What female rage in movies can teach us

More often than not, when I feel my anger, shame will immediately replace it. My first instinct is to invalidate myself, to question if what I feel is wrong.

My anger is unnatural.

My anger is unbecoming.

So I learned how to rein myself in. In situations where I felt such blinding anger because of how I, or the women around me, were treated, I chose to placate and tiptoe. I chose to make light of my own emotions.

I didn’t want to cause a scene or be labeled as a hysterical, crazy woman.

“Almost every woman I have ever met has a secret belief that she is just on the edge of madness, that there is some deep, crazy part within her, that she must be on guard constantly against ‘losing control’—of her temper, of her appetite, of her sexuality, of her feelings, of her ambition, of her secret fantasies, of her mind.”—Elana Dykewomon, “Sinister Wisdom 36: Surviving Psychiatric Assault & Creating Emotional Well-Being in Our Communities.”

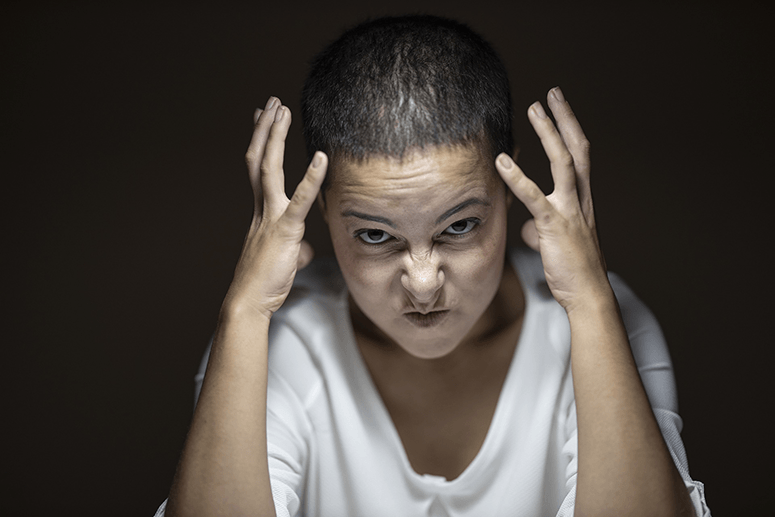

Recently, there’s been a rise in films depicting female rage. TikTok edits will show you compilations of fictional women screaming their lungs out, their anger so primal and raw—not glamorous and glittery and “cute,” the way Hollywood has conveyed women’s emotions for so long. Of course most of these actresses are still conventionally beautiful, but the anger they portray is far from it. It is ugly and loud, and it takes up space.

@isabellarlash Acting Anger- Part 2 ? #actingemotions #actingemotional #actingemotionschallenge #actors #actinginspo #actorskills #actingstudent #actingtiktok #act ♬ original sound - Isabella Lash

“Female rage” films turn the angry woman trope on its head. Instead of a nagging wife or an unbearable boss, the characters in these films are horror villains and antiheroes. In Pearl (2022), Mia Goth plays the titular character who gradually loses her mind; resentful of her current circumstances, she lashes out and goes on a murder spree. Similarly, Carey Mulligan’s Cassie in Promising Young Woman (2020) goes on a revenge tour, retaliating against everyone who hurt her best friend.

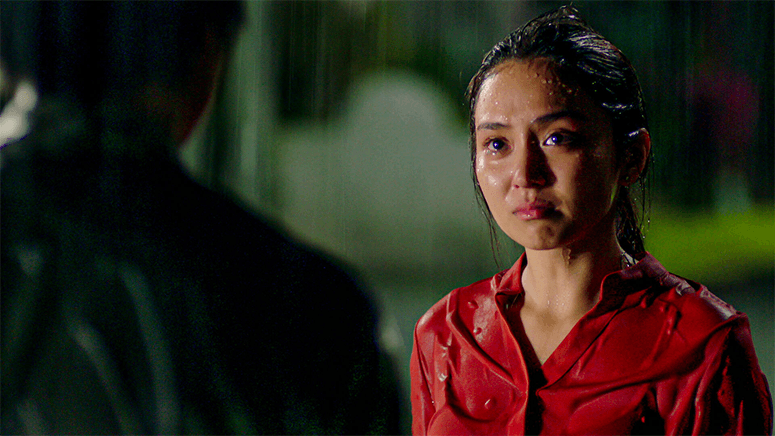

There are other depictions of female anger, however, that don’t necessarily center on homicide. A scene from Hidden Figures (2016) has Taraji P. Henson’s Katherine yell out her frustrations about having to use a segregated bathroom far away from her office. Hereditary (2018) has Toni Collette’s Annie explode at her son, letting out her grief and anguish from losing a family member. A quiet yet realistic form of female rage is portrayed by Katherine Bernardo in The Hows of Us (2018): she allows the emotions that she’s suppressed to come to the surface, expressing how fed up and tired she is of having to sacrifice so much for her partner.

“It took me too long to realize that the people most inclined to say, ‘You sound angry’ are the same people who uniformly don’t care to ask, ‘Why?’ They’re interested in silence, not dialogue.”—Soraya Chemaly, “Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women's Anger”

What draws us to these films? Catharsis and satisfaction.

It was frustrating to always see women onscreen just shedding a lone tear when they got mad. I wanted to scream too, to let out what was pent up inside me. We’ve seen endless amounts of men’s anger; when a woman is portrayed with the same emotions, in real life or onscreen, they’re treated as a joke at best. At worst, they get sexualized—see the femme fatale trope with characters like Catwoman or the James Bond girls.

So in a world where I am told to calm down, where my tears and the volume of my voice take precedence over what I am saying, female rage in media feels therapeutic.

These characters live in a world where their feelings are taken seriously. It’s satisfying because their anger, while fictional, is often a response to real systematic oppression. In reality, acknowledging such underlying injustices can be difficult.

In reality, speaking out could do a victim more harm. Getting angry could attract unnecessary attention or diminish the importance of the cause you’re fighting for. Standing up for yourself, expressing dissent, or just talking about how mad you are could get a violent response.

To the women reading, ask yourself how many other women you know have stories of getting sexually assaulted. How many have received inappropriate comments, or have suffered from misogynistic micro-aggressions? How many have tried to open up about these experiences, only to get harassed by people who don’t believe them?

There are some things that we should definitely be angry about, and if we use this feeling the right way instead of pushing it down and letting it poison our insides, then maybe we can unlearn shame. It’s up to the rest of the world now to learn how to take us seriously.

In The Invisible Man (2020), the protagonist played by Elizabeth Moss is put into further danger when the people around her refuse to believe that her abusive ex is still stalking her. This is a terrifying parallel to how some stalking cases in real life are not given proper attention until it’s too late. Last year, for instance, a woman from South Korea was killed by her stalker even after she reported his alarming behavior to the police.

The #MeToo movement also had its share of backlash, especially about how women were overreacting to “minor” transgressions. It seems people had more empathy for the “innocent” men with accusations rather than their victims.

Who wouldn’t be angry?

But being an angry woman means being an irrational woman. You can’t be reasoned with and your feelings are clouding your ability to think straight. To be taken seriously, you need to be calm and collected. Being emotional will only work against you.

Seeing unbridled female rage in films lets me explore my own emotions and allows me to validate them. I understand now that my anger is the part of me that loves me, that lets me know when I’m being mistreated. It’s a measure of how much I care about myself.

“Jiyoung became different people from time to time. Some of them were living, others were dead, all of them women she knew. No matter how you looked at it, it wasn’t a joke or a prank. Truly, flawlessly, completely, she became that person.”—Cho Nam-Joo, Kim Jiyoung, born 1982

Although it’s not to the extent of Pearl or Cassie (I, for one, am not up for killing people), I find their rage and its causes all too relatable. You can see yourself in these characters, and it feels good to see them let go and just feel things without needing to apologize.

It’s not unwomanly to get mad, after all. It’s human. I was mad, too, writing this.

I was angry about all the times I told myself I shouldn’t be, about all the times I thought more about what the reaction to my anger would be.

There are some things that we should definitely be angry about, and if we use this feeling the right way instead of pushing it down and letting it poison our insides, then maybe we can unlearn shame. It’s up to the rest of the world now to learn how to take us seriously.