Why do we keep using sex to take women down?

Nobody ever talked to me about sex, but it seemed everyone was more than game to discuss sex tapes.

I was nine when Katrina Halili and Hayden Kho were at the center of a viral sex scandal that, perhaps inevitably, made its way to my newly minted Facebook account. Usually, sexual curiosity was squashed before it piqued, but this time, I had the answers even before I knew to ask — by which I mean I was told warnings, often strongly worded, almost always gendered, against something I had yet to fully understand.

For years this didn’t change. Conversations on sex were nonexistent unless laced with shame and threat. Don’t be like the girl from high school whose nudes were leaked —remember her, and the students who sold links to the Google Drive folder for a hundred pesos? And the ex-boyfriend who was supposedly the sole recipient of the photos in the first place; which one was he again?

Frustratingly, the gossip mill’s vitriol was rarely extended to my male peers. The very premise of sharing private, sexual photos and videos without a person’s consent for the sake of humiliation — aptly called “revenge porn” — is built on such sexual double standards after all. Ones that tolerate, even expect, robust male sexuality while simultaneously constructing women as sexualized but not sexual. And if you were the latter? ‘Di ka na nahiya, ka-babae mong tao.

This misogynistic subjugation is so chronic and so entrenched in our culture, so effective in its eroding of the selfhoods of Filipinas.

In 2016, House Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez approved the showing of Sen. Leila De Lima’s alleged sex tape during the House of Representatives’ probe into the illicit drug trade in New Bilibid Prison. In 2022, rumors of an alleged sex tape featuring Aika Robredo surfaced amidst a heated campaign period.

When Andrea Brilliantes expressed disappointment at unofficial election results, critics were quick to recall her own viral scandal despite it having no correlation at all.

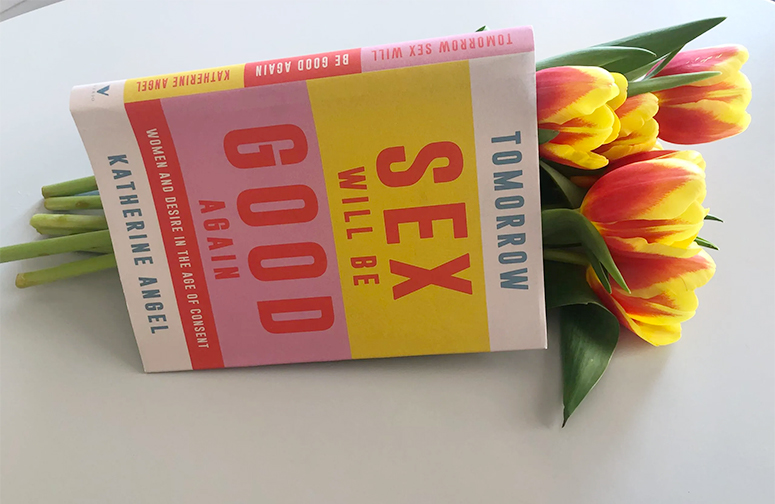

Respectability promises no immunity when the well-oiled machinery of the patriarchy continues to successfully weaponize this scarlet letter. Katherine Angel, in her book Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again, writes: “(A woman’s) desire disqualifies her from protection, and from justice. Once a woman is thought to have said yes to something, she can say no to nothing.” In the same way, once a Filipina has been made “impure” by her sexuality, with or without her consent, she is tainted and therefore powerless.

Such is the potency of taboo in a collectivist culture like the Philippines: the indecency and disgrace ascribed to a sexual(ized) woman are never hers to carry alone, but her family’s as well.

From a young age, women are taught not only to avoid sexual feelings but to see them as morally bad, as something that would embarrass their loved ones; that their feelings of sexual desire are destabilizing to the social order.

Researchers Margarita Delgado-Infante and Mira Ofreneo found in their 2014 study that Filipino adolescents defined sex as profane or bastos unless occurring within marriage, where it becomes “sacred.” Sex is always placed at an extreme, far from what it actually is — normal.

They also point out that within the context of Philippine Roman Catholicism, our sexual attitudes remain largely conservative. A good woman is a celibate one, modeled after the Blessed Virgin Mary. Premarital sex is not just bad but sinful.

At the root of these beliefs is our colonial history; it is the Spanish, after all, who introduced this virginal female ideal. Friars also took an active role in the study of the Philippines’ native languages, and the dictionaries they produced deliberately made no mention of reproductive organs.

Filipinas at the time found it all the more challenging to assert their sexuality amidst the intense social control of the colonizers; its omission from their vocabulary is akin to its erasure in reality.

As a result, many modern-day Filipinas often feel guilt and anxiety over the perceived conflict between their sexual feelings and their restrictive upbringing. They internalize the culturally derogatory view of female sexuality and police themselves and others, practically doing the patriarchy’s work for it.

After all, slut-shaming is hardly an exclusively male practice. Just last year, Nadine Lustre rightfully expressed disgust at unsolicited comments about her body; showbiz columnist Cristy Fermin consequently called out the actress for her revealing clothing, implying the body-shaming Lustre received is her fault for not covering up.

Women are often the first to criticize their fellow women — they are taught to practice sexual restraint as a protective measure against unwanted advances and attention, so if you deviate from this norm, then what do you expect?

Of course, women are not simply at the mercy of social institutions. Contrary to the presumption that they are passive sexual objects, Filipinas actively negotiate and reinterpret the beliefs they grew up with in order to fashion for themselves a sense of sexual autonomy.

Local research as far back as the early ’80s revealed a hidden youth subculture in which Filipinas have sex guilt-free; the fact that it’s invisible creates the false impression that they are sexually conservative.

I suppose this invisibility is an act of self-preservation in a culture that either demonizes or refuses to acknowledge the sexuality of half its population. Fortunately, many Filipinas today continue to resist this imposed conservatism and assert their sexual agency in their own ways, like creating online spaces to safely discuss sex or simply being more candid about what they want with their partners.

Then again, sexual autonomy shouldn’t be something individual women have to work for — it must be a given.

This comes with openly talking about not only sex but the bigger forces that continue to shape it — the patriarchy, capitalism, imperialism — forces that may sound abstract but loom much, much closer to us than we think. When we offer warnings to young girls come the next viral scandal, perhaps it’s time we point fingers at the perpetrators and the culture that has long enabled them to persist.