The hourglass always has its time

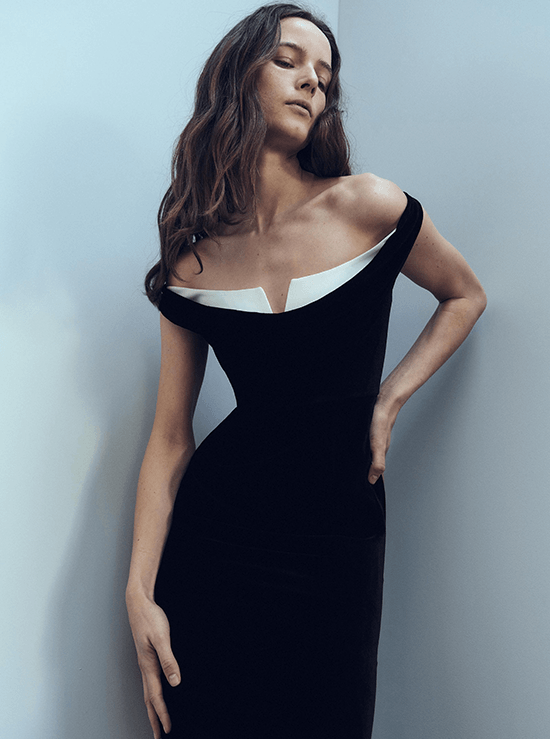

Could it be the Barbie effect? Why is the hourglass back again, as seen on the Fashion Week 2023 runways?

Named after the glass device to measure the passage of time, it’s an idealized shape of the female figure with a wide bust, a narrow waist and wide hips, with a similar measurement as the first.

It’s idealized because when one considers individual beliefs on what is best for physical health and what is preferred aesthetically, there could be no universally acknowledged ideal female body shape.

Cultural norms have developed, however, and continue to influence how a woman relates to her own body as well as how others may perceive and treat her.

The fashion industry has actually categorized three other body shapes: rectangular, where the waist is less than nine inches smaller than the hips and bust; the inverted triangle with shoulders broader than the hips; and the spoon with hips wider than the bust.

A study of the shapes of over 6,000 women carried out by researchers at the North Carolina State University in 2005 found that 46% were rectangular, just over 20% were spoon, 14% inverted triangle, and only 8% were hourglass.

No surprise then that the Barbie doll was getting so much flak for representing a minority that most women had to emulate, causing mental and physical health issues.

Different body ideals have emerged through history with the adoption of various beauty tools to achieve them. According to the feminist professor Camille Paglia, stone-age Venus figurines show a preference for “dramatic steatopygia” and the emphasis on protruding belly, breasts and buttocks is most probably a result of the aesthetic of being well-fed and fertile, traits that were not as easily achieved at that time.

In ancient Greece, bodies were regularly proportioned but fuller with ample bosoms, big backs and thick thighs and arms, with no emphasis on any particular part.

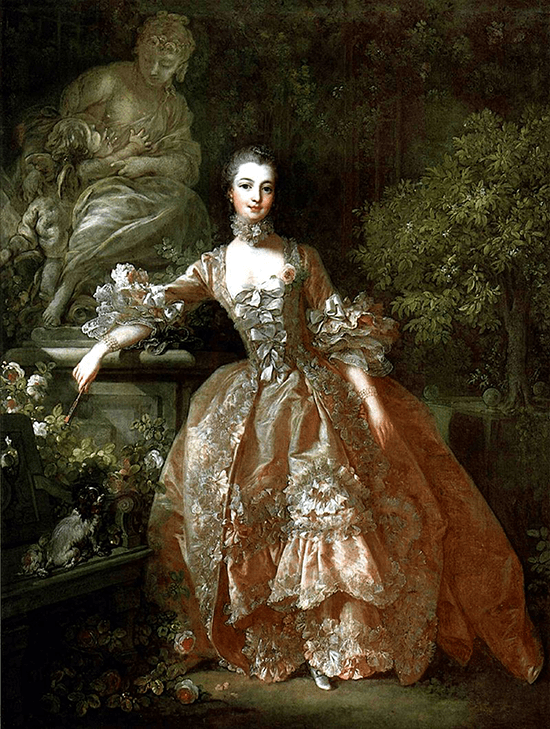

From that point, fashion somehow dictated what the proper body proportions should be since the body was seen through clothing. The first representations of fashionable women can be seen around the 14th to the 16th centuries in northern Europe when bulging bellies were desirable, although the rest of the body was thin, as can be seen in nudes as well as paintings of fashionable women wearing robes that betray the bulge underneath.

This was also true in southern Europe but because of the revival of the classics, the beauty standard reconciled the two aesthetics by using classical proportions on figures that had non-classical amounts of flesh and soft, padded skin.

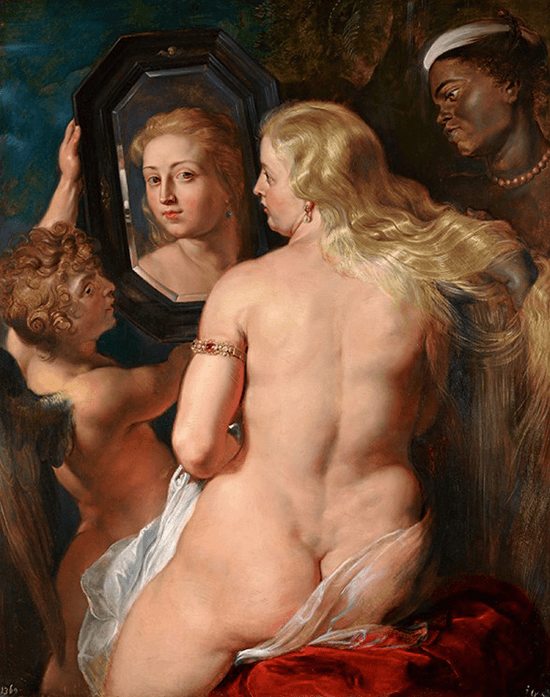

In the nudes of Rubens in the 17th century, women appeared plump but were actually of normal stature except for the flesh, with rolls and ripples that actually reflected the fashion of the day: long cylindrical gowns with rippling satin accents, tailored over a figure in stays that remained fashionable till the 18th century but were shortened, more conical, began to emphasize the waist and lifted the breasts.

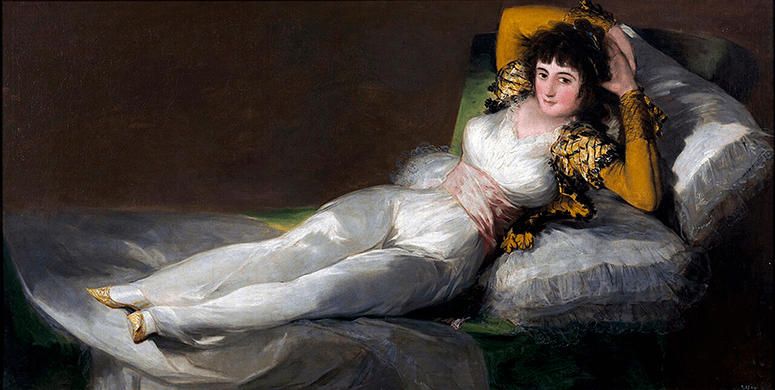

Thus, nudes in the 18th century like “La Maja Desnuda” by Goya have a narrow waist and high, distinct breasts, as if they were wearing an invisible corset.

The 19th century maintained the general figure of the last one, as depicted in works of contemporary artists like Ingres, Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec.

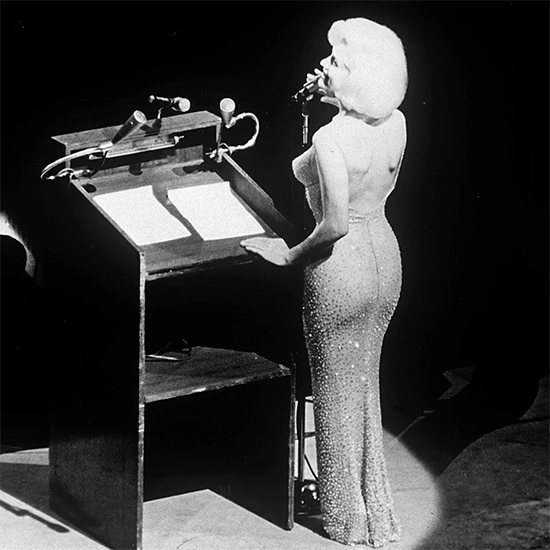

With the rise of athletics and a more active lifestyle at the start of the 20th century, the female figure slimmed drastically. By the 1920s, a boyish figure took hold, with the flapper look downplaying the chest and curves hidden behind clothing but in 1947, Dior’s New Look brought the hourglass back, which other designers like Balenciaga also adopted and exported to Hollywood where accentuated curves, big breasts and the slimmest waist were epitomized by actresses like Marilyn Monroe.

In the 1960s, it was back to a thin, petite figure, only to be superseded by the 1980s when supermodel-curvy and sporty looks were in, as well as those with broad, padded shoulders that emulated men’s power looks.

In the ’90s, heroin chic and the waif were frail and androgynous looks like that of Kate Moss.

In the 2000s, the beauty standard of the hourglass figure is at an all-time high with an unprecedented spike in plastic surgery to achieve it.

Contemporary designers have reimagined the hourglass from their house’s archives. Demna Gvasalia at Balenciaga balances reverence for the founder of the house with profane irreverence like turning the gray tweed suit into a squarish skirt split to the hip and the jacket with exaggerated shoulders pitched slightly forward and a nipped-in waist that inflates out over high, padded hips. He even pays tribute to the shape for accessories through the Hourglass Hinge Bag.

At Versace, Gigi Hadid came out with the Hollywood Hills as backdrop wearing a skirt suit that was molded to mimic the proportions of Sophia Loren in the ’50s.

At Max Mara, Alaïa and Schiaparelli, chunky belts cinched the waists while at Louis Vuitton and Chanel, wide shoulders were offset with neat, tailored waists and skinny belts.

With these styles catering to the minority who have the hourglass figure, what happens, then, to those with other body types? Surprisingly, even plus-size brands have the coveted hourglass shapes in their collections with models that pad their bodies or use corsets to imitate the coveted shape. Is this because research indicates that men prefer women with the hourglass figure?

Studies found that this shape was found even more desirable than breast size or facial features. Although they were initially drawn to the cleavage, it was the hips and waist that they found most attractive.

In any case, women today don’t necessarily dress for the male gaze and even if they do, it’s all about expressing individuality and feeling good about their choices.