The lack of a divorce law affects Gen Z, too

Every week, PhilSTAR L!fe explores issues and topics from the perspectives of different age groups, encouraging healthy but meaningful conversations on why they matter. This is Generations by our Gen Z columnist Angel Martinez.

For one of the most forward-looking countries in terms of female empowerment, the Philippines falls behind in one crucial area. As of this writing, we are one of two countries in the world who refuse to grant women the right to divorce—the other, of course, being the Vatican. Effects on the wives are well-documented and have been thoroughly discussed: recurring patterns of trauma and abuse, further strained familial relations, and economic dependence on their spouses being a few.

But there’s something to be said about how this affects Gen Z and our view on love and relationships as the product of these broken families.

“The absence of a divorce law in the Philippines has had profound effects on their children, including difficulty forming healthy relationships later in life, and even an internal struggle with their sense of identity and belonging,” Cici Jueco, women’s rights advocate and lead convenor of Divorce the Philippines Now International Lobbyist (DIPI), tells PhilSTAR L!fe. “They may develop a cautious or skeptical view of marriage, in fear of repeating their parents’ experiences.”

True enough, when my conversations with friends get a little too deep, this overarching sentiment tends to surface: They don’t want to end up like their parents. “I feel like they really could have been good friends if they weren’t stuck fighting in the same house all the time,” one once told me, as she nursed a bottle of Smirnoff. “I’m just scared that I might be rushing into things like they did. If they hadn’t, maybe they could have made it work,” said another in a completely separate instance, over a cup of coffee.

So even if they’re still willing to ride out the length of a relationship, marriage no longer seems mandatory. Either they’re delaying the time it takes to get there, or contemplating if it’s even their ideal end destination at all. Gen Z no longer sees marriage as a requirement for a better existence, but a mere supplement: We can do without it, and will choose not to go into the arrangement head-on unless we’re sure we’re bringing the right person along.

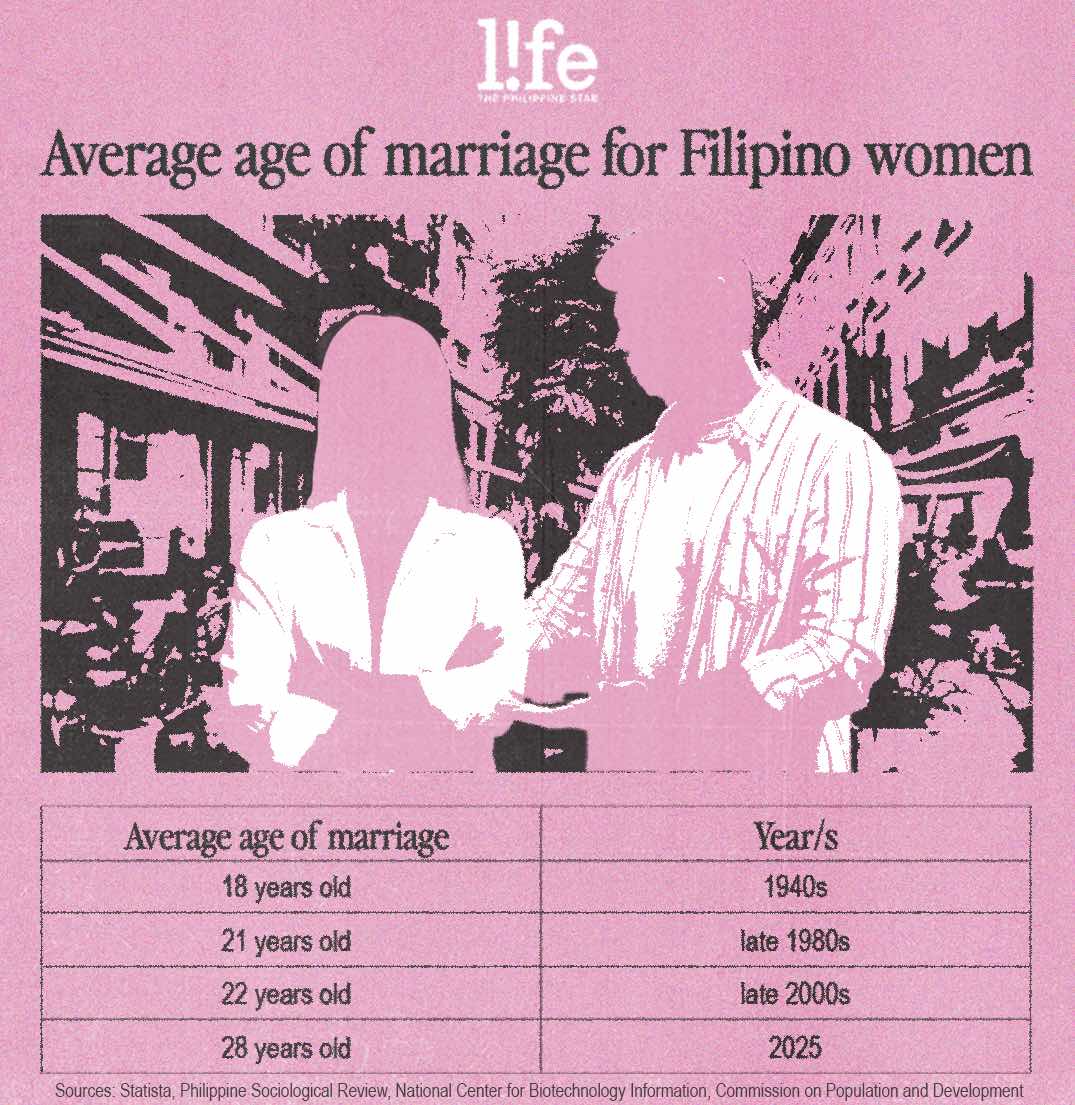

Recent trends show that Filipino women are getting married later compared to previous generations. This year, we sit at a respectable 28 years old; a stark contrast to 18 in the 1940s, 21 in the late 1980s, and 22 in the late 2000s. Cohabitation has also emerged as an alternative, with the percentage of couples living together out of wedlock soaring from 5% in 1993 and 18% in 2017.

While financial capacity and increased career opportunities for women definitely factor into this, there’s a noticeable shift in ideologies among younger demographics. “Many young adults, having witnessed the struggles of their parents in unhappy marriages, opt for cohabitation as it’s perceived to be less binding and easier to exit,” Jueco says. A recently published study of the Commission on Population and Development affirms that cohabitation grants young couples the freedom to start a family without the influence of societal pressures, as well as the opportunity to get to know each other before possibly jumping into a bigger commitment.

I can already predict the pushback from more conservative readers, and honestly, I get it. The institution of marriage was once unanimously seen as sacred, a testament to a couple’s commitment to the life they will build together. But the risks and costs of entering a partnership with the wrong person are growing far too large to ignore: The declaration of nullity of marriage can take anywhere between 10 months to several years, depending on the complexity of the case, and cost around P150,000 to P300,000 sans lawyer’s fees. Until more affordable alternatives are made available, I don’t think Gen Z can be blamed for having one foot out the door.

he Philippine Legislators’ Committee on Population and Development previously noted key differences between absolute divorce and annulment.

In terms of expenses, spouses whose properties are below P2.5 million are exempted from several fees. Those who seek annulment would have to pay for legal, psychological, and other fees, which would range from P150,000 to P300,000.

Unfortunately, we’re not exactly sure when that’s going to happen: “Divorce has always been a sensitive issue in the political and cultural landscape, with proposals for its legalization facing strong opposition from conservative hypocrites, misogynists, and bible trumpeters’ groups,” Jueco laments. “There’s also this idealization of marriage, this prioritization of family preservation over women’s autonomy in abusive or irreparable marriages.” Those still confined within these mindsets are still the main decision-makers so it may take a while before we see any progress on this front.

During situations like this, Gen Z can feel particularly helpless: What can we do to speed up the process? What is there to do but sit and wait?

Fortunately, not all hope is lost. Last May 2024, a bill reinstituting absolute divorce in the country was approved by the House of Representatives on the third and final reading and transmitted to the Senate. Another version of the consolidated measure was passed by the Senate Committee on Women, Children, Family Relations, and Gender Equality in 2023 and is awaiting a second reading. As we patiently await some progress, Jueco pushes for stronger institutional reforms for more emboldened women: “This could be through implementing strong measures against violence, integrating gender senstivity into curricula, providing more accessible shelters or counseling services, and just fostering a culture of protection and respect for women and children,” she suggests.

By empowering girls early on, there’s a higher chance of strengthening our sense of self. We grow confident that we can live without marriage, and that should we choose to partake in it, we deserve the right to walk away.

Generations by Angel Martinez appears weekly at PhilSTAR L!fe.