Can truth be taught?

How prepared is our current education system in battling rampant disinformation and historical distortion? How do we equip the next generations to not only seek truth but actively advocate for it?

We spoke with five educators: Glenn Diaz, who teaches literature and creative writing; independent filmmaker and professor Sari Dalena; and Beatriz Gulinao, Mark Richardson Rovillos, and Rizalyn Camacho, who all teach social sciences.

In what ways does your field help uphold the truth?

Sari: As an educator and a filmmaker, the medium of documentary is a powerful tool to archive history as well as unearth perspectives that may not have been considered before. There’s an urgent need for filmmakers and film educators to take the difficult path of becoming memory keepers.

Beatriz: Education provides space for students to ask questions and equips them with the skills to answer these questions. Specifically for history, there’s the stress of truth-seeking; this skill helps students navigate the many sources of information out there, assess its quality, evaluate biases, figure out how they can answer these questions, and continue asking more questions.

Glenn: The approach to truth when you come from the point of fiction or literary studies is not always straightforward. Narratives are constructed (so) they’re very political, prone to being manipulated, and therefore can be weaponized. The body of work that we have, it’s very important to not just get students to read them but to teach them in a way that converses with the present.

Five educators discuss how truth is upheld in and out of the classroom. Art by Layne Yap.

How would you evaluate the current education system on how accurately and comprehensively history is being taught? Are academic censorship and historical revision threats to Filipino students in particular?

Mark: I’ve been teaching history for the past 16 years and I’ve witnessed how the curriculum has congested topics in history—(it’s been) relegated to lower grade levels and history as a subject was removed in high school and college.

Beatriz: How we view education is a more insidious threat (than academic censorship). Sometimes it’s seen as just a means to an end: it’s so students can graduate, get into a good college, (and then) a good-paying job. We’re not really putting value into truth-seeking. To address that, so much more has to be done elsewhere—it can’t just be the burden of teachers finding the right textbooks or making perfect lesson plans.

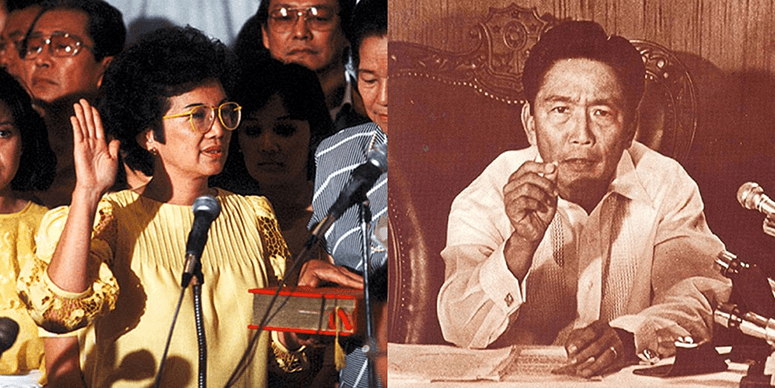

Sari: I always tell my students how Philippine cinema helps shape our historical and political landscape. Ferdinand Marcos had a biopic, a propaganda film called Iginuhit ng Tadhana from 1965 that received tremendous popular support. Then the Estradas, Revillas, and Ejercitos built their mass-based followings through comics and fantasy movies like Panday, Geron Busabos, Ang Batang Quiapo, and Asiong Salonga. Cinema is their origin; they solidified their populous appeal at na-shape nila yung core values and taste (ng mga Pilipino). Based from my experience teaching Philippine cinema and history, napakalakas talaga ng image-based, immersive approach sa pagtuturo ng kasaysayan instead ng mga traditional textbooks.

Glenn: There is a danger of history devolving into personalities. For instance, we see very complex historical ideas or periods reduced to Marcos vs. Aquino—in such a way the system evades scrutiny because na-reduce to bida vs. kontrabida. (In teaching history,) there has to be a reckoning; (students must be able to) connect things from the past to the present and see how the things we are experiencing today are symptomatic of unresolved stuff from the past. I suppose artistic products are one way to do that.

“So much more has to be done elsewhere – it can’t just be the burden of teachers finding the right textbooks or making perfect lesson plans.”

Mark: If we would like to evaluate history education, I hope we also look at how teachers are taught to teach history. Sabi nga nila, you cannot give what you do not have. I think we’re fortunate that a lot of teachers right now are trying to incorporate musicals, mga pelikula, even works of art (tulad ng) mga painting.

Rizalyn: As a Philippine Politics and Governance teacher in Grade 11, I have to reintroduce (my students) to Philippine history before we can go on to a deeper discussion (about politics and governance). There’s this lack of planning on how history can be taught in different subject areas, especially when K-12 was implemented. The Philippine Politics and Governance subject is also only offered in the Humanities and Social Sciences (HUMSS) senior high school strand when it’s also relevant to other strands like Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) and Accountancy, Business, and Management (ABM).

Outside the classroom, are there other ways for the youth to learn more about history in a way that is unbiased or uncensored?

Sari: Dito papapasok yung dedication natin sa historical spaces. When I was in Berlin a few months ago, I was very moved by how they were able to intentionally retain many of the painful locations associated with the Holocaust. May pinuntahan akong crematorium that they transformed into a cultural space – imagine this haunting place is now a space dedicated to the arts which allows citizens to confront their traumatic pasts. Dito naman sa atin, parang hindi gumagalaw yung mga plano. Saan natin dadalhin yung mga bata?

Mark: We have plenty of these historical places, but how do we make these historical spaces relatable to our students? They see these as monuments; they’re not connected with them. Yung pag-equip sa mga estudyante to be able to relate what happened in the past to what is happening in the present, doon nakikita yung value kung bakit sila pumupunta sa isang lugar.

Glenn: History is all around us. Sometimes there is also a fetish towards a national narrative at the expense of local histories. That’s also one crucial thing that students can think of: whatever small town or city that you are in, I’m pretty sure may kasaysayan din doon.

Beatriz: I think there’s no way to learn about history that is unbiased or uncensored. For example, as teachers, (because of the) limited time we have in the school year, I need to make choices about what my students read and what we talk about in class. Those choices reflect my values and my biases. Every time someone makes a film, writes a novel, or curates a museum, it will always be a reflection of their values and their biases. Dapat ‘yun ang mindset when you go outside the classroom and you try to learn more, na laging may natitirang curiosity. You accept that it’s never going to be unbiased and perfect, and that’s why you need to continue to pursue truth.

“I always invite students to make their individual experiences more meaningful by connecting them to broader and more collective narratives.”

How can the youth utilize social media to fight disinformation and promote truth?

Beatriz: I can see how (social media) sets an avenue for engagement, but maybe it’s not the best place for difficult conversations. If we will use it to promote truth, we (must) take time to learn first, then we speak only when what we’re going to say will add value to the discourse. We need to have the patience to keep the conversation going even when the hype is over. It needs to come from a place of sincerity; we’re not there to just prove a point.

Sari: Napaka-tricky talaga ng role nitong social media in discerning fact from fake news kasi it’s not just the kabataan, even mga titas and titos natin, (hindi nila alam) na fake news na pala yung sine-share nila. Ang nakikita ko lang talagang way to reverse this is we have to embrace the platform. We have to accept na ito na yung armas ng mga kabataan, so now let us teach them how they can use it to promote truth.

What are some actionable steps students and young people can do/be part of to join the fight against disinformation?

Mark: Our classrooms should model how we can engage in healthy discussions with people that have different opinions, and we should be able to moderate that as teachers. At tayong mga guro, (dapat) may kapasidad mag-discern ng impormasyon na ginagamit natin sa classroom.

Glenn: I firmly believe that history enlarges the present reality. I always invite students to make their individual experiences more meaningful by connecting them to broader and more collective narratives. And I believe that the fight against disinformation is in point with other fights, such as the broader improvement of the basic conditions of every Filipino. I suppose in the broader scheme of things, when you think about the recent presidential elections, many of us were struck by just how huge the machinery is that we’re up against – sobrang well-funded (and it was) years, if not decades, into planning. It’s hard to go against that just by ourselves, so a very concrete thing to do is join organizations that share your political beliefs or visions of society.

Sari: One of the strongest ways to fight disinformation is to take advantage of the wealth of sources that we have. Napakaraming martial law films, pero nasaan ang access? Bring these to schools, universities, and libraries – contact the producers. Yung mga educational videos about the Philippine-American War, the Japanese occupation, the regional conflicts, and the peasant uprisings, gawan ng mini docus, ng animations, anything that will get young people to absorb it. Pwedeng pwede pa natin ito labanan talaga. We just need to work together.