Nineteen seventy-two

In commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the declaration of martial law, PhilSTAR L!fe is publishing a series of essays written by personalities who experienced one of the darkest periods in Philippine history.

* * *

One of my first memories of martial law was the news of the landing of a helicopter in a vacant lot in our village, right across the home of an Air Force colonel. He had apparently been summoned and fetched.

The village, located south of Manila, was then sparsely populated, which made it easy to spot what was going on a block or two away. The news of the chopper landing was like that of a UFO dropping from the sky—it became the talk of the household and the village and shattered the calm of that Saturday, Sept. 23, 1972. It signaled that something was afoot.

I was 10 years old at that time, and what that something was would not be evident until I became a university student much later. It went largely unnoticed in places far from Manila and its peripheries, mainly because Ferdinand Marcos had shut down all sources of news and of truth. People would not have known, unless they had first-person eyewitness knowledge or knew someone that did, as in the chopper landing. This is one reason majority of Filipinos could say martial law never affected them or caused anything unpleasant. They were oblivious to its unfolding, except for the blip that was the momentary disappearance of broadcast and print media.

Before 1972, before our family moved to that village in the south, we lived in Manila where my grandfather was a fiscal. Ours was a big household always abuzz with children, house help and visiting relatives. Manila was then the center of mass media. Not far from my grandparents’ house was the Manila Broadcasting Company studio where audiences could come and watch radio programs being broadcast live. Watching the DZRH radio programs is one of the memories our elders mention when they talk about that time. The practice of visiting broadcast stations was passed on to our generation, as well.

I remember our grade school class trooping to a broadcast studio to watch a children’s program hosted by Maan Hontiveros. The nuns in my school apparently thought television was so important a medium they included it our curriculum, making us watch televised educational programs through a TV set that appeared in our classroom during the program’s time slot. The country’s growing broadcast industry was such an important part of life, that our elders would often point out broadcast buildings when we passed them on the road.

In those years of the middle to the late 1960s and up to 1972, the children in our family grew up watching television, where we learned of the news of the day—man landing on the moon, Gloria Diaz winning Miss universe, student rallies, the Plaza Miranda bombing—and educational and entertainment programs alike, such as Sesame Street, cartoons, American sitcoms, and action and drama series. I distinctly remember being sprawled in front of the TV watching a noontime game show with college students as contestants. Asked what brought them to the studio that particular day and hour, each one answered gleefully, “Boycott!” I heard the term often in those days and came to know what it meant. Protest was a way of life in the universities before martial law and was treated matter-of-factly by many.

In its form at that time, as source of information and entertainment produced independently by commercial stations, television provided Filipinos with a shared experience, a shared reality, although a reality experienced mostly by middle class, urban Filipinos.

Actually, what we didn’t see or read in the news, we saw or heard about in person or through word of mouth. My grandparents’ house stood along the route of rallies and marches of pre-martial law Manila. Demonstrators passed it on their way to picket the old Caltex offices on Padre Faura, a favorite rally venue. Another time, students held a big rally along Taft or somewhere nearby and were being chased and rounded up by policemen. My grandmother just left the front door open to give protesters refuge, and many went in and stayed till late at night to avoid arrest. She fed them and had them taken home by car, batch by batch.

In its form at that time, as source of information and entertainment produced independently by commercial stations, television provided Filipinos with a shared experience, a shared reality, although a reality experienced mostly by middle class, urban Filipinos.

Nineteen seventy-two changed all that. For our family, it meant moving out of Manila to the far suburbs into the big house my grandparents had built, and being away from the center of everything. My grandfather did not live to see that house completed; he passed away the year before. In conversations among themselves, his children would say his death was a blessing in disguise because martial law would have surely cost him his job. Even if he managed to hang on, it was unlikely he would have lasted since he was not the kind to allow a despot to run roughshod over people’s legal rights.

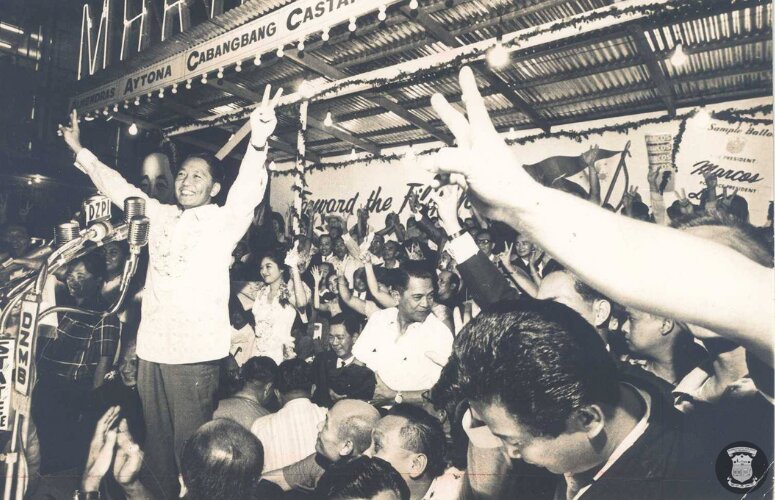

Meanwhile, Ferdinand Marcos took advantage of student unrest and used it to grab power for himself. He imposed martial law and staged a coup d’etat on his own government, deleting freedom and democracy from the Filipinos’ vocabulary. He ordered the arrest, detention, torture and execution of thousands of Filipinos. Livelihoods were snatched, companies shuttered. Nineteen seventy-two also meant the closure of commercial broadcast stations and newspapers. Marcos took over the big broadcast companies and handed them over to his cronies. Philippine television would never be the same. Martial law stunted the growth of the broadcast industry which became part of the state-sponsored apparatus of disinformation.

That year also saw the closure of Filipino-owned businesses like Radiowealth, a local company that supplied Filipinos with locally made TV sets. News accounts about what happened to Radiowealth say Marcos developed an interest in the company and wanted it for himself, forcing the owners out of business and out of the country. If not for martial law, television ownership would have spread to the rest of the country earlier and would have become a source of information and ideas from all over the world. What actually happened was that TV set ownership remained limited to the urban population, and only 20 years later in the 1990s would most Filipinos enjoy owning one. There’s an image of children during the martial law years peering through their neighbors’ window trying to watch television because they didn’t have their own—blame that on Ferdinand Marcos.

Nineteen seventy-two also meant the closure of commercial broadcast stations and newspapers. Marcos took over the big broadcast companies and handed them over to his cronies. Philippine television would never be the same.

The effects of Marcos’ declaration of martial law in September 1972 crept up on the nation, altering Filipinos and Philippine society in imperceptible ways. I have been trying to put a finger on it, and I could only come up with this: Whether known or unknown to Filipinos, martial law crushed their spirit, stole their love for life, made them fearful and distrustful, widened disparities among socio-economic classes, and most of all, deprived generations of Filipinos of knowledge and information, and real, honest-to-goodness progress.