‘Filipino Time’: Is it time to change this tardy tradition and unfair name?

Do you know the Philippines officially observes "National Time Consciousness Week" during the first week of January? I believe it’s a moment of reflection on our collective relationship with time. Proclaimed under Republic Act No. 10535 in 2013, the initiative aims to nudge us Filipinos toward punctuality. But is this effort a Sisyphean task or a timely intervention? (I must confess, this writer has often in the past been guilty of this bad habit.)

Let’s unpack the humor, history and hope wrapped in our so-called "Filipino Time."

A legacy of lateness

The term “Filipino Time” was allegedly coined by American colonizers when they conquered our archipelago in the 1900s, and it has long been associated with a casual disregard for punctuality. However, during the Spanish colonial era, do you know tardiness was not just a habit—it was even (shockingly!) a status symbol?

Dr. José Rizal highlighted this in El Filibusterismo novel, where a latecomer to a theater performance exuded the arrogance of someone asserting their superiority through lateness.

The more laid-back Spaniards bequeathed us with the "mañana" habit, the art of procrastination wrapped in shrugs and promises to get it done tomorrow. Add to this our soporific tropical and often humid climate, which seemingly invites a leisurely pace, and—voila—a cultural cocktail of lateness emerges.

Even our own history is peppered with infamous anecdotes. In 1949, President Elpidio Quirino arrived two hours late to receive an honorary degree at Fordham University in New York City. By the time he arrived at 4 p.m., much of the audience had already left. Talk about a missed opportunity!

When time stood still

This isn’t just a national quirk; it’s already a social contagion that even our ethnic Chinese minority has acculturated and even worsened. At Filipino-Chinese community events, I’ve noticed that our dinner receptions and wedding parties typically start two hours late from the time embossed at formal invitations—an amusing departure from traditionally punctual ethnic Chinese gatherings elsewhere from Singapore, Shanghai, Taipei to Hong Kong. Tourist guides in Guangzhou City once joked about this, asking me, "Why are Filipino-Chinese tour groups always late?"

And let’s not even start with our entertainment industry. The late actor Eddie Garcia, the late movie queen Susan Roces, and the now 91-year-old actress Gloria Romero, veterans of Philippine cinema, were paragons of punctuality. Yet, some younger and less famous stars arrive fashionably (or infuriatingly) late to shootings, oblivious to the wasted time of their peers and crews. There was even an actress who arrived at her own press conference four hours late!

The domino effect

Tardiness begets tardiness. If your meeting host arrives late, you might also adjust your arrival next time. Soon enough, entire systems adopt a buffer for lateness, normalizing the behavior. It’s what some economists might call "negative network effects."

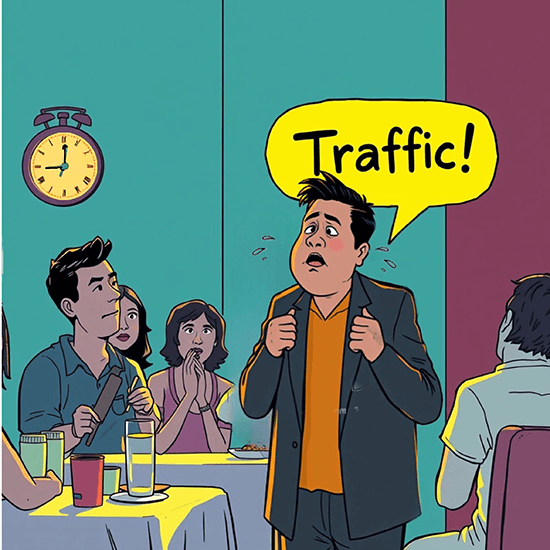

There are always excuses handy for lateness, such as “traffic.” Metro Manila’s infamous and horrendous traffic jams are often a legitimate excuse, especially during rush hours or the recent Christmas holidays. With an inadequate public transportation system and unpredictable, oft-mismanaged road conditions, plus occasional rainy floods, it’s challenging to adhere to strict schedules.

But is it really just traffic? Or has it become a convenient alibi to mask our fundamentally utter lack of respect for others’ time?

In fairness, not all Filipinos are chronically late. President Bongbong Marcos, like his late father Ferdinand E. Marcos and his elder sister Senator Imee Marcos, scores okay on punctuality. Former Presidents Corazon C. Aquino, Fidel V. Ramos, and Gloria Macapagal Arroyo also set good examples of timeliness.

If they can honor the clock despite their packed schedules, surely the rest of us can aspire to do the same.

Why it matters

“Filipino Time” isn’t just a cultural quirk; I believe it reflects deeper issues. Chronic lateness in this 21st century signals a lack of discipline and respect for others’ time. It cumulatively and collectively costs us economically, socially, and reputationally.

If we want to build a truly progressive and globally competitive nation, we must please stop tolerating—and worse, celebrating—this negative habit.

So how do we shed this unflattering and unfair label? Here are a few suggested steps:

- Personal accountability. Stop blaming "Filipino Time" and own up to our tardiness.

- Systemic solutions. Push for better, affordable public transportation and efficient urban planning.

- Cultural shift:. Redefine punctuality as a mark of professionalism and respect.

- Highlight good examples. Publicly cite leaders, business tycoons, and celebrities who are punctual as positive role models to emulate.

"National Time Consciousness Week" isn’t just about punctuality—it’s about valuing our own time and that of others, it’s also about modernizing and strengthening our Philippine economy and a culture of national efficiency.

This January, let’s earnestly make punctuality part of our New Year’s resolutions. Because in a country where "Filipino Time" unfortunately still reigns, being on time isn’t just about beating the clock—it’s about beating the odds.