F. Sionil Jose: ‘I am trying to show how the nation can redeem itself, how the Filipinos can have a nobler image of themselves’

It is not uncommon for those of humble beginnings to champion the cause of social justice. Yet rare are those who speak their truth tirelessly and without compromise.

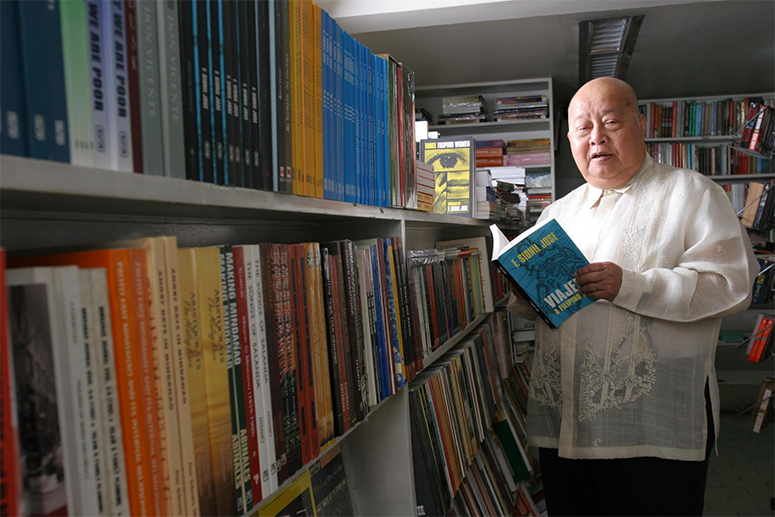

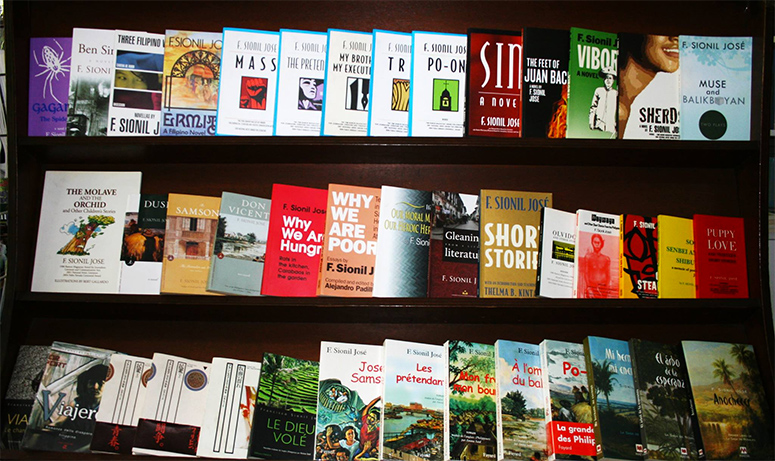

National Artist of the Philippines F. Sionil Jose is among this exceptional breed of people. The multi-awarded and prolific writer has been the recipient of the highest honors in the fields of the arts and letters, including The Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature and Creative Communication Arts in 1980, the French government decoration of Chevalier dans L'Ordre des Arts et Lettres in 2000, and the Japanese decoration Kun Santo Zuibo Sho (Order of the Sacred Treasure) in 2001.

On the exodus of Filipino talents abroad, which Sionil referred to as ‘brain hemorrhage’: ‘We are the proletariat of the world. This is our shame and pride.’

In 2004, he was awarded the Pablo Neruda Centennial Medal of Honor, a distinction he shares with 100 writers from 65 countries. His novels have been translated into 28 languages, making him perhaps the best exponent of Filipino life and culture.

While most Filipinos have come to accept the failures and fit starts of their political system as a matter of course, Jose harps on well-worn themes that have become a part of the Filipino experience — the corruption of the leadership, the lethargy of the establishment, and the capacity of common men to overcome.

Now in his 80s, he holds on to the hopeful prospects of the nation and the people as he has done throughout his life. Underlying this belief is an abiding faith in his countrymen, bolstered by their revolutionary traditions and their heroic struggle to forge a nation. In the lecture titled "The Writer as Historian,'' Jose expounds on these heroic virtues.

"Ask the Spaniards — we may have been the last of the Spanish colonies to free ourselves of them, but we were the first in Asia to mount a revolutionary war. Ask the Americans who, like us, have very short memories. They forgot the ferocity of our resistance in the Philippine-American war. If they remembered, they would have never ventured into Vietnam for it is in the Philippines that they first faced the intractable force of Asian nationalism. Ask the Japanese... it was here in the Philippines where they faced the most heroic defense of the Filipino homeland."

Despite the strong words, there are times when this staunch faith in his fellowmen is put to a test, times when the man must wrestle with his long-cherished views and the realities on the ground.

Speaking on behalf of the common man comes naturally to Jose. The son of landless peasant farmers from the llocos region was no stranger to the social injustice that those of his lot came to know and to endure. Jose grew up with an inquiring mind and an abiding curiosity that was fueled by literature.

In the public market of his hometown in Rosales, Pangasinan, great classics of literature were translated into llocano and sold alongside salted fish and vegetables. Jose devoured the writings of literary giants and life beyond the village of Cabugawan opened before him. Soon, hard questions begged for answers.

The aspiration for a brighter day led him to the city where at least part of those answers would unfold. Half a century had gone by in which time he had built a satisfying marriage and family life, a career that earned him heaps of praise and his share of controversy, and yet the same question continued to crop up — how to build a just society in light of history and present realities.

If the role of an artist is to mirror the realities of his time, then art serves to bind people to a common heritage. Yet in the most fundamental way, Jose believes that writers are essentially storytellers — heirs to the oral traditions of times past.

Frustration comes to all artists. Yet an artist must never tire of serving his muse. “The muse is the mistress that the artist must serve with everything he has and with his life if necessary,” Jose points out. The muse that Jose speaks of is the Filipino, in particular the masses, whom he sees as the real nationalists in the country — those who respect the motherland as a nurturing and sustaining force, those who sacrifice for love of country and in service of the nation.

Yet these very people, as depicted in Jose's novels, have been left behind, betrayed by a system that condones corruption and turns a blind eye to social injustice as a way of life. Speaking of nationalism, he says: "Nationalism is meaningless if it does not refer to the basic needs of a society and the basic criteria is justice. It's unjust when people can't eat three times a day, when our teachers have to go to Hong Kong to work as maids or when you get sick, and you die because you can't afford medicine. All these injustices cry for action, for redemption, for revolution."

If the role of an artist is to mirror the realities of his time, then art serves to bind people to a common heritage. Yet in the most fundamental way, Jose believes that writers are essentially storytellers — heirs to the oral traditions of times past. In his time, Jose has told many a tale; most famous among these is the "Rosales Saga." The five novels that comprise the saga span nearly a century, tracing the story of a town and its families against the backdrop of Philippine history.

The first novel of the quintet, Dusk, was named in The New York Times Book Review section as one of the 100 most notable books of 1998. Set in the 1880s, Dusk tells the story of tenant farmers who are forced to flee their native Ilocano village and start life anew in the town of Rosales.

More than just a story of the struggle and survival against social injustice in the final years of Spanish colonial rule, it tells of one man's journey to find the hero that is within. To be sure, the protagonist lstak Samson is the "uncommon" common man — the simple farmer who rises to the heroic call of duty in the Battle of Tirad Pass, the last stand of General Gregorio del Pilar and his men against the invading Texas Rangers closing in on General Emilio Aguinaldo, the first President of the Philippine republic.

If one is to believe that nothing in life happens by chance, then everything in lstak's life prepared him for this destiny. Here, as in many of Jose's novels and short stories, he tells us that the capacity for greatness and heroism lies in each of us and that such qualities reside in simple men who must rise above overwhelming odds.

I also present a nobler image of Filipinos so that even if we are destitute, amidst the swirling tides of corruption, we can raise our heads. With memory, we can face our grim future with courage.

More than three decades in the making, Dusk draws on the accounts of village elders who bore witness to the life and times of the peasantry. Of them Jose writes, "I grew up with the knowledge of their suffering in their new land, their exploitation by the landlords, the eventual dispossession of their lands. I also knew of the hardiness of their spirit, the dreams they shared and the angers that made them endure."

Memory is what Jose shares with his readers. For beneath the young nation continuing to seek her identity, her place in Asia and the world, are a people who have fought to uphold justice and freedom time and again — in 1896, in Bataan, in the People Power movements that toppled dictatorial and corrupt regimes.

Filipinos must not forget their heroic heritage, for their nation was the first in Asia to establish a democratic republic. Filipinos must not forget — especially not the heroes of the underclass who are often overlooked by historians as they focus on seminal events or larger-than-life figures, so Jose tells his readers.

In a lecture at Stanford University as a writer in residence, he remarked, "I use history to impress upon my readers this memory so that, if they remember, they will not only survive but prevail. I also present a nobler image of Filipinos so that even if we are destitute, amidst the swirling tides of corruption, we can raise our heads. With memory, we can face our grim future with courage."

Valid as his historical perspective may be, he does have his share of detractors. There are those who say he romanticizes the mundane, and those who deride his use of inelegant prose. He has been accused of Filipino-bashing, labeled a communist, a CIA agent and called an opportunist.

"In truth," he says, "I am just an old writer whose discordant voice is drowned, unheard in the maelstrom that is my country." Still there is no denying that the man has made his message abundantly clear. For international readers and reviewers alike, Jose is the one writer who brings all the aspects of the Filipino condition to light. After long years as a bitter critic of the Marcos regime, and railing against the social and political malaise that grips the nation, Jose tirelessly moves from one passion to another.

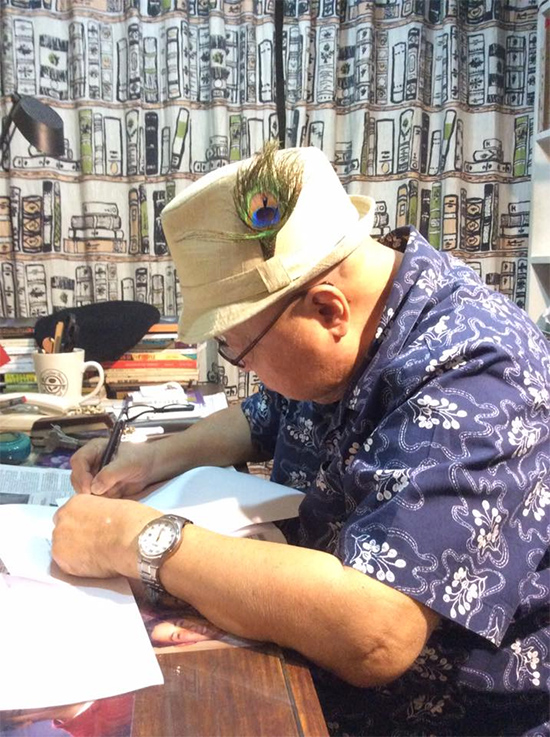

His latest obsession is a novel about Artemio Ricarte, the revolutionary general who refused to pledge allegiance to the United States at the end of the Philippine-American War in 1902. Jose has been at it for nine long years, so long that he says, “the research has been flowing out of my ears and shackling my imagination." Invariably, it raises the subject of America's long involvement in the Philippines, first as a colonial power and later as a strong and staunch ally in the Asia-Pacific region.

Like all Filipinos, Jose has ambivalent feelings about the American legacy in the Philippines. On one hand, he sees America as a benevolent power that has been a force for good in the world. Yet he is quick to acknowledge the flip side — that America committed its first atrocities in Asia when more than 250,000 Filipinos were killed during the Philippine-American War. Like the Spaniards that preceded the Americans and the Japanese that came after them, Jose grants that all had their virtues as well as their vices.

He abounds with tales of exploitation that colonialism breeds and weaves it all into his narratives. Yet for many Filipinos, America and its way of life is the embodiment of hope — where one seeks the promise of a better life and a real shot at success. Jose believes that it is more than high time to cut the umbilical cord. In intellectual circles, many share his view that Filipinos must rid themselves of the “American hangover," celebrate their distinct heritage and build solid cultural foundations before they are swept aside by the tides of globalization and McDonald's.

Much to his sadness, Filipinos today are scattered all across the globe searching for the promise of America in other parts — from Iran to Indonesia, from Singapore to Saudi Arabia, in Tokyo, in Hong Kong or in Italy.

Jose is armed with stories of Filipino talent and genius that have helped build the skyline of Singapore, or that sustain New York's healthcare system. An Indonesian businessman once told him that most of the banks and corporate headquarters in Indonesia are run by Filipino managers. A Boeing executive likewise told him that, were it not for Filipino technicians, Iran Air would not get off the ground.

As Jose points out, there is no oceangoing vessel without a Filipino aboard. Not long ago, Newsweek magazine referred to this exodus as a "brain hemorrhage." Of this Jose remarks: "We are the proletariat of the world. This is our shame and our pride."

When Jose and I last had lunch together at a local Japanese restaurant, he spoke about nationalism and Filipino pride. "How can we send our women to Japan as prostitutes? How can the people in power face the reality of that fact?" he asked. "I am ashamed every time I think about it," he hastened to add.

Through the many years I have known F. Sionil Jose as a mentor and a friend, our conversations have covered a wide range of subjects. There are the remembrances of his days as a struggling journalist, his encounters with the elite and the powerful during his stint as the managing editor of The Manila Times Sunday Magazine. There are the anecdotes of his association and friendship with fellow academics from the National University of Singapore, the University of California at Berkeley, or the De La Salle University in Manila where at various times he served as a professorial lecturer on Philippine culture.

Still there were other times when he regaled me with tales of his journeys to the old kingdoms of Bhutan and Sikkim, of the trials and travails of writing and the motley group of people that have crossed his path. Yet without fail, he returns to the subject of those sectors that have been left behind, the people he identifies with the most because he was once one of them. I ask him why we as a nation find ourselves in this predicament today. He never answers the question directly. Instead he goes back to history and recounts the many tales he has told so often — as if to say that we cannot find our way to the future unless we come to terms with the past.

He laments the fact that the village of his childhood has degenerated into a rural slum.

"When I was a kid, the poorest Filipino ate twice a day; now the poorest Filipino eats once a day — that is sad. In the 1940s, there were no women who worked abroad as prostitutes," he says. There is a certain hollowness inside, he admits. Though he left the countryside long ago, the land of his youth and the plight of his fellow villagers are burned in his memory. He routinely visited his hometown of Rosales in Pangasinan to listen to the language of his youth and to regain his bearings. But between the memories and the moments of hope, disillusionment sometimes takes over.

Just before we ended our lunch, I asked him to ponder on the meaning of his life's work. I asked him how we Filipinos continue to hope and keep faith alive. "That's what I've been trying to do," he says. "I'm trying to show how Filipinos can persevere, how this nation can redeem itself, how Filipinos can have a nobler image of themselves. But what happened?" The words that he hoped would awaken the consciousness of a people have fallen on deaf ears.

"Words are not enough, they are never enough," he tells me as we part ways.

Editor's note: This essay appeared in the book Between East and West published by Anvil Publishing, Inc. in 2007.