A few moments before the clock struck midnight, Filipino policemen burst through a family home situated in the slums of Manila.

From the outside, nothing seemed out of the ordinary. But when they got to a compact room, it felt quite unusual with the things they unexpectedly found: laptops, webcams, Wi-Fi router, and, to their surprise, young girls and boys who “were about to undress and perform sex acts on each other, following instructions from a pedophile connected from overseas via webcam.”

The mastermind? One of the kids’ very own mom. She would receive money from the perpetrators via international wire transfer and reward the little ones with 150 pesos ($3) after every “performance,” which would take place as the mother of the other three children works hard outside Manila to meet their everyday needs.

It was seven-year-old Danilo (not his real name) who made his father aware of the “business,” prompting him to alert the police.

The operator’s daughter—nine-year-old Jennifer (whose name has been changed)—was tight-lipped throughout the raid, in hopes of shielding her parent from any kind of attack. It took her a few therapy sessions alongside the other child victims at the Child Protection Unit of the Philippine General Hospital before she finally decided to talk about it:

“I never knew it was wrong, what my mother asked me to do,” she said. “I just thought we were having a show.”

The state of OSAEC in the Philippines

Online sexual abuse and exploitation of children (OSAEC) has been a real menace in the Philippines, even more so during this time of limited movement and financial desperation.

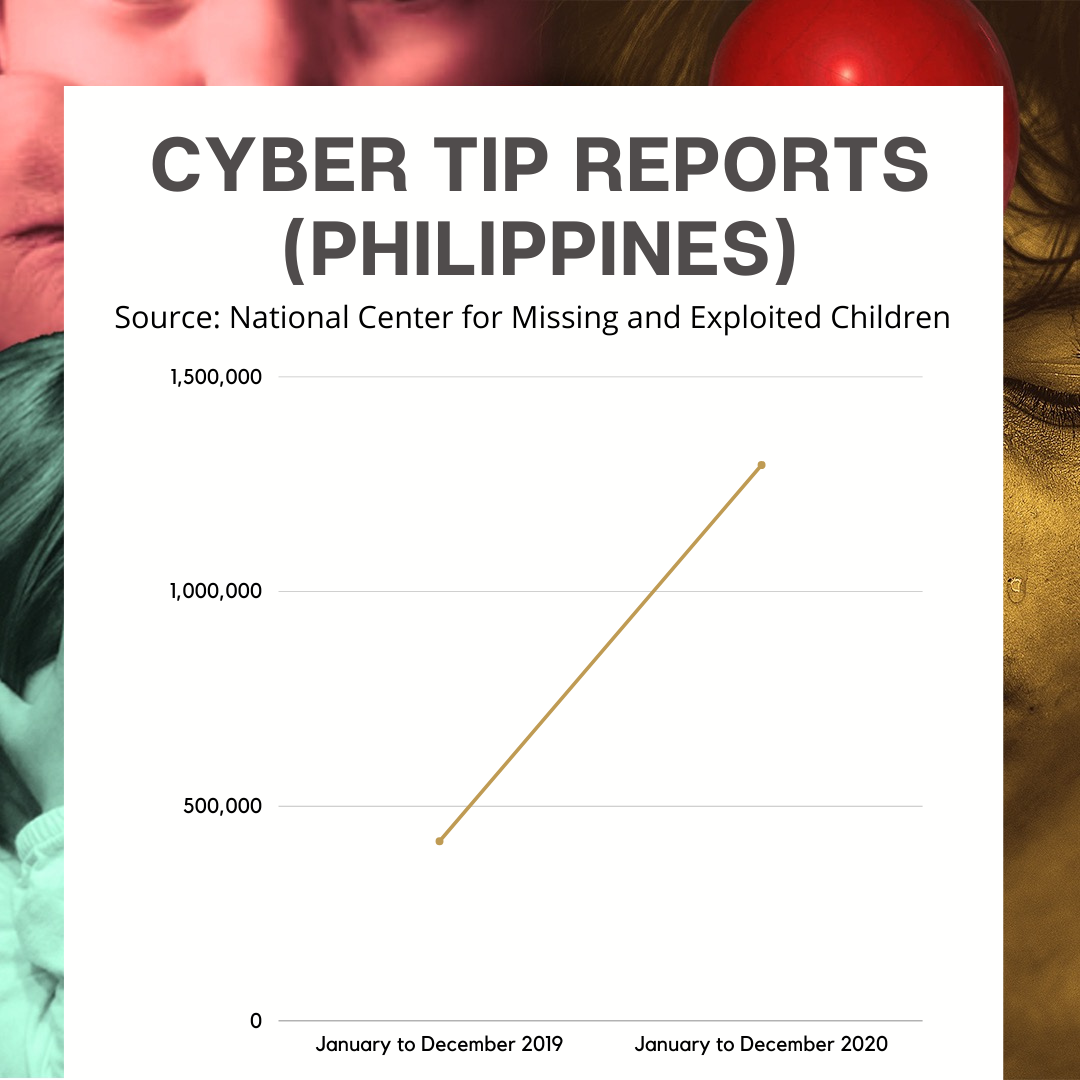

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) reported a 209% increase from 2019 to 2020 in the cyber tip reports in the Philippines, with a total of 1,294,750 cyber tips in January to December 2020, compared to 418,422 cyber tips in January to December 2019.

What are cyber tips? UNICEF referred to such as "reports made by the public to the NCMEC on child abuse being committed with the use of their systems. The NCMEC requires ISPs and ESPs in the US to submit reports of child abuse."

In only the first semester of 2020, the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) disclosed suspicious transactions amounting to P113.1 million in line with child pornography. The AMLC recorded P65.8 million of such in 2019, indicating a 156% increase.

Save The Children Philippines, just recently, called on the public to join its campaign aimed at making the Internet a safer environment. The independent organization for children stressed that more young people are at risk for OSAEC amidst the COVID-19 pandemic “as families resort to easy money due to deepening poverty, while children are still not allowed to leave their homes.”

Atty. Alberto Muyot, its Chief Executive Officer, said it’s no longer a health crisis—it’s a child rights crisis that needs immediate attention, too. “Online sexual abuse and exploitation of children is a silent pandemic that has permanent and devastating effects on children’s mental health and psychosocial well-being,” he declared.

In an exclusive interview with PhilSTAR L!FE, Irene Dumlao, the OIC-Director of the Department of Social Welfare and Development’s (DSWD) Social Marketing Service, revealed that some were given P100, while others received up to P3,000 per show. Such rates were based on reports by the IACACP as well as interviews with OSAEC victims conducted by PNP and DWSD’s social workers.

Additionally, Jenna Serrano of End Child Prostitution and Trafficking (ECPAT) Philippines told PhilSTAR L!FE that in some cases, operators and traffickers “would give child victims a very small amount compared to what they are getting or tokens such as candies, toys, and cellphones.”

Who are the usual perpetrators or traffickers? The DSWD pointed out peers and relatives, typically in the family circle. “They serve as ‘facilitators’ as they groom, lure, and force their children into OSAEC.”

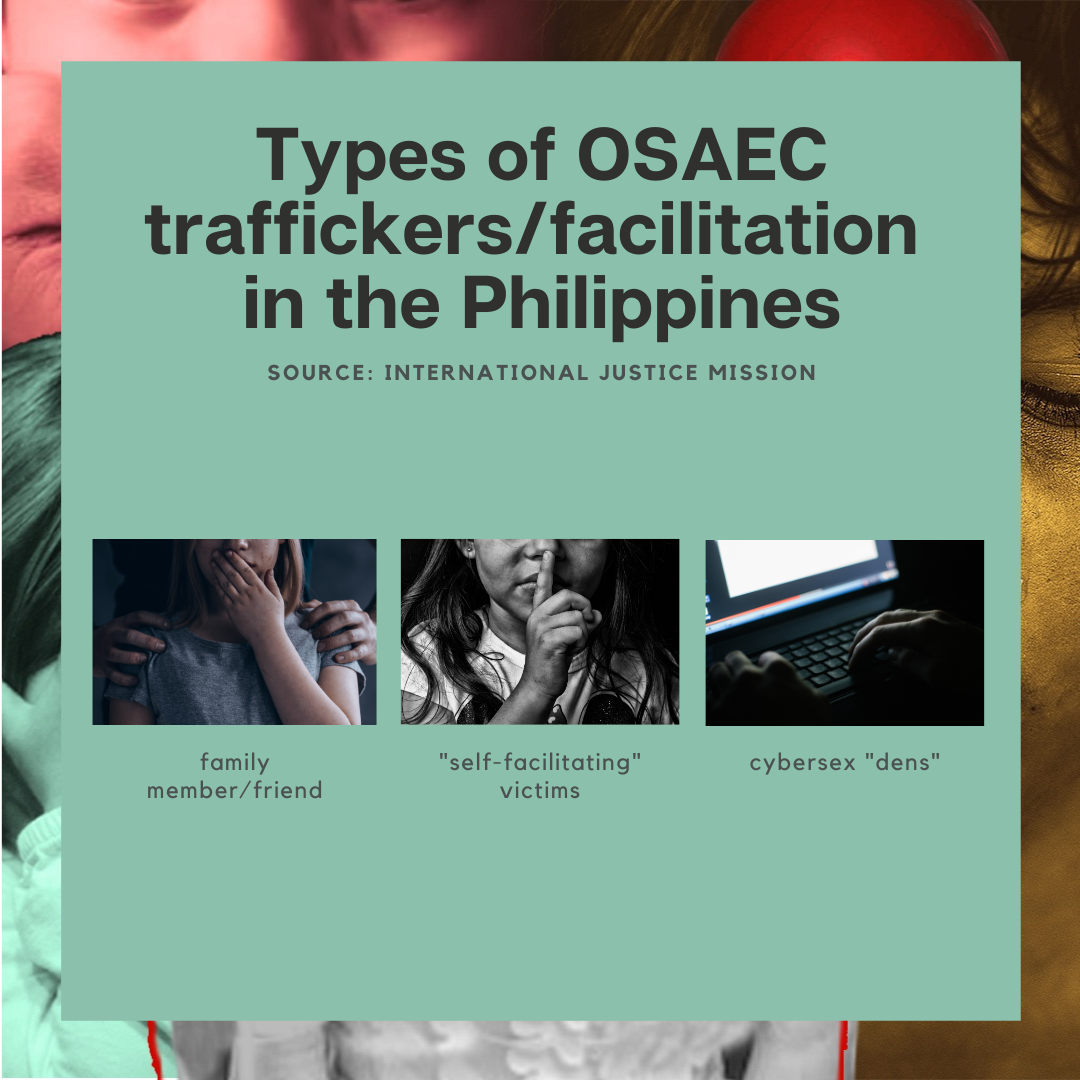

In an OSAEC study led by the International Justice Mission (IJM), the authors stated three types of traffickers in the Philippines, as identified by Terre des Hommes research.

The “self-facilitating” victims are “older teenagers sending material to foreign customers. By definition, the teenagers are minors and legally considered trafficked,” according to the journal. “This does not take into consideration any grooming that might have taken place or manipulation to self-generate the material.”

Furthermore, the researchers noted that such material does not always indicate OSAEC—“there are cases where the children are too young to be facilitating the financial transaction and there is an adult involved, while not known to the customer.”

Some people are being held in “cybersex dens” for international audiences, which are usually managed by crime groups and foreign nationals. “Other establishments like ‘dens’ are internet and PisoNet cafés,” the study read. “These cafés provide easy access to the internet that, while there is an attempt from managers to monitor the contents and activities conducted, have been known to be used for grooming and child sexual exploitation material.”

The same study found that global law enforcement data, which was identified in seven OSEC source countries between 2010 and 2017, "seemed to verify what OSEC investigators have long acknowledged: that the Philippines is an OSEC hotspot." This is because it "received more than eight times as many referrals as any other country identified."

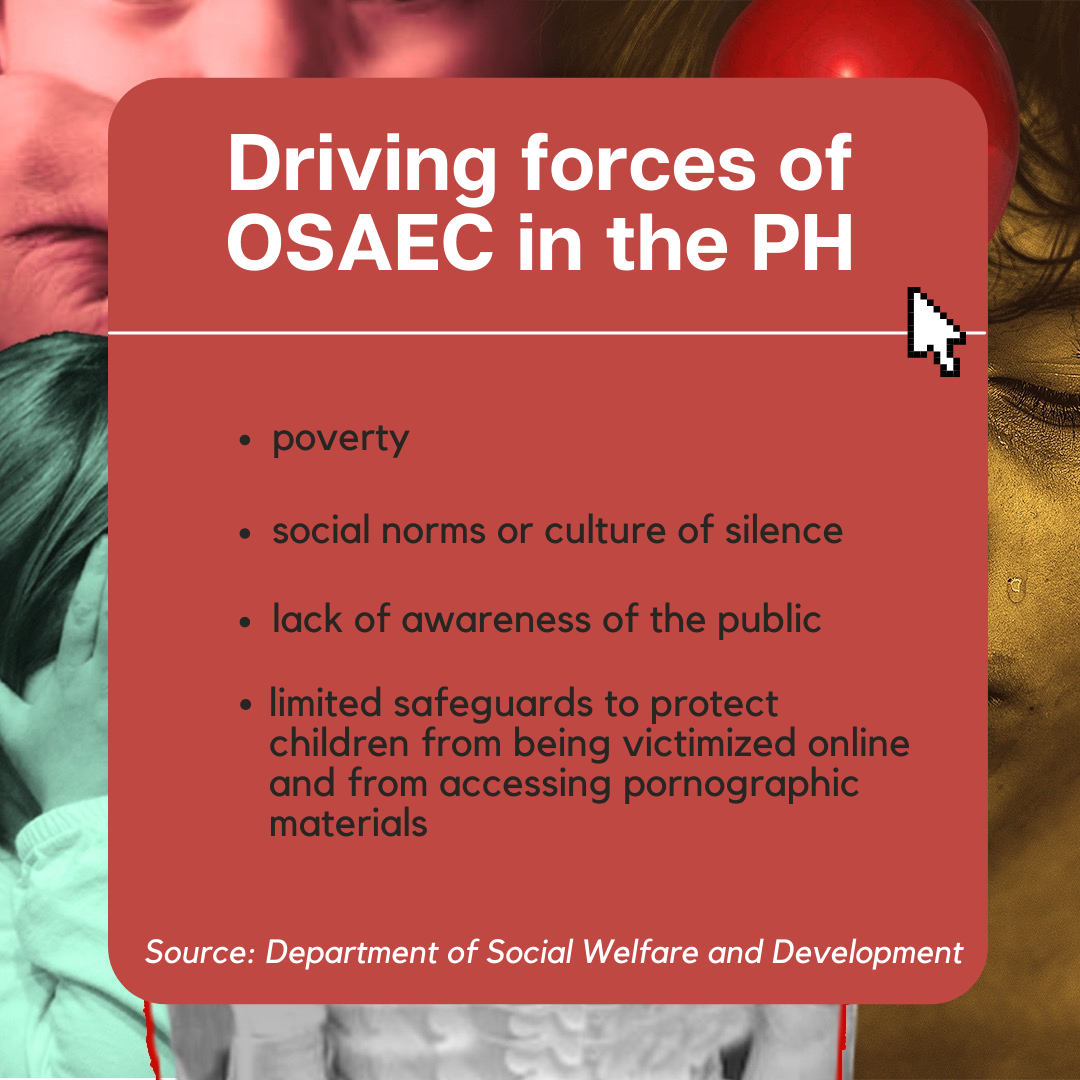

The DSWD pointed out the following as the driving forces of OSAEC in the Philippines:

OSAEC, stressed the DSWD, could have a long-term impact on the victims. Apart from maladjustment, low self-esteem, depression, sense of self-blame, guilt, shame, and psychiatric illness (based on the 2nd National Plan of Action for Children 2011-2016, 2016), it may also bring about feelings of isolation and stigma, trust, dissociation, symptoms of post-traumatic stress, and relationship difficulties (Glarino, Davis, Sabahoglu & Nels, 2017). Another study (Diloy, 2013) found it may “contribute to the view of the child that having sex with people does not necessarily require deep affection between the couple.”

OSAEC cases in the country

The youngest OSAEC victim that has been rescued in the Philippines is—shockingly—a two-month-old baby. This was reported by the IJM via a case work, where it was stated that “47% of cybersex trafficking victims rescued have been 12 years old or younger.”

Serrano said that they assisted a six-year-old, but victims can be way younger. “Very young victims become the criminals’ ideal prey because they can’t speak out. They are also easier to manipulate—they often do not understand that they are being abused,” continued Serrano. “They are made to believe that they are only helping their families have food on the table or pay the bills.”

There are times that the perpetrator would even request the victim to have sex with another child in front of the camera, noted ECPAT’s social worker Trinidad Maneja.

Some OSAEC cases have turned into actual abuse. Australian child sex abuser Peter Scully, for one, “was sentenced to life imprisonment after being convicted of one count of human trafficking and five counts of rape” in 2018, as written in an ABC News report. He was arrested by Filipino police in 2015 for sexually abusing children—with an 18-month-old infant as his youngest victim. The Guardian said a 12-year-old was even found lifeless in the kitchen of a house he rented in Surigao.

In 2020, David Timothy Deakin was likewise sentenced to life imprisonment for “sexually exploiting Filipino children using webcams to sell videos, photos, and livestreams to buyers abroad.” AP News wrote in an article that during the raid, the anti-human trafficking force found children’s underwear, toddler shoes, cameras, bondage cuffs, fetish ropes, meth pipes, stacks of hard drives, and photo albums in his Pampanga home.

What’s being done to curb OSAEC?

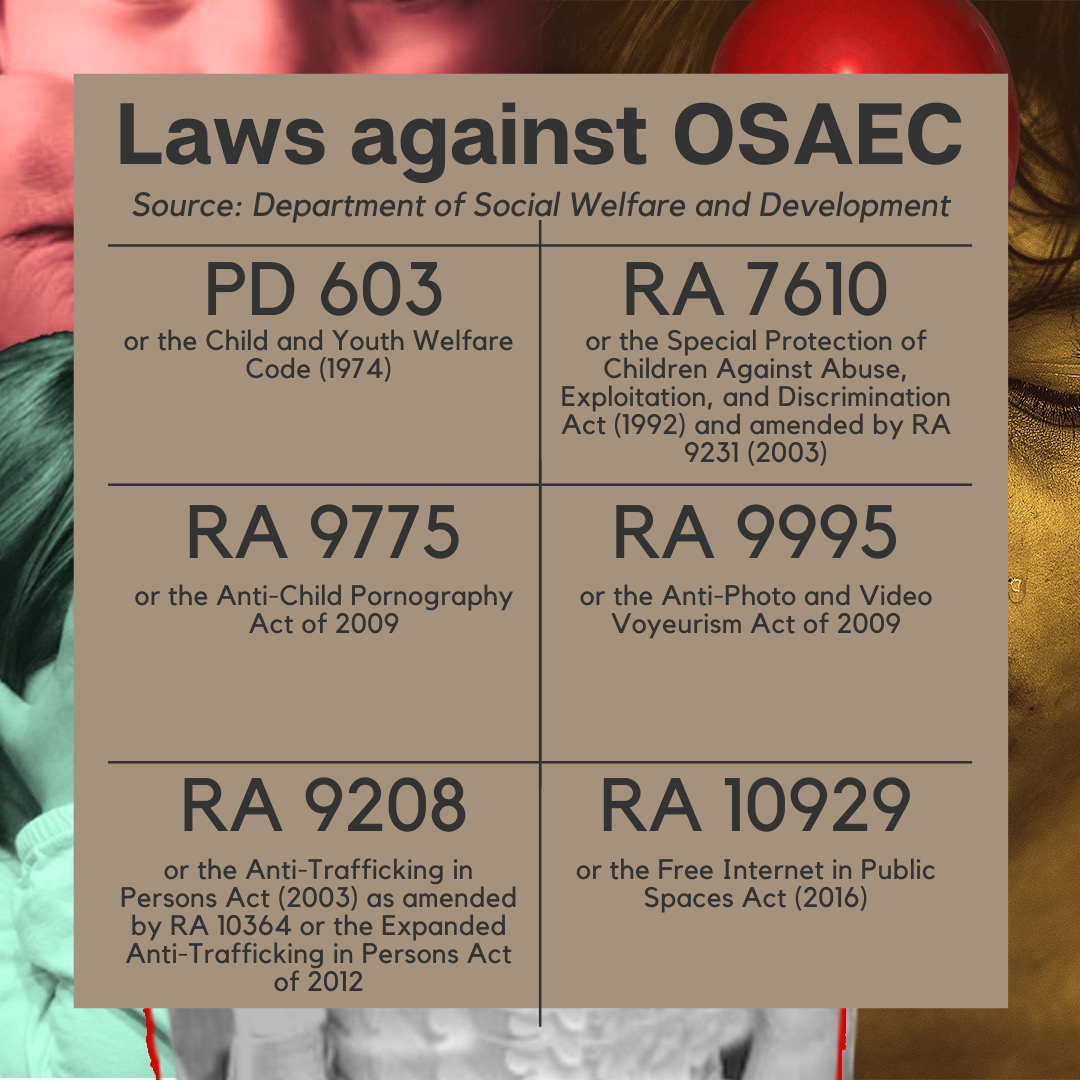

There are a number of laws against OSAEC in the Philippines.

The DSWD, as the IACACP chair and the lead agency in the social protection of vulnerable sectors, is working closely with the PNP and the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) as well as local government units (LGUs) like the Local Council for the Protection of Children (LCPC) to monitor the perpetrators and rescue the victims.

"Over the years, the Department has intensified its coordination with IACACP member-agencies to address the problem of child pornography," Dumlao shared. "Among the major accomplishments of the Council was a strengthened advocacy for the prevention of child pornography through various platforms, including the formulation of a National Response Plan (NRP) for Online Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Children (OSAEC) 2016-2020."

On Feb. 5, 2018, the Duterte administration issued Proclamation No. 417 declaring every second Tuesday of February as "Safer Internet Day for Children Philippines."

Despite such efforts and laws, it’s been quite difficult to track down.

"Sexual predators learn through time," Richard Dy, spokesperson of Child Rights Network Philippines, told PhilSTAR L!FE. "As technology advances, so does their knowledge to hide their tracks and evade accountability. So does their techniques—now, we have livestreamed sexual abuse, online grooming, and sextortion."

“The advancements of technology, proliferation of social media applications that are hard to monitor, newer hardware and software, and online money transactions make it more difficult to detect OSAEC, particularly livestreaming at present,” said Dumlao.

In January, Malacañang ordered the National Telecommunications Commission (NTC) to penalize internet service providers (ISPs) that allow their platforms to be used for OSAEC. Cabinet Secretary Karlo Nograles stressed that the growing problem has caught the attention of President Rodrigo Duterte.

Early this month, Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra disclosed that several measures that he put up with his department on OSAEC crackdown has received approval from the President. Apart from the aforementioned NTC order, their recommendations include issuing an executive order (EO) “strengthening cooperation” among the Inter-Agency Council Against Trafficking (IACAT), the IACACP, and other important agencies as well as prioritizing the passage of bills “amending the anti-trafficking in persons act, so that human trafficking, particularly sexual exploitation of children, will be exempt from the provisions of the anti-wire tapping law.”

In his official website, Gatchalian—who filed the Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) Card Registration Act in 2016 and refiled it in 2019—threw light on the importance of having a SIM card registration law, citing a 2014 study, which found that for OSAEC, potential perpetrators make use of disposable or prepaid SIM cards that don’t need any form of registration in some countries. “Kung magiging batas ang pagpaparehistro sa mga SIM card, mas mahirap nang makapagtago at makatakas ang mga traffickers na umaabuso sa ating mga kabataan,” declared Gatchalian.

How can we help?

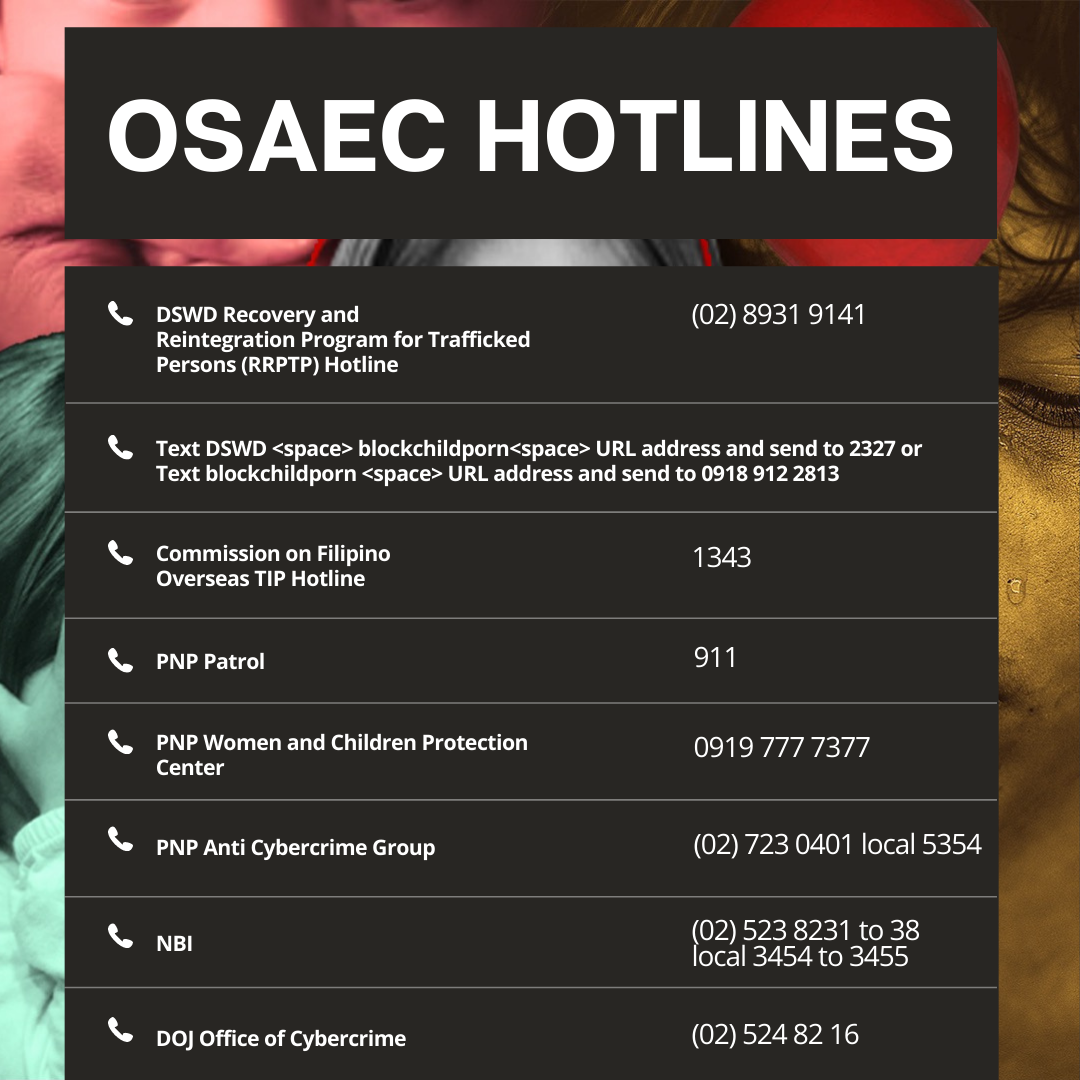

The DSWD highlighted the need to come together on a national and global level in combatting the problem. To report cases of OSAEC and other forms of abuses against children, you may contact the following hotlines: