Product placement: The other lead star

I think I’m not the only one who has noticed an increasing number of product placements in streaming shows, be they Western or Asian. At first amusing, they have quickly progressed from distracting to annoying.

Even as the golden age of television enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with the advertising industry—with TV commercials and catchy lines and jingles becoming parts of pop culture—many rejoiced when it inevitably yielded to cable service and later to streaming, precisely because of the absence of commercials.

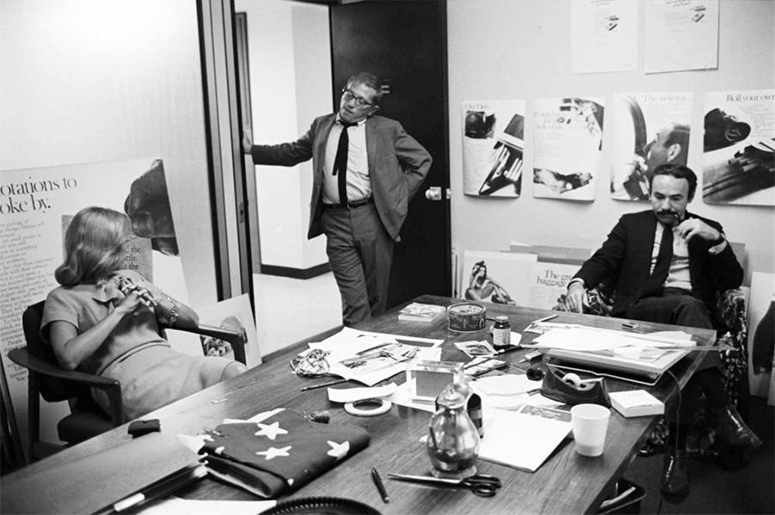

But the gods of Madison Avenue—together with all the Mad Men (and Women) of the world—wouldn’t be easily silenced. By breathing new life into an old ploy and using subtle (indirect) as well as not-so-subtle (blatant, sometimes written into the dialogue) methods of introducing their clients’ products to millions of regular viewers, they are able to create a subliminal space where a product shares the same glamorous frame as beloved characters.

In the long, glittery history of entertainment, brands have always had a knack for finding the spotlight. Long before “influencer marketing” became a buzzword, product placement or PPL—the art of slipping a branded good into a film, TV show, or streaming drama—was already alive and thriving.

The practice is almost as old as cinema itself. In 1896, the Lumière brothers—inventors of the Cinématographe, an early motion-picture camera and projector—reportedly featured Lever Brothers’ Sunlight Soap in one of their short films. Through the years, some partnerships have become iconic.

James Bond had his Aston Martin DB5. Dominic Toretto drove his Dodge Charger throughout the Fast & Furious franchise. John Wick’s 1969 Mustang is practically a co-star. Reaching 88 kph was a piece of cake for Doc Emmett Brown’s DeLorean in Back to the Future. And those icons of cuteness, the VW Beetle Herbie and Mr. Bean’s Mini Cooper, spawned generations of enthusiasts.

Beyond cars, beverages had their own cinematic cameos: Coca-Cola and Pepsi jostled for screen time, Heineken bought Bond’s loyalty, and Starbucks photobombed a Game of Thrones episode (whether it was intentional or an honest mistake is anybody’s guess, like Coldplaygate).

Fast food chains jumped in as well, from Iron Man craving Burger King after his desert escape to Harold and Kumar embarking on their now-legendary pilgrimage to White Castle.

One thing’s for sure—it was in the 1980s that the practice went truly mainstream.

In E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), the unforgettable moment where Elliott lures E.T. out of the woods with a trail of Reese’s Pieces—coupled with the “ugly” face of E.T. on every bag of the same product outside theaters—was a marketing gamble that truly paid off for Hershey’s. Within weeks, the snack flew off the shelves, boosting sales by over 65% and putting the brand on the consumer map.

Of course, not everything is sweet and happy in advertising. A study by Mekemson & Glantz found that the tobacco industry, recognizing the promotional value of portraying smoking in films and TV, had actively built ties with Hollywood. So, around the time E.T. was making kids smile with their Reese’s Pieces, Big Tobacco was hiring professionals to secure positive on-screen depictions, avoid negative portrayals, and even supply free cigarettes to actors. While the industry claimed to have ended such practices, smoking in films rose through the 1990s, slowing down only when smoking in public eventually became un-PC.

Across generations and oceans, Asian studios have turned product placements into both an art form and a global export scheme. I spend an inordinate amount of time watching K-, J-, and C-drama in various streaming services. My wife and I discovered that the more episodes we watched, the more we were exposed to an endless parade of products being peddled surreptitiously as well as explicitly. Sometimes, they work, as when we suddenly crave the chicken being devoured on screen with a side of kimchi and soju.

How many times has Subway been drilled into our consciousness by Korean shows alone? With the growing global popularity of K-drama, it’s a masterful marketing strategy for an American brand to make its presence known through product placement riding the Korean wave. Here’s a sampling of Subway’s ubiquitous display: Guardian: The Lonely and Great God, Descendants of the Sun, Vagabond, Crash Landing on You, Record of Youth, My Girlfriend Is a Gumiho, See You in My 19th Life, and The Fiery Priest.

Certain shows feel like an entire department store squeezed into a script. The King: Eternal Monarch is the gold standard for maximalist PPL, featuring Georgia Coffee, J.Estina jewelry, Paris Baguette pastries, Aston Martins, Jongga kimchi, red ginseng, Cellreturn LED masks, Kahi skincare, The Alley milk tea, BBQ Olive Chicken, and even branded phone cases. You could fill your shopping list and order everything online while watching a single episode.

Other countries have given the practice their own cultural spin. Japan leans into everyday products—in the Yakuza franchise, for example, already popular household names like PepsiCo, Red Bull, Asahi, and Suntory make notable appearances. China, with its tighter advertising regulations, uses product placement as a form of soft marketing, embedding logos into sets and props. Digital technology now allows for “region swapping,” where a coffee cup might read Starbucks in the US but become Luckin Coffee in China, without the actors ever having touched either version.

We’ve had our own share of branded drama moments in Philippine cinema, the usual suspects being telcoms, beer, instant noodles, canned sardines, or one of the global Filipino brands like Jollibee. Sometimes it’s seamless; other times it’s almost comically obvious.

From a business standpoint, product placement is a win-win arrangement because it taps into the emotional connections viewers already have with a character or story. For filmmakers, the funding from PPL can offset massive production costs; for brands, the exposure can be international, long-lasting, and far more effective than any traditional advertisement.

But there should be a delicate balance between effectiveness and irritation. When integrated naturally, product placement can enhance realism, giving a story the same branded textures that real life has. After all, not everything has to be fictional—even citizens of Metropolis and Gotham City can enjoy real-life donuts and coffee on-screen.

The bottom line is, product placement is like the Force in Star Wars—always there, whether we notice or not. And to borrow from Darth Vader, “It is useless to resist.”