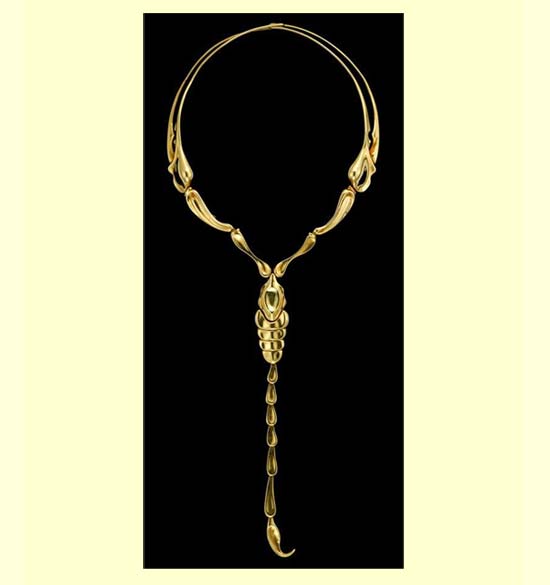

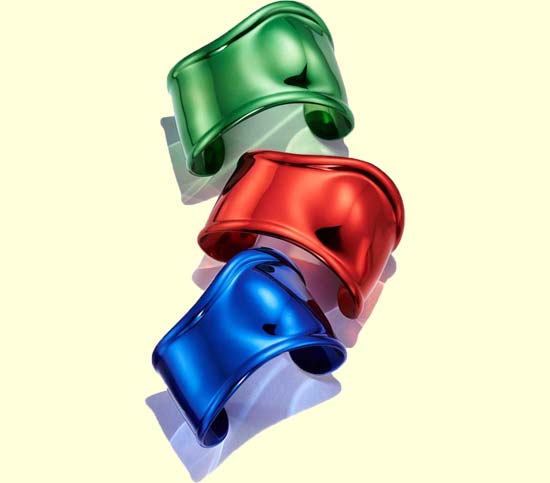

Born in Florence in 1940, Peretti had a privileged upbringing. Her mother, Maria Luisa Pighini, hailed from a noble Roman family that frowned on her marriage to the businessman Ferdinando Peretti, who later became an oil and gas tycoon. Elsa was headstrong even as a child, repeatedly bringing home bones from the Capuchin crypt despite her mother’s scoldings. The look and feel of the specimens would inspire the Bone Cuff, among other Tiffany creations.

Educated in Rome and Switzerland, the rebel daughter decided at age 21 to run away from home to be independent from her conservative family and “find a new approach to life.” She was dragged back home by her mother but left again two years later as a runaway bride, leaving her wedding dress unworn and her Italian publisher fiancé and invited guests waiting at the altar.

Cut off financially, she taught languages at her old Swiss boarding school and skiing at the posh resort town of Gstaad. Later she got an interior design degree in Rome and worked for an architect in Milan.

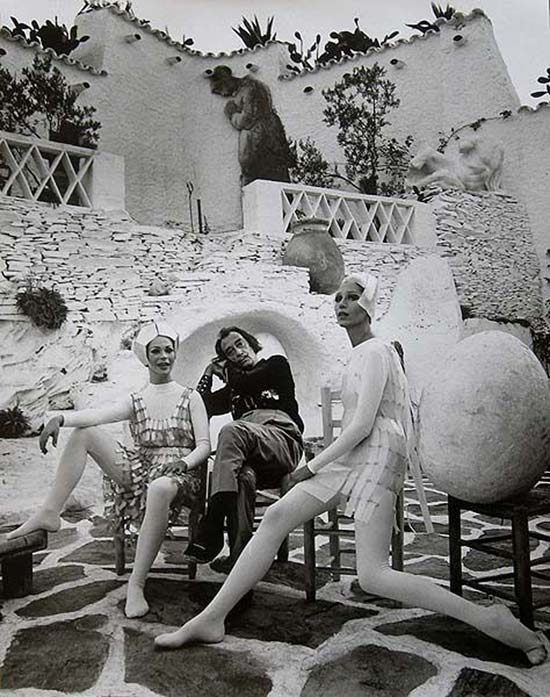

At 5’9” tall, with a slim physique and striking looks, she made the perfect model, a job she decided to try when she moved to Barcelona in 1966. This made her even more estranged from her parents, who considered the work of a model just as immoral as being a prostitute. The Catalan city would be instrumental in shaping her aesthetics as she circulated with a community of artists like the surrealist Salvador Dali. She also studied the visceral architecture of Antoni Gaudí.

A move to New York in 1968 to model with the Wilhelmina agency would be the turning point in her career, although her first day in New York might not have been as auspicious: She arrived with a black eye from her boyfriend, who was against her making the trip. She could not start work right away and hid in her hotel for days, but eventually got settled and became the favorite of fashion designers like Charles James and Issey Miyake.

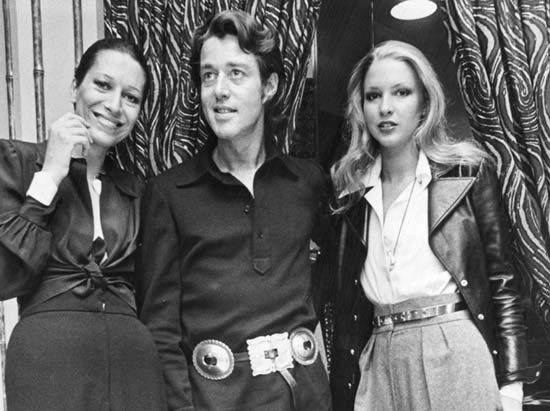

But it was her friendship with Giorgio di Sant’ Angelo and Halston that would change her life. She had already started dabbling in jewelry in Spain, where she met artisans who would craft pieces for her personal use. These would catch the attention of her designer friends who commissioned pieces for their shows, becoming instant hits.

Her sterling bud vase pendant, inspired by women of Portofino in the ’60s who would keep flowers fresh in tiny vases hung round their necks, was introduced by Sant’Angelo in a 1969 show matched with flower-child peasant looks.

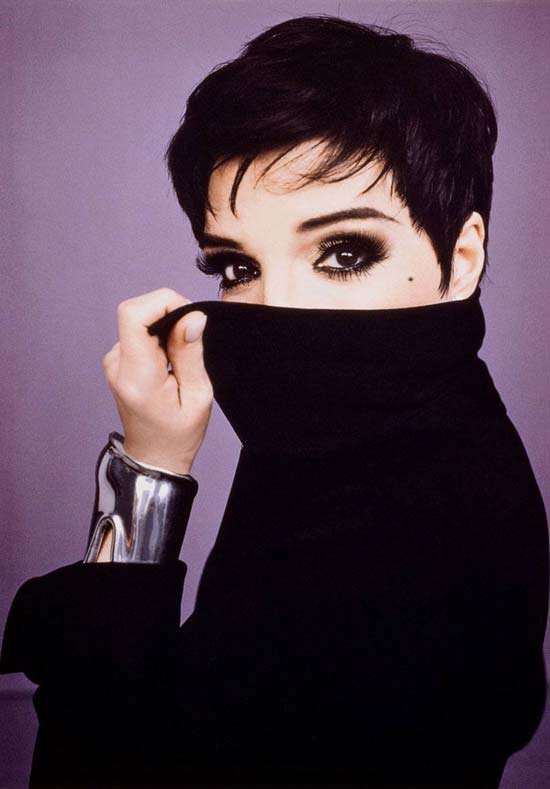

By 1971, she started designing jewelry for Halston, sticking to silver, which was quite unusual for fine jewelry at that time. Silver was considered “common” and a flea-market item, but Peretti changed the perception of the metal through her fine, evocative pieces that women would find irresistible. They actually became hip, perfectly in tune with the zeitgeist that favored the minimal, body-conscious style epitomized by Halston’s jersey and Ultrasuede sheaths worn by the Ultrasuaves, the nickname for trendsetting women like actress Liza Minnelli, art collector Ethel Scull and Vogue editor Grace Mirabella.

Just as the elite went gaga over Peretti’s jewelry, working women also desired her pieces. It was one reason why Peretti used silver — to make her line more affordable, as well as to fit the day-to-night lifestyle of this new breed.

Her work was so acclaimed that she was honored with a Coty American Fashion Critics Award for jewelry in 1971 and by 1972, Bloomingdale’s opened a dedicated Peretti boutique.

In 1974, upon the introduction of Halston, she met Walter Hoving, the chairman of Tiffany & Co., who only had to see a coral bud vase and a silver cuff bracelet for him to award her a five-year contract. “It was the right idea at the right time,” Hoving said then, noting that it was promising for their business, which had not sold silver jewelry for 25 years.

True enough, Peretti’s jewelry sold out and the designer became the subject of numerous features in the media, including a glowing Newsweek cover story in 1977 claiming that her designs started the biggest revolution in jewelry since the Renaissance. It was an article that would even catch the attention of her estranged father, who had it translated to Italian and may have played a part in their reconciliation before he died.

What also reunited her with the family was her move back to Europe. After all the decadent nights at the clubs and dinner parties, things came to a head one evening at Halston’s town house in January 1978 with fashion illustrator Joe Eula, who described the occasion as “a simple dinner of caviar, baked potato and cocaine.”

With tensions between Peretti and Halston already brewing for some time, an argument put an abrupt end to the dinner, with the former yelling, “F**k you,” as she flung to the fireplace the sable coat that the latter had given her as payment for designing the Halston perfume bottle.

After not talking to each other for three months, they bumped into each other at Studio 54, where Halston was seated with the proprietor Steve Rubell, who asked Peretti to join them and “have another vodka, honey pie,” a remark that did not translate well for the Italian designer, who snapped back, “How dare you call me that?” and would not be appeased even after the American term of affection was explained to her.

Finally, Halston declared, “This is the reason I don’t want to see you,” commencing another yelling match that ended with Peretti emptying a bottle of vodka on his shoes and smashing the bottle, to everyone’s horror.

Although she was still welcome at the club after that — proof of her cachet as well as the publicity it generated — she eventually decided to leave New York. She had bought a medieval house in the Catalan village of Sant Martí Vell, which she was slowly restoring through the years and this became her spiritual home with her beloved artisans nearby. “I go to Spain to think, I come to New York to act,” she would say, as she kept shuttling between the two countries as designer for Tiffany.

She would create some of her finest pieces in the coming decades, including an “Objects for the Home” collection, working with artisans in Japan for 70-step urushi lacquer, Hong Kong for rock crystal carving and Venice for glass blowing.

After almost 50 years, her pieces at Tiffany are still selling, having passed the test of time. Based on the company’s 2019 figures, one Peretti jewel or object is sold somewhere in the world every minute, and one Open Heart piece every three minutes. The universal appeal of her pieces have also made them 20th-century design icons that are now included in the permanent collections of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and London’s British Museum.

But money and fame were always secondary to her. “I didn’t want to become someone,” she said in an interview with WSJ magazine last year. “I wanted to do what I wanted, work with artisans, with my people. They bring my fantasies to life.”

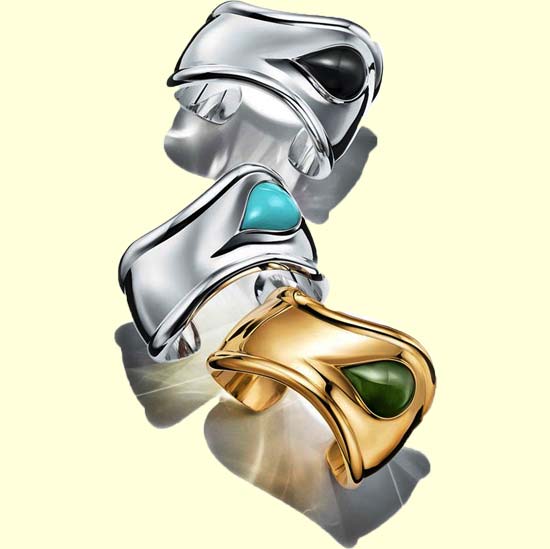

And although she still managed to update her famous 50-year-old Bone Cuff with bright-colored metallic and carved stone versions last year, and was enjoying Instagram where she has a page, a lot of her energy, not to mention her family inheritance, had actually gone to her advocacies through the Nando and Elsa Peretti Foundation set up in 2000 in honor of her father, engaging in biodiversity conservation, human rights, education, health, medical research, arts and culture, and even committing about $950,000 to COVID-19 emergency relief to help the most vulnerable, from migrants in Italy to communities in Afghanistan and Bolivia.

As she died quietly in her sleep last March 18, little did she know that she was “someone” that many would mourn, from the artisans and fans in the design world to all the people she had helped and whose lives she had touched, as seen in all the tributes on traditional and social media. And reuniting with her father whose approval she always craved, he would most certainly greet her with a resounding “Brava, Elsa!” for a life well lived.

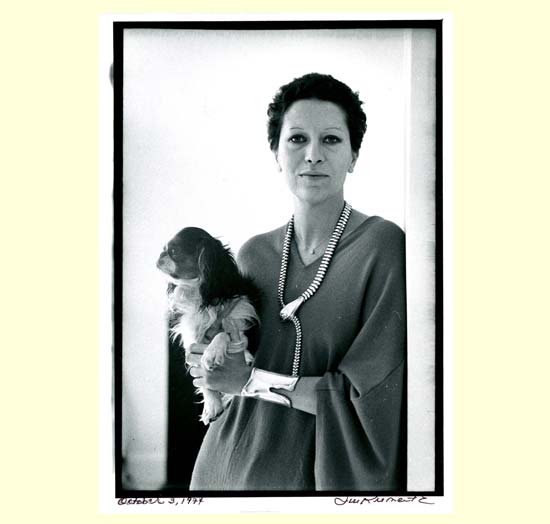

Banner photo: Elsa Peretti at work in New York, wearing her “Diamonds by the Yard” necklaces (Duane Michals/Vogue, Dec. 1974)