The American vs. French battle that changed fashion

One of the most exciting segments of the current Halston miniseries on Netflix is the “Battle of Versailles.”

What could be more riveting than the first-ever faceoff of American and French designers at the opulent French palace of excess epitomized by Marie Antoinette, the fashionable last queen of France before the French revolution? Whose heads would face the guillotine of public opinion in this historic event that took place on November 28, 1973?

True to his diva character, Halston was being difficult about the whole project from the start, playing hard to get with Eleanor Lambert, the legendary fashion PR doyenne who created New York Fashion Week, the Met Gala and the International Best Dressed List, among many accomplishments in a stellar 75-year career.

Her meeting Palace of Versailles curator Gerald Van der Kemp, who was seeking fundraising opportunities for the palace’s renovations, would result in the pioneering fashion show that would become a coup for the American designers, whom she always believed had a right to be recognized internationally.

France, after all, ruled the fashion world at that time. American companies, in fact, would pay a fee to copy French designs and reproduce them. So being on the same stage as Yves Saint Laurent, Pierre Cardin, Emmanuel Ungaro, Hubert de Givenchy and Marc Bohan of Dior was a dream come true for American designers.

When Halston finally relented, he joined Anne Klein, Stephen Burrows, Bill Blass and Oscar de la Renta to represent the US.

The palace was not the ideal venue for rehearsals. Cold and damp, the Americans were freezing as they prepared in the evenings after the French, who had the morning shift, left the premises. Anne Klein, the only female designer – accompanied by her assistant, a then 25-year-old Donna Karan – was relegated to the even more miserable basement quarters.

More problems cropped up: the set design coordination was lost in translation, with the designer measuring in inches what should have been in centimeters.

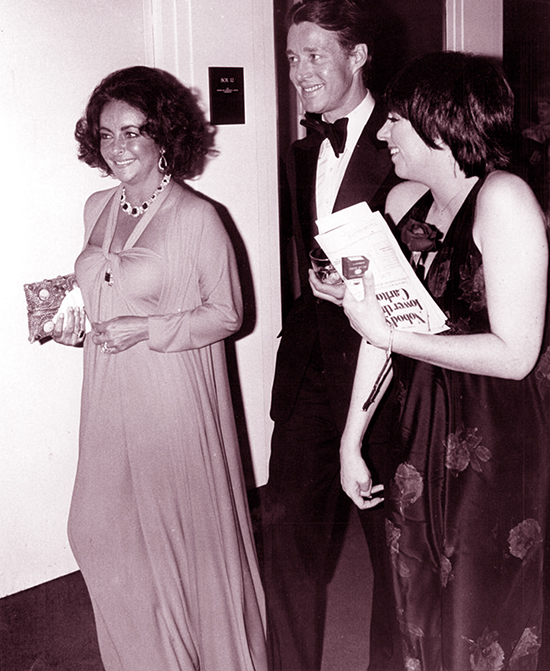

And of course, Halston was acting up again, insisting that he should be the finale and fighting with the choreographer Kay Thompson. His tantrum had both of them walking out and Halston threatening to withdraw from the show. It was only his BFF Liza Minnelli’s intercession that would patch things up and save the day.

Harassed with their preparations, the magnitude of the event only struck them on the evening of the show when the palace glowed under a full moon and a fairytale dusting of snow, as red-uniformed, saber-wielding gendarmes flanked the gilded gates, together with 100 footmen in 18th-century white powdered wigs and livery.

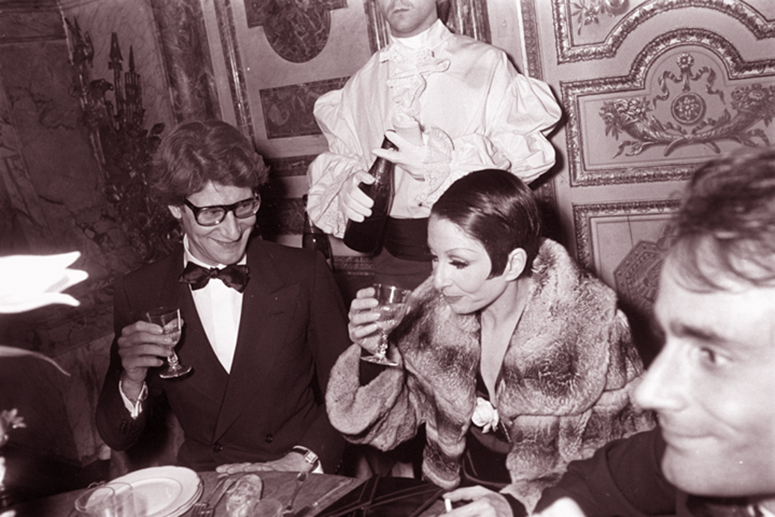

The queen of the night was the evening’s host, Marie-Hélène de Rothschild, scintillating in a green ostrich-trimmed gown by Saint Laurent and solitary diamonds sparkling from her hair as she greeted the beau monde, from Grace Kelly, the Princess of Monaco, and the Duchess of Windsor, to Jacqueline de Ribes and Gloria Guinness.

Flying in from America were Andy Warhol and the Texas socialite Lynn Wyatt, who found the whole affair overwhelmingly jaw-dropping: “The hype of the thing was enough to make your eyeballs go up into your head. You opened your eyes and you were just blinded by the splendor and beauty.”

Absent that evening was Raquel Welch, who was disinvited because Liza Minnelli threatened not to perform if she attended.

The American designers, walking to their private boxes at the palace’s Théâtre Gabriele, “felt like entering the Colosseum to be devoured by the lions,” according to Robin Givhan in her book, Battle of Versailles. For the mostly French audience of 700, this was really just a sport to display French superiority and see how far the Americans could go and what amusement they could provide for the evening.

True enough, the presentation of the French just went overboard to display their Old-World cultural advantage over the younger nation, with full orchestras, elaborate 17th-century sets (“So tacky they weren’t even camp,” reported Fairchild in WWD), dancers from the Crazy Horse cabaret, the ballet star Rudolf Nureyev, and the musical icon Josephine Baker.

There were even live rhinoceroses, one of them pulling a gypsy cart in Ungaro’s segment, a rocket ship for Cardin, a pumpkin-shaped carriage for Bohan, and a “mile-long” Bugatti for Saint Laurent.

The emphasis was the spectacle and the resources that they had, more than the clothes, which had all the hallmarks of haute couture, from Lesage beading to sprays of feathers and other rich fabrications.

In contrast, the Americans went minimal – with only a last-minute sketch of the Eiffel Tower by Joe Eula as a backdrop and prerecorded music (on a cassette!) blaring from the speakers. Liza Minnelli pep-talked the 36 models to a spirited opening number of Bonjour, Paris with all the exuberance of a hit Broadway musical.

The star had instructed them, “You’re not modeling, you’re acting — just like people seeing the Eiffel Tower for the first time. The more natural, the better.”

They were a refreshing sight, all in beige quintessential sportswear from the five designers. It was the liberated spirit of America that was so infectious and revitalizing in that old, dusty symbol of the Ancien Régime.

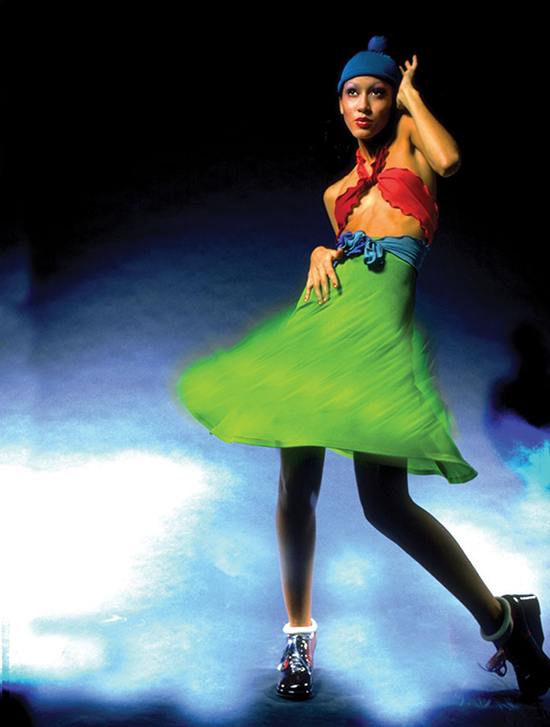

What was even more astounding and tradition-breaking was the fact that 11 of the models were African-Americans, something unheard of at that time. And how those models moved, each with her own interpretation of the music and what she was wearing.

They now actually had their own personalities as opposed to the “mannequins” of Paris, who walked in a slow, self-conscious way with hands-on hips or like robots holding number cards at the salons.

The speed of modeling and change of garments was also NY-metropolis fast, made possible by clothes designed for quick-moving, independent women — no zippers or hooks that encumbered their elaborate French counterparts.

Anne Klein’s “Africa” collection of pleated skirts, djellabas, shirtdresses and two-piece dresses with coordinating turbans got the show off to a rousing start.

Burrows came next with wildly colorful, body-conscious matte-jersey gowns, many color-blocked halters with rippling hems that gave a sensual energy. Inspired by NY underground downtown clubs, he encouraged his models “to really have fun and cut loose on stage.”

His finale was a long-trained dress worn by Pat Cleveland, who came out spinning nonstop till she reached the edge of the stage with a perfect landing that had everyone sigh in relief. Then the rest of the models who were at the back all rushed en masse up front to join her. Upon reaching the edge, they froze and started posing — it was the precursor to Madonna’s “vogueing.”

From downtown, Bill Blass brought the proceedings uptown with his Jazz Age retro glamour of daytime suiting, dazzling sequined slim skirts with tailored jackets and jersey mixed with sable, all with the café society sophistication that the designer was famous for.

Then came Halston’s segment heralding evening wear worn by his famous friends and models, who were dramatically positioned frozen in pitch darkness with the spotlight landing one by one on each of them to suddenly animate them to life. The clothes were all done in his signature sensual elegance with luxurious fabrics and cut for easy movement.

For the finale, De la Renta used Barry White’s lush Love’s Theme and cast Billie Blair as a seductive magician in a diaphanous chiffon caftan, pulling out swathes of fabrics in colors that signaled each suite of ethereal gowns. As the music swelled to a climax that ended the show, the audience were up on their feet clapping and programs were thrown up in the air.

It was an obvious triumph for the Americans, who were dumbfounded. The French designers complimented their counterparts generously. Although for them, the clothes were not really “feats of technical wizardry, the magic was how the presentation connected the clothes to contemporary life, shown with personality, movement and individuality,” observes Givhan.

It really paved the way for a more modern approach to fashion and the popularity of pret-a-porter, not to mention that it put American design on the world map, making New York Fashion Week a must on the calendar.

American designers also gained respect on the world stage, making it possible for people like Tom Ford, Marc Jacobs and Alexander Wang to be appointed as creative directors for European houses. Diversity also got a jumpstart, with models of color making it to the European runways. Ultimately, it wasn’t that the Americans or the French won, but that it was a huge triumph for fashion that evening.