Should I stop listening to my favorite band once they’re ‘problematic’?

In the past few months, we have seen comebacks from well-loved artists in indie OPM, such as the iconic reunion of IV of Spades with Aura, and even Ourselves the Elves’ comeback gigs. These have definitely elicited the same schoolgirl gushing that bubbled within my younger self, who saved up every bit of my allowance just to attend gigs.

However, these trips down memory lane also remind us of artists who are no longer on the scene, for good reason—one of which is Ang Bandang Shirley, who made up a good chunk of my high school playlists and memories.

The band, along with Ourselves the Elves, Cheats, Coeli, B.P. Valenzuela, Shirebound and Busking, serve as a time capsule for simpler times, years before the pandemic and adulthood. They soundtracked countless nights of getting ready with my girls, singing, doing each other’s makeup, and drawing eyeliner that was way too long. They remind me of late nights, cramped inside Mow’s at Maginhawa with a beer in hand. Or even a birthday gift from my best friend that turned out to be a gig at Conspiracy along Visayas Avenue, where we stayed until the wee hours of the morning just to see Munimuni perform.

When I think of Ang Bandang Shirley, one of my favorite bands at the time, I remember being overjoyed at my 11th-grade school fair, where they performed. As clichéd as the story goes, I was nursing a heartbreak from someone whom I never truly dated but wasted my time on. Every time I hear Nakauwi Na, I am brought back to that moment, a slight sting and, honestly, a sh*t-ton of amusement at how much importance I had placed on such a trivial thing.

Now, more often than not, I wonder if revisiting my favorite Ang Bandang Shirley songs, such as Umaapaw, Nakauwi Na, and Actually, is considered acceptable. How am I supposed to reconcile the gap between wanting to listen to this band and the unwavering belief that they should be held accountable for all their alleged abuses and transgressions?

Ang Bandang Shirley officially disbanded this year after grooming allegations against the lead vocalist, Ean Aguila, resurfaced. Back in 2017, alongside the hype for the local band scene, chaos ensued on social media. A series of posts exposing bands and artists for sexual misconduct started taking over everyone’s feeds—among them were Ang Bandang Shirley members Aguila, Owen Alvero and Joe Fontanilla. They faced allegations of grooming, revealed by screenshots of inappropriate conversations with young fans that border on predatory. The band decided to release a statement denying the accusation of predatory behavior; rather, they redirected the conversation to how their “misconduct contributes to a larger culture of toxic masculinity that allows for these problems to perpetuate.” Aguila, Alvero, and Fontanilla issued individual statements, too—all of which were short messages full of apologies, sadness, and a promise of reflection.

The emergence of cancel culture has provided an avenue for strict accountability but also immense judgment. I have always stood by my morals and my beliefs—one of them being my hatred for men in a position of power who exploit women. However, it is not a clean-cut decision nor an easy one. I am once again stuck asking myself, “Am I still allowed to listen to bands that are considered monstrous?”

“For teenagers, music makes a kind of repository for feelings, a place for feelings to live, a carrier. So a betrayal by a musician becomes all the more painful — it’s like being betrayed by your own inner self.”

Claire Dederer wrote this in her book Monsters: A Fan's Dilemma, where she also talks about her positionality as a woman and a fan. “When I come to this question—the question of what to do with the art of monstrous men—I don’t come as an impartial observer. I’m not someone who is absent a history. I have been a teenager predated by older men; I have been molested; I’ve been assaulted on the street; I’ve been grabbed and I’ve been coerced and I’ve escaped from attempted rape,” she writes. “I don’t say this because it makes me special. I say it because it makes me non-special. And so, like many or most women, I have a dog in this particular fight: when I ask what to do about the art of monstrous men, I’m not just sympathizing with their victims—I’ve been in the same shoes, or similar.”

As someone present at Ang Bandang Shirley’s gigs as a young female fan, the situation feels eerily close. I am filled with the familiar feeling of disappointment, disheartenment, and a heavy acceptance of the perception of older men towards young women. These perceptions manifest daily, from micro-predations through staring, whistling and catcalling, to skin-crawling acts of grabbing, coercing and manipulation to send, to “talk,” and to satisfy. These musicians, who are under public scrutiny for allegations of sexual misconduct, grooming, or something worse, maliciously exploit a younger woman’s admiration and love to their advantage—they feed off these women’s vulnerability to appease their sick desires.

Maybe art transcends its creators. Once a piece of work has been put out there, the audience, in one shape or form, has made it their own.

Ang Bandang Shirley, Ean Aguila, Owen Alvero, and Joe Fontanilla are not the first and will not be the last to face scrutiny for the same abuses. The problem lies in the system that continues to allow these men to victimize vulnerable young women with little to no repercussions. As a woman, I feel disappointed with Ang Bandang Shirley for essentially sweeping it under the rug back in 2017. I feel immense anger towards Aguila’s abuse and sheer audacity.

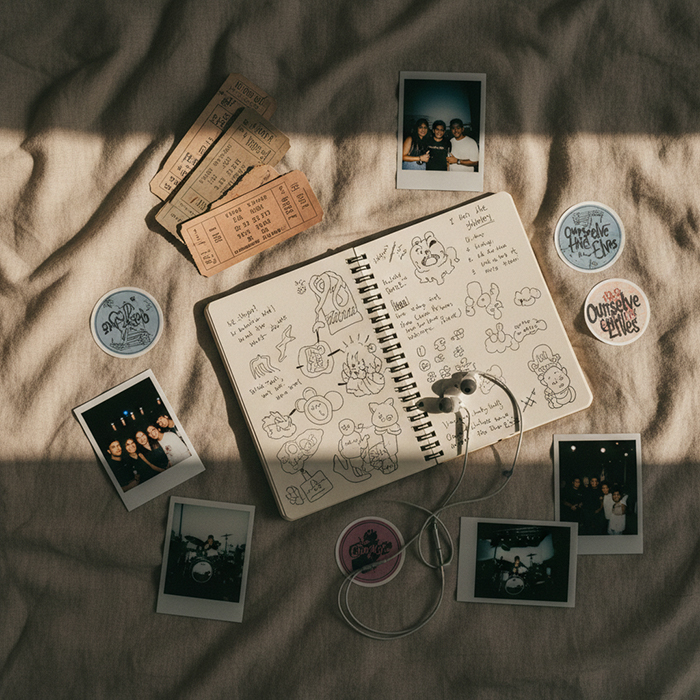

It would be easy to simply take the morally superior route and say that I will boycott them, but that would be lying to myself. For a time after high school, I was slowly letting go of their music—I was growing up, expanding my music taste, entering college, and meeting new people. However, while I do not actively seek them out anymore, they still reside in playlists, in memories, in realities that I once lived. It creates a sense of dissonance; I have kept their songs in memorabilia that haunt my room, such as photos, merchandise, stickers, and even people I once knew. These feelings are not tied to the horrendous acts of Ean Aguila and company, but rather of a time in my life they just so happen to play a part in. It is simply human to selfishly consume despite all of it.

This is not to say that any art is separate from its artist. Instead, maybe art transcends its creators. Once a piece of work has been put out there, the audience in one shape or form has made it their own.

As eloquently stated by Dederer, “Consuming a piece of art is two biographies meeting: the biography of the artist that might disrupt the viewing of the art; the biography of the audience member that might shape the viewing of the art. This occurs in every case.” My case is no different: my biography and the art I have consumed are not two different entities. They are forever intertwined. The art is shaped by my experiences with it and by it. Through this, it would no longer be a realistic solution to simply boycott or cancel the art and the artist. Perhaps it helps that they are already disbanded, frozen in time with only their old songs to keep sentimentality company. There is no longer fuel to actively support them, no new releases to bring in old and new fans alike, no new memories created, and in turn, no more avenue to perpetuate an environment wherein they can prey on fans. A disbandment creates the distance between them and me; they no longer feel like a looming presence but rather a nostalgic memory that no longer feels tangible.

I have found a pocket of peace knowing that my dilemma remains a constant conflict within a vast majority of fans—as per Dederer, I am not unique. I am not here to dictate how you deal with your own dilemmas as a fan. I am merely a voice that reassures you are not alone, from one fan to another.