In Hong Kong, a new generation of Filipino scientists charts their own path

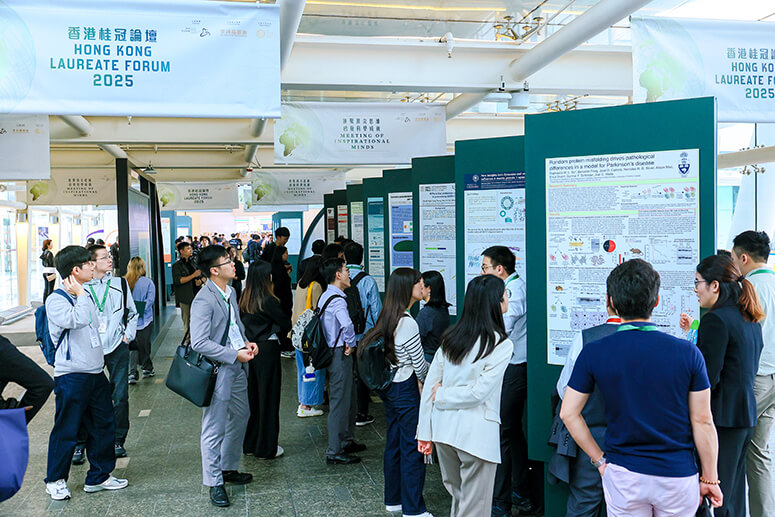

Like most Filipinos overseas, one of the first things we did during the annual Hong Kong Laureate Forum was look for kababayans. Over 200 young scientists from around the world filled the Hong Kong Science & Technology Park that week in November, so we figured it was only a matter of time.

The forum, only in its second year, was designed to bring together renowned scientists with a new generation of innovators. Invited scientists are previous winners of the prestigious Shaw Prize, awarded to individuals who have achieved distinguished and significant advances in the disciplines of astronomy, life science and medicine, and mathematical sciences.

“To have successful people (in the future), you need to have younger people who will be coming up,” said Timothy Tong Wai-cheung, professor and chairman of the Council of the Hong Kong Laureate Forum. Contrary to most conferences, plenty of opportunities were given to attendees to network, directly ask questions, and even share dinner tables with the 12 esteemed guests, including the Nobel Peace Prize winner Professor Reinhard Genzel.

Attendees varied from undergraduate students to postdocs pursuing further research. Also part of the four-day program was a dialogue between the laureates and secondary school students, who shared research of their own and toured the guests around the campus science lab. In the session, the laureates imparted sobering advice. “Problems appear more difficult than they really are,” said Professor Steven Balbus, awarded the Shaw Prize in Astronomy in 2013. “Educate yourself broadly,” added Professor John Peacock, winner of the same prize in 2014.

And Filipino attendees were indeed found: one approached us himself, while another asked a question during a Q&A with what we were certain was a Filipino accent. Below, the four young scientists we met share their stories that, while different, are all rooted in using science for social good.

‘That’s the goal of science: To make people understand’

Studying in Hong Kong wasn’t in Dr. Sheena Garcia’s original plans. “I’m from Pampanga, the culinary capital of the Philippines,” she smiled. “I only went to Manila for college.”

Before earning her undergrad degree, she attended a weeklong summer camp by the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. “They will fund your flights and accommodation for one week,” Dr. Garcia recalled. “They will show the labs available in HKUST (and you can) meet with professors and network. I met my current supervisor, Professor King Lun Yeung.” Dr. Yeung, she said, also grew up in the Philippines and finished his undergrad at De La Salle University.

During the summer camp, the professor, in casual conversation, asked Dr. Garcia how she was liking Hong Kong and what her ranking in class was. She revealed it was her first trip abroad. “The state-of-the-art equipment here may not be present in universities in the Philippines,” she remembered thinking. “I thought that if I could do my research here, I could (be) more productive.” That was when she was offered to join Dr. Leung’s research group.

She studied under the Hong Kong PhD Fellowship Scheme, where she went directly to earning her PhD. Now, at only 29, she’s a postdoctoral fellow studying nanoparticle toxicology with HKUST’s Chemical and Biological Engineering Department. Before our chat, Dr. Garcia gave a flash presentation on her research.

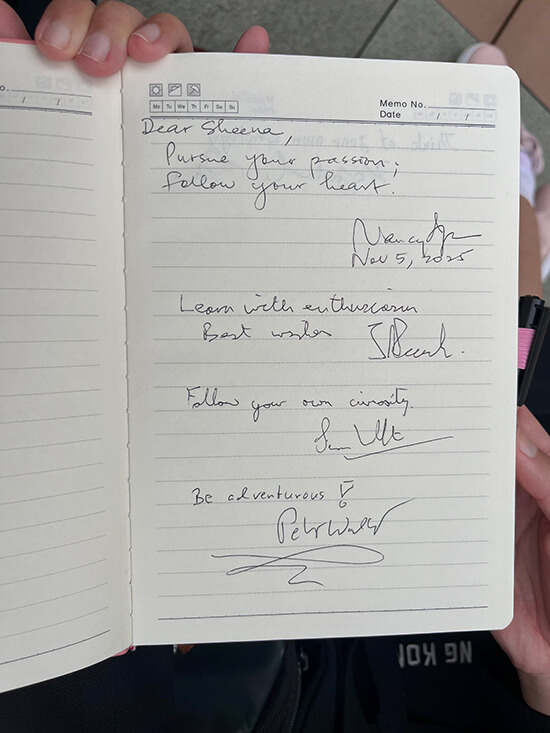

She said it was such a “rare opportunity” to interact so closely with the Shaw Laureates during the forum, even getting to ask them more personal questions. “A while ago, we were with Professor (Simon) White”—awarded the Shaw Prize in Astronomy in 2017—“and he told me that, ‘I still have weekends during my postdoc.’ He goes to the mountains. I was like, ‘Wow, it’s very good to hear that.’”

“It’s very cool how these people, these giants of their field with so much achievement, could still interact with us casually.” She also lauded the fact that the forum had no application fee, with flights and accommodations covered for attendees outside Hong Kong.

Among the Shaw Laureates, the closest to Dr. Garcia’s work was Professor Peter Walter, awarded the prize in Life Science and Medicine in 2014. “In his presentations, I appreciated how he wanted the audience to understand what he was saying,” she said. (Notably, the professor also credited his team for every specific finding by putting their names and photos in almost every slide of his presentation.) “I was inspired. I just don’t want to present my (work) and then afterwards, no one actually understood. That’s the main goal of science: to make other people understand.”

‘Science is not apolitical; science is not unemotional’

“I am the first person from Hong Kong to be a biological anthropologist,” said Dr. Michael Rivera, a Filipino-Chinese researcher and lecturer raised in Hong Kong. Focusing on East and Southeast Asia, he aims to discover “when did we first populate this part of the world, and what have all the changes been in our biology since then?” He finds answers by studying old fossils and skeletons, while his colleagues may look at other forms of evidence like stone tools or environmental data.

Because not many people are aware of the field, Dr. Rivera is working to strengthen its presence in Hong Kong. “I love how I could combine my knowledge of science and biology with history, social sciences, and the arts to have a really interdisciplinary look at what makes us human,” he explained. “As long as I keep trying to teach courses about this or talk about this with other people, most of the time, public audiences hunger for that knowledge.”

“The function of my discipline,” he added, “is to tell stories and to figure out what our common humanity and our common heritage are.” His family didn’t quite understand the field, but he was more driven by his responsibility to society. “When I think about who I do this for, it’s mainly for my students. What I find very exciting is that all of them want to save the world. They want to tackle climate change, social inequality, or food insecurity. So I hope that I'm giving them the capacities and the skills to pursue their dreams.”

Being in the field for 15 years, what Dr. Rivera deems his greatest achievement is getting to bring his students—around 1,200 of them so far—to his bone lab at the University of Hong Kong, where he manages 370 skeletal individuals. The students respond in different ways: curiosity, excitement to learn, fear, or anxiety. Bones of the elderly may sometimes remind students of people they have lost; if the skeleton has a similar age or sex as them, he said, “it’s almost like you’re looking at yourself, your best friend, or your sister.”

Dr. Rivera is proud of the fact that he not only discusses the scientific dimension, but also works with students through their emotions. “We need safe spaces in society to confront death and to talk about health and disease. And if we have those difficult emotions, I hope that more scientists will allow students to feel supported in exploring those themes.”

A large part of his work is also teaching that ethics, an oft-talked-about topic in his field, is culturally dependent. “Respect is culturally constructed,” he began. “So respect could mean, don't take photos of or tell jokes about the dead, and don't share photos of their remains on social media. But I've actually seen this happen in the Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand… Why? It's because it's their way of showing respect.”

“I'm glad that I can teach my students different cultural understanding and to think more ethically and emotionally. Science is not apolitical; science is not unemotional. I think it makes us better scientists to really embrace that fully.”

Finally, he wished that more Asian scientists would enter the field. “My field in particular has a long history of perpetuating a lot of inequalities in academic knowledge production. Anthropology and archaeology are part of the colonial mission, and the European and American powers hired lots of scientists and anthropologists to help colonial governments justify why claiming land, committing genocide and enslaving people is the right thing to do. They tried to find biological markers of inferiority, and that would help them to rule over other places,” he explained.

Asian scientists, Dr. Rivera said, “already curate the material in museums. We are already trying our best to do the science. We just need some recognition, and we just need some support.”

‘The support here is different’

Like Dr. Garcia, Ayisha Ong was captivated by the Shaw Laureates in attendance. “Roger Walter is the co-author of one of my textbooks,” she excitedly told us. The 20-year-old, originally from Binondo, is currently an undergrad student at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

After graduating from high school, Ong was considering Ateneo or UP. She ended up going to PolyU “mostly for its generosity.” PolyU is one of eight universities in Hong Kong that are fully funded by the government. “For one year of study, local students pay much less than one semester at Ateneo. For international students, (you can get scholarships) if you maintain a good GPA. My friends at the university have 100% scholarships. I myself have a stipend for living here as well.”

“I love the Philippines,” she said, “but you can’t get opportunities for internships, research, or networking like this.” Most of her friends who are also in science are considering staying for residency, despite being homesick. “The support here is different… if one of us wants to go do research in another country, PolyU will help us fund it. In the Philippines, it’s more difficult to get funding and try new things.”

Right now, Ong is doing research on bioinformatics, where she uses computer technology to study different aspects of biology. While returning home for good is not part of her future plans, she’s flying back early next year to do a service project funded by her university. “We’re doing a programming workshop for kids in Krus na Ligas High School,” she said. “The Philippines is the place that nurtured me; it’s the place I grew up in. I can always do more to help.”

‘Any map that we produce can potentially save a life’

Gelo Velasco only got to fully attend the first day of the four-day forum; it was a week of continuous typhoons back in the Philippines, and as a project technical specialist at the Philippine Space Agency, his services were urgently needed.

Under the Space Data Mobilization and Applications Division, he uses satellite data to produce maps for affected areas of floods, landslides, grass fires, and earthquakes. The division partners with local government units and different agencies, from the Department of Energy to the Department of Public Works and Highways.

In 2015, when Velasco was entering college, there was no university in the Philippines yet offering astronautics or aerospace studies, or an established government agency for space exploration. He instead studied aviation information technology at the Philippine State College of Aeronautics. It was only four years later, thanks to the PhilSA Bill principally authored by Sen. Bam Aquino, that PhilSA transitioned from being a program under the Department of Science and Technology to an agency itself.

By 2023, Velasco was one of PhilSA’s Ad Astra Scholars, where he was given the opportunity to study his master’s of science in Satellite Data for Sustainable Development at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland. He had been working with PhilSA for the past year and a half.

It had been a busy few days for him then, with two consecutive typhoons hitting the country. “The information is time-sensitive. As soon as the satellite data goes down, you have to process it immediately, so you can inform the LGUs or other government agencies,” he said. “Any map that we produce can potentially save a life.”

While the maps vary per natural disaster, two maps are projected to be produced when a typhoon hits: a flood map and a flood damage assessment. “If there are structures that collapsed, satellite data can identify which buildings these are without going directly to the ground,” Velasco explained. He recalled a story from before he joined PhilSA, where satellite data, by revealing heavily flooded areas, helped an affected family find a safer place to evacuate.

Despite missing most of the conference, Velasco said attending the first day already “meant so much.” He cited one of the responses by astronomer Professor Matthew Bailes during a panel discussion: “There were times when I didn’t do stuff for a week, then I did heavy work in a couple of days. I think that’s passion: learning to enjoy every bit of it, not burning yourself out even when it’s not making sense anymore. You don’t always love it, but you still do it because it’s your passion.”

“D’on ko na-realize na I am listening to the right person, in the right field, in the right direction,” he said. “I hope the Philippine government will inform the public (about these conferences) kasi dito tayo nakaka-meet ng mga tao na nakaka-inspire. Let’s not take opportunities away from Filipinos na kailangan lang ng information, funding or support to attend, kasi ‘yun lang ‘yung nagiging barrier; skills-wise, they have it. If that can be resolved, then I believe more young Filipino professionals can compete globally.”